Doctors, Engineers Team Up to Fight Cancer

$9 million NIH grant founds BU-based center

Imagine a world where a simple mouth swab could predict lung cancer, a blood test could warn of a recurrence of melanoma, and a rectal scan could tell if you would benefit from a colonoscopy.

That world is the vision of the Center for Future Technologies in Cancer Care (FTCC), founded here in July with help from a five-year, $9 million grant from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) at the National Institutes of Health. The center will foster collaboration among doctors, engineers, and public health and business professionals at BU and elsewhere who hope to develop technology to diagnose, screen, and treat a variety of cancers faster, cheaper, and better than is done now.

BU is one of three recipients, with Harvard and Johns Hopkins University, of a U54 award, given by NIBIB’s Point-of-Care Technologies Research Network (POCTRN).

Catherine Klapperich, a College of Engineering associate professor of biomedical engineering and of mechanical engineering and the FTCC director, says this isn’t the first time that BU engineers and clinicians have collaborated to tackle major health problems. The FTCC effort is unique, however, in its focus on cancer care. The new center will draw expertise from programs like the W. H. Coulter Translational Partnership Program and the Boston University/Fraunhofer Alliance for Medical Devices, Instrumentation and Diagnostics and will try to develop and commercialize promising prototypes.

“Cathie understands that cancer is not a high- or middle-income country problem; it’s a global problem,” says Jonathon Simon, director of the Center for Global Health & Development and the School of Public Health Robert A. Knox Professor. “With the increasing longevity of populations in low- and middle-income countries and our ability to manage the infectious disease and maternal mortality burdens, there’s just a lot more cancer that comes about because of the age structure of populations, but also because the competing risks on what else is getting people have been diminished.”

The center’s first five seed projects focus on lung, colon, skin, and liver cancers. Avrum Spira (ENG’02), a School of Medicine professor of medicine, pathology, and bioinformatics and a pulmonologist at Boston Medical Center (BMC), has found a way to detect lung cancer at an earlier and therefore far more treatable stage than it is usually found, by studying changes in cells in the windpipes of smokers. With help from the FTCC, he hopes to develop a blood test or mouth or nose swab that could reveal a high risk of lung cancer.

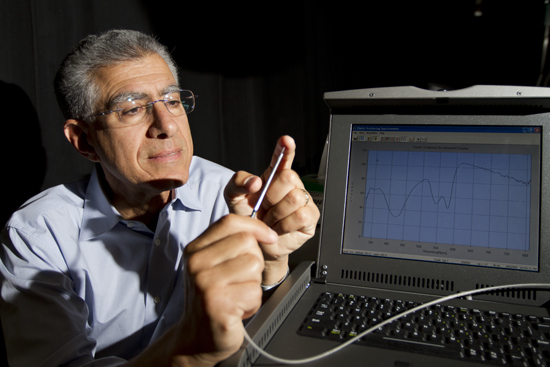

Irving Bigio, an ENG professor of biomedical engineering and of electrical and computer engineering, and Satish Singh, a MED assistant professor of medicine and a BMC gastroenterologist, have teamed up to develop a prescreening tool for colon cancer, the second leading cause of death by cancer in the United States.

Doctors recommend that everyone age 50 and over have a colonoscopy at least once every 10 years, yet compliance is low, Bigio and Singh say, because people dislike the invasive nature of the procedure. Singh notes that only half of those people who undergo a colonoscopy actually have intestinal polyps, and half of those have precancerous polyps. With this in mind, Bigio developed a fiber-optic probe that uses light and a spectrometer to detect potentially cancerous polyps, and thus signal a real need for a colonoscopy. FTCC funding will advance their research, and if it’s successful, help develop a prototype that is disposable and affordable.

Klapperich herself is working with San Francisco–based Wave 80 Biosciences to develop a blood test to detect liver cancer. The researchers are designing a cartridge that would separate the nucleic acid RNA from blood or plasma samples and use isolated nucleic acid to flag liver cancer, which kills more than 20,500 yearly in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society.

Rhoda Alani, MED’s Herbert Mescon Professor and Chair of dermatology, chief of BMC’s department of dermatology, and one of four NIBIB co–principal investigators, hopes to develop a similar technology with colleagues from the University of Texas at Austin that will analyze RNA within patients’ blood samples to determine the likelihood of a recurrence of melanoma, an aggressive form of skin cancer discovered yearly in more than 76,000 people in the United States, according to American Cancer Society figures.

The center’s fifth seed project, a collaboration between MIT and Michigan State University called My LifeCloud, is a cell phone–based system aimed at empowering patients at risk for colorectal cancer—particularly the African American population, which the American Cancer Society says has the highest incidence of, and mortality rate from, colorectal cancer of all racial groups in the United States.

Over the five-year NIBIB grant period, Klapperich says the center will encourage several new proposals, weed out a few, and provide funding for an annual summer innovation fellowship to transition lab research to a working prototype.

The grant will also allow another NIBIB co–principal investigator, Bennett Goldberg, a CAS professor of physics, an ENG professor of biomedical engineering, and director of the Center for Nanoscience and Nanobiotechnology, to lead training workshops and informal meetings at BU and around the country for students, clinicians, and faculty interested in an interdisciplinary approach to tackling cancer.

The other two NIBIB co–principal investigators are David Seldin, a MED professor of medicine and microbiology and BMC’s chief of hematology-oncology, and Arthur Rosenthal, an ENG professor of the practice of biomedical engineering and former director of the Coulter Translational Partnership Program.

Franklin Huang, a fellow in the department of medical oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, will guide the public health side of the center’s pursuits, determining population needs and assessing which advances might have the greatest impact. “One criterion for screening technology,” says the CGHD’s Simon, “is that the movement forward of science should to the greatest extent possible benefit the largest numbers of people.”

Klapperich echoes Simon’s objective to do the greatest good. As engineers, she says, she and her colleagues could sit around and “impress each other with the stuff that we made,” or they could apply their expertise in ways that will do the greatest good.

This article was originally published on September 18, 2012.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.