A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life

Works of Clover Adams, socialite, society hostess, photographer

Marian (Clover) Hooper Adams on horseback, 1869. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Most people know Marian Hooper Adams, if at all, for the tragic circumstances surrounding her death. Known as Clover, Adams was the wife of historian and author Henry Adams (The Education of Henry Adams). On the morning of December 6, 1885, she committed suicide by swallowing a vial of potassium cyanide. Her grief-stricken husband, a member of one of America’s most prominent political families (he was the great-grandson of President John Adams and the grandson of President John Quincy Adams) commissioned sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to create a memorial to mark her grave in Rock Creek Park Cemetery in Washington, D.C. The shrouded cast bronze figure has become one of the most famous sculptures in America and today is the only reason many know anything about Clover Adams.

A splendid new show currently on view at the Massachusetts Historical Society, A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life: The Photographs of Clover Adams, 1883–1885, focuses on Clover Adams’ life—not her death—specifically, on her prominence as a photographer in the years before her death. The exhibition is curated by Natalie Dykstra, author of a biography of the same title (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012).

What Adams’ photographs and the accompanying letters, diaries, and text in the show reveal is a woman of great intelligence and humor. Adams was nearly 40 in 1883, when she first took up a camera, and while the show fails to explain why she was drawn to the field, it does reveal her eye for composition, her mastery of light, and her remarkable gift for making even the most formal portraits feel informal and intimate.

One of the most memorable photographs is of Henry Adams’ parents, Charles F. Adams and Abigail Brooks Adams. The exhibition notes that Clover spoke little of her in-laws during her life, and this photograph shows us how she saw them: humorless, stern, even forbidding.

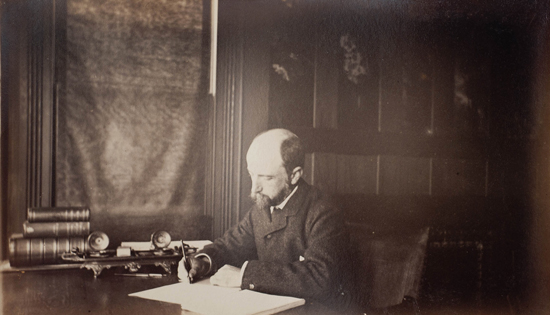

Many of Adams’ portraits were of close family friends, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., long before he became a Supreme Court justice, painter John La Farge (accompanied by a tiny watercolor of a goldfish bowl he gave Clover), and one of several women friends, Mrs. Ellerton Pratt, Mrs. George D. Howe, and Alice Pratt. But it’s a photograph of former Secretary of State William M. Evans that most reveals Adams’ skills as a technician—the portrait is rendered with subtle shades of black and gray.

The photographs reflect the serious and humorous aspects of Adams’ personality. One captures Arlington National Cemetery in all its solemnity. Another, titled “Possum, Marquis and Boojun,” is a playful depiction of her three dogs “at tea” at a table in Adams’ garden. The viewer can’t help but wonder if Adams wasn’t tweaking the social conventions thrust upon women of her staus in society.

Adams carefully assembled her photographs into three albums, and she took great pains deciding what photo would sit opposite another. The results are revealing. In two instances, images of her husband are paired with photographs of solitary trees. Dykstra notes that not once in any of the albums did Adams place a photo of herself next to one of her husband, although she was known to have taken self-portraits. In another spread, a photograph of Betsey Wilder, her father’s housekeeper, appears next to a striking portrait of her father in a horse and carriage. Adams, who lost her mother when she was five, noted that these were the two people who raised her.

She was enthralled by the latest advances in printing and developing photographs. When she began taking photos, she used albumen printing, but soon switched to a new method, the platinotype. It was an exacting process, but one she relished: in a letter to her father, she wrote that it “was science pure and simple.” Toward the end of the show, it is quietly noted that the potassium cyanide Adams killed herself with was a chemical used in the printing process.

While A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life focuses on Adams’ work as a photographer, it concludes, inevitably, with mention of her death. Just as Clover was coming into her own as a photographer, she was beset by serious depression, triggered by the death of her beloved father 10 months earlier. Ominously, her final photographs—taken on a trip to a resort in Virginia that her husband hoped would raise her spirits—bear no captions.

A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life: The Photographs of Clover Adams, 1883–1885 is on view at the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1154 Boylston St., Boston, through June 2. Phone: 617-536-1608. Hours: Monday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is free, but donations are welcome. By public transportation, take any MBTA Green Line trolley to the Auditorium stop and follow the signs to Massachusetts Avenue.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.