Detecting Explosives

ENG group’s quest to improve airport screening systems

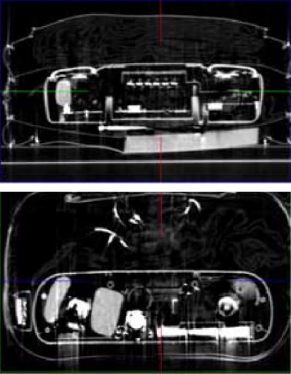

Airport luggage inspection machines scan one bag every six seconds, but the conventional medical imaging technology they use can easily overlook potential threats. In the vitally important quest to make airline travel safer since 9/11, David Castañón is working to equip these machines with a wider range of sensors and pattern recognition tools and more sophisticated signal processing algorithms to analyze the data in real time.

“We need to design a system that’s partially automated and where human intelligence gets used as needed to resolve ambiguities and produce highly reliable decisions,” says Castañón, a College of Engineering professor and chair ad interim of electrical and computer engineering. “This involves several systems engineering trade-offs: how much do you automate? What’s the algorithm you put in for making that decision? How do you generate alerts? What sensors do you bring to bear?”

Since 2008, Castañón, Clem Karl, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, Venkatesh Saligrama, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, and five PhD students have addressed these questions for potential applications ranging from whole-body imaging to video surveillance in a Department of Homeland Security initiative called Project ALERT: Awareness and Localization of Explosive Related Threats. Focusing on systems engineering solutions, Castañón is associate director and the University’s principal investigator of the project, which draws on experts from 15 academic institutions to improve the nation’s explosives detection capability.

The BU team’s effort centers on mathematical problems in machine learning, optimization, and image processing. “We model the capabilities of different sensors,” says Castañón, “develop algorithms to combine the information they gather to form decisions concerning the presence of a potential risk, and intelligently sequence sensor data to ensure that the system as a whole performs well.”

One promising solution emerging from the team’s work is an “adaptive training” system that uses video cameras to monitor pedestrian and traffic behavior, and that “learns” on the job to detect abandoned packages and vehicles by tracking changes in image pixels of sidewalks and streets. The team is also designing an intelligent sensor network system to monitor moving crowds with infrared cameras, chemical sniffers, and other devices. The system tracks individuals’ locations and detects unusual behaviors and explosives nonintrusively yet reliably.

“In explosives detection applications, most researchers focus on improving the performance of individual components, such as sharper imaging quality,” says Castañón. “We’re exploring ways of combining components and examining trade-offs to see how different data streams can complement each other to get a more accurate system.”

One important trade-off is between throughput and sensitivity. “The question of how to improve both throughput and sensitivity is at the heart of some of the novel pattern recognition and statistical learning techniques being developed at Boston University,” says Saligrama.

Mark Dwortzan can be reached at dwortzan@bu.edu.

This story originally appeared in the fall 2010 issue of Engineer.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.