All Hail, the Tuba

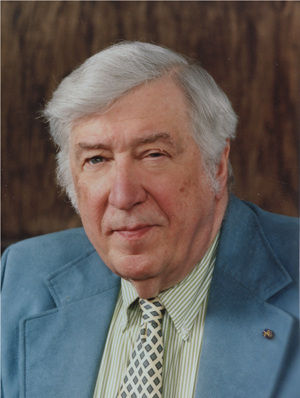

Gunther Schuller conducts BU Symphony Orchestra in world premiere tonight

It is hard to imagine a musical instrument more maligned than the tuba. Physically imposing, ungainly in appearance, sometimes lumbering in sound, the tuba has been the butt of innumerable jokes.

But tonight, the tuba gets its due. Acclaimed composer and conductor Gunther Schuller will conduct the BU Symphony Orchestra in the world premiere of his Concerto No. 2 for Tuba and Orchestra. Boston Symphony Orchestra principal tubist Mike Roylance, a College of Fine Arts lecturer in tuba and euphonium, will be featured as soloist. The performance, free and open to the public, starts at 8 p.m. at the Tsai Performance Center.

Schuller, a two-time Grammy Award winner, has been fixture on the American music scene for an astonishing 70 years. The son of a professional violinist, he began his career at 16 playing with Arturo Toscanini in the New York Philarmonic and later that year as principal horn player with the Cincinnati Symphony.

Schuller’s career is impressive not just because of its longevity, but its diversity. At age 19, he was soloist for his own Horn Concerto with the Cincinnati Symphony. He is as well versed in jazz as he is in classical music, having recorded with Miles Davis on the seminal Birth of the Cool sessions. He has written nearly 200 pieces of music, including jazz compositions (Teardrop and Jumpin’ in the Future), chamber music, and operas. But he is perhaps best known for writing pieces for instruments that are often overlooked. He’s written for the bassoon, the contrabassoon, and double bass. Now 85, Schuller has made his mark as performer, author, conductor, educator, record producer, and publisher.

School of Music director Robert Dodson, a CFA adjunct professor of music, says that the opportunity for BU students to be conducted by a composer of Schuller’s stature “will be an experience the students will not easily forget, enhancing their musical lives…as a unique learning experience and as a milestone in contemporary music history.”

“It would be almost impossible to exaggerate Gunther Schuller’s impact on music in America and around the world,” says Dodson. “He has lived in a time of great social and cultural transformation at home and abroad and has been a leader in virtually every aspect of those changes that concerned music.”

BU Today recently caught up with Schuller, who discussed the genesis of his latest work (actually his second tuba concerto), what it’s like to work with the BU Symphony Orchestra, and the future of classical music.

BU Today: How did you come to write two tuba concertos?

Schuller: I’d written one about 30, 40 years ago for Harvey Phillips, the great tuba player of our time, who just passed away a few months ago. In 2007, he called me and he said he loved my tuba concerto, and had recorded it with the New England Conservatory Orchestra. He said, “You know, Gunther, I wish there could be another tuba concerto from you.” He understood that he would not be able to play it, because he had given up playing. I had a lot of commissions. I couldn’t get to it right away. And then in 2008, I woke up one day, and I was so inspired and touched by his desire to have a tuba concerto, even if he wasn’t involved in it.

I wrote the piece in record time. It is a big, four-movement piece. I also did some things in this piece, musically, structurally, orchestrationally, and so on, that I’ve never done before. There was a very special inspiration in this piece. And because of my friendship with Harvey and my love of that instrument, all these things came together.

You’ve written quite a few concertos for instruments that don’t normally have concertos.

I have some kind of a special feeling for low register instruments. I’ve had that since my teen years. It’s interesting because, after all, music is built on the foundation of the lowest notes, what we call roots and chords and so on. So the bass of an orchestra is really, in some sense, the most important part of the whole musical structure. Most people, of course, only listen to the violin or the flute or the high melody instruments. But I’ve been fascinated by bass instruments. And it’s interesting to me that I always wanted to play the bass. I ended up being a horn player. And guess what? My son is a bass player. So there’s something genetic going on there.

How do you like working with the BU Symphony Orchestra?

I’m loving it very much. You know, I’m a very—how shall I put it—I’m a very tough conductor. Because I’m a kind of crazy perfectionist. And I don’t ever let anything go. So, I’ve been challenging the orchestra in many ways, including trying to eradicate bad habits that have crept into orchestral playing. I was really pushing the orchestra and challenging them…how to play everything and to understand why a certain note or a certain phrase is the way it is. I like to teach not just what it is, but why, from the composer’s point of view. Sometimes, when I do that with certain orchestras, there’s a tremendous resistance. They’ll say, “What do you mean? I’ve played this piece 30 times, you know. What are you saying to me?” But these musicians have been very responsive.

It’s been really wonderful.

A lot has been said about classical music’s shrinking audience. What do you think can be done to encourage the growth of that audience?

I wish I could give a happy, positive answer to that. It is not only shrinking, it has shrunk for at least 30, 40 years, to the point where in our country only about 3 percent of the population is still involved in any way in, or aware of, classical music. The other 97 percent is occupied by rock ’n’ roll and rap and hip-hop. That’s not a good balance of musical culture. And by the way, jazz is in the same endangered species category. Now having said that, I’ll say that this music is never going to become extinct. But they are in a more diminished form in our culture now than they have ever been.

Orchestras are highly troubled, you know, financially. Recordings are way down. But somehow it’s still alive and energetic. But it’s so different from 50, 60 years ago. It’s a little sad. In Europe, it isn’t like this at all. There’s much more of an equivalent balance between all these different types of music.

Gunther Schuller will conduct the BU Symphony Orchestra in the world premiere of his Concerto No. 2 for Tuba and Orchestra, featured soloist Mike Roylance, tonight, February 15, at 8 p.m. at the Tsai Performance Center, 685 Commonwealth Avenue. The concert includes performances of Joseph Haydn’s Prelude to The Creation and Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 4. The event is free and open to the public and no tickets are required. More information is available here or call 617-353-8724.

John O’Rourke can be reached at orourkej@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.