Stem Cell Injunction Has Researchers Reeling

With NIH-funded research in peril, MED scientists watch, wait

In the wake of a pivotal federal court ruling this week reversing the Obama administration’s expansion of the use of embryonic stem cells in research, scientists around the country are at the edge of their seats.

School of Medicine researchers are among those wondering how they’ll be affected by the ruling. Many U.S. scientists believe that stem cells play a crucial part in the fight against Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and a range of genetic diseases. An inability to acquire the cells, which have been cultivated from 75 existing lines, could seriously jeopardize research at BU, where the versatile cells are playing a central role in understanding diseases from cystic fibrosis to sickle cell.

With about 80 percent of its funding coming from the National Institutes of Health, BU’s Center for Regenerative Medicine (CREM) faces a major setback as a result of the ruling by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on August 23. The decision prompted the NIH to announce that it is not accepting submissions for any use of human embryonic stem cell lines for review. “All review of human embryonic stem cell lines under the NIH Guidelines is suspended,” reads a statement on the NIH website.

“The court decision is unfortunate, because it threatens to impede the progress of regenerative medicine in our country,” says Elaine Fuchs, president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research. “Stem cell therapies have the potential to treat many devastating human diseases for which we presently have no cures.”

In ruling on a suit brought by a group of plaintiffs, Chief Judge Royce Lamberth concluded that the government’s policy does not draw a clear line differentiating between destruction of embryos and the use of stem cells from embryos that have already been discarded. Some researchers fear the ruling, although preliminary, will set stem cell research back to before George W. Bush limited federally financed studies to the 21 cell lines that existed in 2001.

To make sense of the important ruling, BU Today spoke with stem cell researchers Gustavo Mostoslavsky, a MED assistant professor of medicine and microbiology and CREM codirector, and George Murphy, a MED assistant professor of hematology and oncology.

BU Today: What is your reaction to this ruling?

Mostoslavsky: This is basically outrageous. Once again they’re letting religion interfere with decisions that should be made only on scientific merit. I think it’s time for our politicians to say enough is enough. It’s going back to what we experienced in the Bush administration.

Murphy: Our major point is, regardless of what our personal beliefs are, there’s no place in science for personal beliefs. We’re trying to operate on a higher plane, where everything is the research itself. What’s most upsetting to us as scientists is that courts make decisions they’re not completely informed about. And the public is in the dark.

How is the ruling likely to affect your research?

Mostoslavsky: It imposes severe restrictions in the way we write grants. We depend on the NIH for 90 percent of our funding, and following these restrictions will dramatically affect the way we do research.

Murphy: At BU, we are the stem cell researchers. What we work on mostly are induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS), which are made from skin cells that are reprogrammed in ways that make them like embryonic stem cells. They only came into existence in 2006, and no fetal material needs to be used. Our major issue is that even though we use iPS, it’s not clear that these will be as effective, so we need to use embryonic stem cells as a control. And it’s already very difficult for us to get those embryonic stem cells—from preexisting cell lines. When you order them through the proper registry, it takes from six months to a year.

What are some of the stem cell research projects under way at BU?

Mostoslavsky: The Center for Regenerative Medicine is a consortium to advance stem cell research, for the sake of the patients, especially those at Boston Medical Center. We’re studying stem cell biology of the lungs, gut, and blood, and doing research on repairing bones and biomedical engineering of stem cells. Our federal funding now is more than $5 million.

Murphy: We’re studying genetically based diseases. We can get skin samples from patients and reprogram these cells over a month, and they’ll become iPS embryonic-like cells. But we still have to compare them, so everything we do is done in parallel with fetal cells.

If stem cells are restricted to lines culled from very few preexisting embryos, will there be enough quality cells to continue all the stem-cell research on diseases such as Parkinson’s?

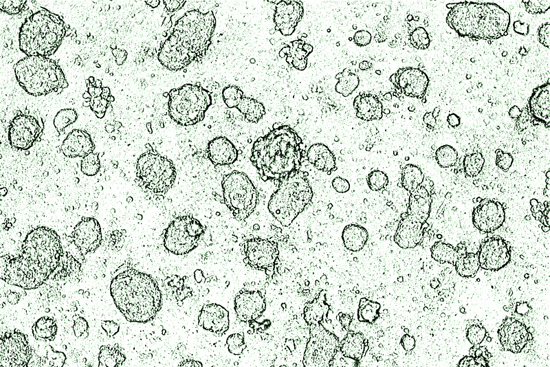

Murphy: It would be a problem. The injunction not only blocks expansion, it says original lines aren’t usable. An individual cell line comes from an individual embryo. Cells culled from that embryo are grown in Petri dishes and become an established human cell line, with all the functionality of adult tissue. Once the line is established, it can be expanded. It’s a long process, it’s immortal, and the lines are well tracked and carefully monitored.

Mostoslavsky: In the Bush administration, 21 cell lines were officially approved. But maybe five of them were usable. The rest didn’t work. Today, since Obama, there are 75 approved lines. But we have to follow whatever the NIH guidelines say today.

If this ban remains in effect, could researchers rely completely on adult stem cells or reprogrammed cells?

Murphy: It may turn out in the next few years that iPS or adult stem cells will replace the use of fetal material. But it’s far too soon; we still need embryonic stem cells. And with this injunction, not only are the preexisting lines coming to a halt, but the ruling applies even to donated embryos. Everything is off the table. As a researcher who uses and grows these lines, I know that some are contaminated, some don’t work as advertised, and in some lines people didn’t really know what they were doing. That’s why Obama expanded the number of cell lines we could use. He realized that the material we need to cure disease—where were those cells going to come from?

Does the NIH carefully monitor stem cell use?

Murphy: Obviously everyone plays by the rules because they could pull all your money, and basically your career is over. If you lose your funding you’ll never get it again.

Do you think the situation will be resolved in scientists’ favor?

Mostoslavsky: I think what happens now depends on the president, and the NIH.

Murphy: I’m pretty sure this will be resolved, but it will take a while. Meanwhile, it appears the war is on.

Susan Seligson can be reached at sueselig@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.