Playing Hardball

Tom Whalen on the early years of the Boston Red Sox

“I get a lot of hate mail,” says Tom Whalen.

One of Boston University’s most sought-after experts on Americanpolitics, the College of General Studies associate professor is frequently quoted in news outlets such as The Economist, the Washington Post, the Boston Herald, CNN, and NPR. His regular commentary on Politico,in particular, generates a range of heated reader responses. Whalen hasalso written books about politics and the personalities involved. Twoof his best known are Kennedy Versus Lodge: The 1952 Massachusetts Senate Race and A Higher Purpose: Profiles in Presidential Courage.

But Whalen isn’t only a professor of social sciences — he’s also aBoston sports fan. Several years ago he blended his love of localsports lore with his interest in social history in Dynasty’s End: Bill Russell and the 1968–69 World Champion Boston Celtics. Now he’s done it again, in an upcoming book tentatively titled Birth of a Red Sox Nation.

Sports reflects the broader culture in any period, Whalen says.“Russell once said the three main collective activities people havetaken part in throughout history are sports, politics, and religion.When you think about it, it’s true; there’s always some kind oforganized game, organized religion, and organized political system inour society.”

“Particularly in a place like Boston,” says area native Whalen. “The Red Sox, sports — it’s in our cultural DNA. We have a long,rich history.”

Cheap beer, bigotry, and fisticuffs

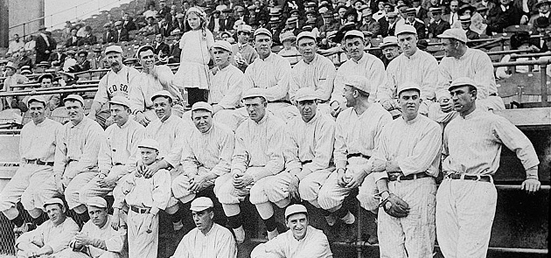

The focus of Whalen’s book is the early heyday of the Boston RedSox, who won Major League Baseball’s first-ever World Series in 1903,then four more championships between 1912 and 1918. “Outside of theYankees, no other team has won that many in so short a period,” Whalenpoints out. “That accomplishment kind of cemented the Red Sox hold onfans for generations.”

It was also a team whose very origin lay in conflict. “When the American League was founded in 1901, it wasn’tsupposed to put a team here in Boston,” Whalenexplains, per a gentlemen’s agreement.“But then the National League took steps to preemptively destroy theAmerican League, so the AL president, Ban Johnson, basically said,‘Screw them, I’m gonna put a team in Boston.’ That’s why we got the RedSox: revenge!”

The upstart Americans (as they were generally called until 1908)“stole a bunch of players from the crosstown National team, made theticket prices lower and the beer prices lower,” Whalen recounts. “Thegate attraction was there from the beginning.”

The two rival leagues soon struck a truce, settling more or lessinto today’s modern system, with a single commissioner and, of course,a World Series, by 1903. But division remained a theme in the Red Soxclubhouse, even as the team reigned on the field.

Tris Speaker, the club’s star centerfielder from 1908 to 1915, wasone of the greatest all-around players of all time, says Whalen. “Hehad the same lifetime batting average as Ted Williams and the samedefensive stats as Willie Mays. And he was a quick runner: he stole 52bases in 1912, a record that stood until Tommy Harper broke it in 1969.”

“And meanwhile,” Whalen adds, “he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.”

At that time, the KKK — led by a native of Speaker’s hometown ofHubbard, Tex. — was becoming increasingly mainstream, feeding onAmericans’ fears of a Catholic immigrant takeover. A young man then,Speaker had never met a Catholic he didn’t dislike. He made noexceptions for his own teammates. Fistfights often broke out. Speakereven brawled with manager Bill “Rough” Carrigan, “who was known as Rough for a reason,” says Whalen.

“Speaker was tight with Smoky Joe Wood, the star pitcher,” Whalensays. “They led the Protestants on the team, who were known as the‘Mason’ faction, and they didn’t get along with the Catholics on theteam, who were nicknamed ‘the Knights of Columbus.’ That includedCarrigan, Duffy Lewis, and also Babe Ruth.

“In one account I came across, a club insider said Speaker went anentire season without speaking to Duffy Lewis,” his fellow star of “TheGolden Outfield.”

That sectarian strife, he says, “completely mirrored what washappening in Boston at that time. The Brahmin establishment was beingeclipsed by Catholics, particularly the Irish, who were on the risepolitically — that’s where the Kennedys came from. In fact, JFK’sgrandfather ‘Honey Fitz’ [John F. Fitzgerald], who had become mayor bythen, threw out the first pitch at Fenway Park’s inaugural game in1912. He even tried to buy the club at one point.”

And on the paternal side of the late president’s family, saysWhalen, “JFK’s father, Joe Kennedy, played baseball at Boston LatinSchool and lettered in it at Harvard. The Irish were stronglyassociated with baseball because it was considered a way of climbing upa step in the world. And it was a major entertainment of the Irishcommunity,” typified by “‘Nuf Ced’ McGreevy, the local tavern owner,and his Royal Rooters, the Red Sox fan club.”

Curses!

Whalen chronicles the Red Sox move to Fenway Park, when the club was owned by Boston Globe publisherGeneral Charles Taylor and run by his son. “John Taylor was ascrewup,” says Whalen with a laugh. “He was like the George W. Bush ofthe family. ‘Oh yeah, let him run this baseball team.’ But he made somemoney for them when he built the park and sold the team to JosephLannin … It was a nice real estate deal.”

The new owner, Whalen argues, made the truly pivotal tradein Red Sox history, and he was behind the more notorious deal thatfollowed it. “The Tris Speaker trade was more important than the BabeRuth trade.”

Lannin traded Speaker to Cleveland in 1916 after a salary dispute.“This was the opening Babe Ruth was waiting for,” says Whalen. YoungRuth was an outstanding left-handed pitcher — he pitched 29 and two-thirds consecutive scoreless World Series innings — but “he alwaysloved to hit, and he pressured managers to put him in more games [as anoutfielder] when he wasn’t pitching,” Whalen says.

Without Speaker’s offensive firepower in the lineup, Carrigangranted Ruth his wish. By 1918, Ruth’s at-bats nearly tripled — and hisRBIs more than quadrupled. In 1919, his last season with the Sox, Ruthhit 29 home runs — unheard of in what was also the last year of the“dead-ball era,” when the spitball was legal and scores were low.

Then, Whalen contends, “Lannin inadvertently caused the Ruth trade.”He had sold the team to “the infamous Harry Frazee” in 1916, acceptingan IOU for half the sale price, Whalen explains. By 1919, Frazee stillowed $250,000 to Lannin, “and Lannin applied pressure, forced Frazee tocome up with the money. Where could Frazee go? He went to Jake Ruppert,owner of the Yankees.” Frazee sold Ruth to Ruppert for $125,000. “SoLannin was responsible for the two trades that had the biggestrepercussions for the club for generations,” according to Whalen.

Aftermath

Everybody knows the Red Sox wouldn’t win another World Series for 86years after that. However, Whalen points out, the Babe wasn’t the onlystar Boston let slip through its fingers: “The Sox had the first crackat Jackie Robinson and at Willie Mays. Imagine that: we would have wona few World Series in the ’50s!” Instead — again reflecting ethnicdivisions in the city at large — Tom Yawkey’s Red Sox were the very lastmajor league team to integrate, signing their first black player,Pumpsie Green, in 1959.

“It wasn’t the ‘Curse of the Bambino,’” says Whalen. “It was thecurse of bad management and racism that did in the Sox for so long.”

This story was originally published on the College of General Studies Web site. Read more here.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.