Picture-Perfect Children’s Reading

Children’s author-illustrator D. B. Johnson (CAS’66) inspired by Thoreau, Zinn

Among Howard Zinn’s lesser-known achievements was inspiring the creation of a talking bear that teaches children the virtues of simple living. Really.

The bear, aptly named Henry, is based on Henry David Thoreau. Zinn, the late political activist and College of Arts & Sciences professor of political science, introduced Thoreau to D. B. Johnson (CAS’66) when he was a student.

Three decades after graduating, his career as a freelance editorial cartoonist collapsing, Johnson turned to writing and illustrating children’s books. Henry Hikes to Fitchburg, published in 2000, depicted the sage of Walden with fur and paws, inhabiting Johnson’s angular, cubist-drawn world. Henry clawed his way onto the New York Times best-seller list, beginning a rave-reviewed five-book series—a string for which Johnson gives Zinn (and Thoreau, of course) credit.

Three decades after graduating, his career as a freelance editorial cartoonist collapsing, Johnson turned to writing and illustrating children’s books. Henry Hikes to Fitchburg, published in 2000, depicted the sage of Walden with fur and paws, inhabiting Johnson’s angular, cubist-drawn world. Henry clawed his way onto the New York Times best-seller list, beginning a rave-reviewed five-book series—a string for which Johnson gives Zinn (and Thoreau, of course) credit.

“I couldn’t possibly have foreseen that I was going to take my government major and be an artist and then a writer of children’s picture books,” Johnson says. “But that’s how it worked out.”

Johnson has done non-Henry books as well, including his 10th and most recent, Palazzo Inverso, based on the art of M. C. Escher (1898-1972), the Dutch artist whose woodcuts and lithographs depict geometrically impossible buildings, shapes, figures, and space. To hook young readers, Johnson apes Escher’s eye-boggling approach. Palazzo Inverso starts with text at the bottom of the pages and drawings of the young hero, Mauk, running up and down stairs and around corners to the end, when the book can be turned upside down and read back to the beginning, with text on top and a different visual take on the illustrations.

Johnson says Mauk is meant to be a young Escher (whose nickname was Mauk), “imagining an impossible world full of surprising possibilities. I want kids to feel the power and exhilaration of running on the ceiling, of knowing that everything for them is still possible.” This playful child-at-heart approach will carry over to the New Hampshire author’s next project, a book in progress about the art of surrealist painter René Magritte.

Scholars wrestle with the thinking of Thoreau, Escher, and Magritte. Rendering it comprehensible to the four-to-eight-year-old set requires Johnson first to zero in on a simple element of their work that would nab a child’s attention. In the first Henry book, that was Thoreau’s counterintuitive conceit in Walden that he could beat a train to Fitchburg on foot.

Scholars wrestle with the thinking of Thoreau, Escher, and Magritte. Rendering it comprehensible to the four-to-eight-year-old set requires Johnson first to zero in on a simple element of their work that would nab a child’s attention. In the first Henry book, that was Thoreau’s counterintuitive conceit in Walden that he could beat a train to Fitchburg on foot.

“Kids love races,” Johnson says. He made Thoreau a bear because children love animals, too, and because “you couldn’t have a woodchuck that would walk 30 miles to Fitchburg.” He simplified Walden’s language. Thoreau’s explanation for foreswearing trains—“I am wiser than that. I have learned that the swiftest traveler is he that goes afoot”—became “Walking is the fastest way to travel.”

Henry loses the race, of course. But he enjoys a glorious walk through creation’s beauty while his friend labors at his day job before hopping the train and speeding through nature without getting to savor it.

The message for kids, says Johnson, is that “getting there first and winning wasn’t necessarily the most important thing.”

A worthy message, certainly. But Johnson really hit his stride in the fourth book of the series, Henry Climbs a Mountain, based on Thoreau’s real-life jailing for withholding his taxes to protest slavery. Henry (the bear) draws a mountain on his cell wall and proceeds to climb into the picture, meeting a runaway slave at the summit who sings that freedom is on “the other side of the mountain.” They talk, and Henry gives the barefoot man his shoes. When he returns to his cell to find that a friend has paid his taxes, the jailer asks what it feels like to be free.

Henry’s simple answer: “It feels like being on top of a very tall mountain!”

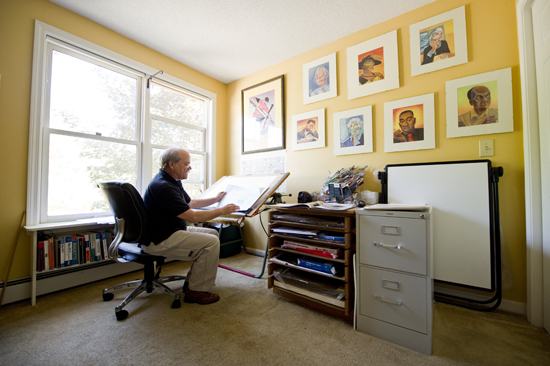

Confounding what you might expect of a Thoreau fan, Johnson lives not in the woods, but in a condo development, where he and his wife and sometimes collaborator, Linda Michelin, moved 18 years ago after downsizing from a house.

Living more modestly, he says, “was really what Henry David Thoreau was talking about.”

Rich Barlow can be reached at barlow@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.