Osamu Shimomura’s Serendipitous Nobel

Returning to BU, a chemist recounts a remarkable scientific journey

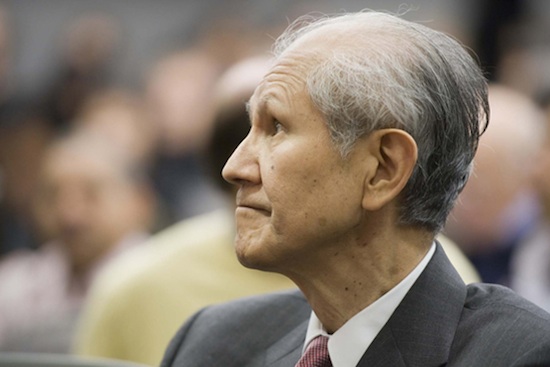

Osamu Shimomura stood quietly in front of a Medical Campus audience yesterday, slender shoulders slouched forward, eyes gazing down.

Beside him, David Atkinson, chairman of the School of Medicine physiology and biophysics department, displayed a gold medallion the size of his palm to the growing crowd: Shimomura’s Nobel Prize in chemistry.

“See that everybody?” Atkinson asked. “That’s the real thing.”

Shimomura, a MED professor emeritus of physiology and a former senior scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, was one of three winners of the prize in 2008 for his discovery of green fluorescent protein in the jellyfish Aequorea victoria. He shared the $1.4 million award with Martin Chalfie of Columbia University and Roger Y. Tsien of the University of California, San Diego, two researchers who pioneered cellular research techniques using the proteins Shimomura identified.

Shimomura was back at BU to give his Nobel Prize presentation, Discovery of Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP: My Nobel Prize Lecture, before dozens of BU faculty, staff, and students in the auditorium at 670 Albany Street.

President Robert A. Brown introduced Shimomura. Without the researcher’s discovery of “tiny molecular flashlights,” Brown said, many of the experiments performed in laboratories around the world, in fields ranging from biophysical chemistry to ecology and evolution, would not be possible.

All this from a man who saw the horrors that scientific experimentation can bring. At 16, Brown recounted, Shimomura was 15 kilometers from the epicenter of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki at the end of World War II.

“It would not be a stretch to imagine that a teenager from Nagasaki or Hiroshima might reject science because of its role in the Manhattan Project,” Brown said. “We are fortunate that Dr. Shimomura did not succumb to such thoughts.”

Shimomura took the podium, pulling out a wad of papers neatly folded in half, and began to read his Nobel lecture. His deliberate English, with its Japanese accent, mingled with the language of chemistry.

His discovery of GFP came years before his time at BU. In fact, Shimomura joked, he was not a “very good professor,” having come to the University only three times from 1982 to 2001. University officials weren’t aware he had retired until the day the Nobel Prize in chemistry was announced. They immediately moved to vote him professor emeritus.

The 81-year-old Nobel winner stumbled into chemistry studies in Japan. Few schools were left standing after the war’s destruction, and years passed before the Nagasaki College of Pharmacy opened a temporary campus near his home.

“I didn’t have any interest in pharmacy,” said Shimomura. “It was the only way that I could have some education.”

Fast forward to 1959, when Princeton invited Shimomura to join the university as a research biochemist. By then he had a doctorate in organic chemistry and acclaim for his work at Nagoya University with biofluorescent molecules.

Alongside Princeton Professor Frank Johnson, Shimomura started in 1961 to make regular summer pilgrimages to Friday Harbor Laboratories at the University of Washington. Their job was to extract the bioluminescent substance from the Aequorea victoria jellyfish abundant in the region.

It was only after some soul-searching in a rowboat, and a little luck in the lab, that Shimomura discovered how to extract two proteins from the jellyfish rings. The first protein glows blue when exposed to calcium; the second, GFP, produces a green light when exposed to the first.

Shimomura held up a test tube filled with green liquid. He flicked on a handheld ultraviolet light, and the tube glowed. “There are 20,000 jellyfish in this test tube,” he said.

Shimomura held up a test tube filled with green liquid. He flicked on a handheld ultraviolet light, and the tube glowed. “There are 20,000 jellyfish in this test tube,” he said.

Shimomura, Johnson, and their families worked tirelessly that summer, from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m., collecting and processing 50,000 jellyfish, about 2,000 to 3,000 a day. “Our laboratory looked like a factory and was filled with a jellyfish smell,” he said to a burst of laughter.

Their labor produced enough material to study the chemical structure of the two proteins, which Shimomura mapped in 1972.

Through the work of Chalfie and Tsien, Shimomura’s proteins are now used as glowing markers to follow internal biological processes, like the development of nerve cells in the brain or how cancer cells spread.

Sadly, the population of his subject jellyfish Aequorea victoria has drastically dropped in recent years — although not because of his research, he said to more laughter.

“I have not tried nor intended to discover” a glowing marker that proved so helpful to medicine, Shimomura said.

“It is a good example of showing the importance of basic research that has no practical value.”

Leslie Friday can be reached at lfriday@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.