Hanging with Bukowski at the Gotlieb Center

He’s in there, among seven miles of collections

Charles Bukowski spent a lot of his life in bars, at the track, too. Far as we know no horses are named after him, but there are a couple of watering holes around town sporting his name. He never owned them, never started a fight in one of their booths, but the mention of his name still encourages a deep thirst among some.

“Hank” as he’s known to some fans, “Buk” to others, has been a cult literary figure for decades, decorating T-shirts and bumper stickers, the epitome of hard-drinking, blunt-writing, brawling no-compromise. But what really matters are his words; his former publisher compares him to Walt Whitman, and French existentialist Albert Camus called him America’s greatest writer of the time. Hank, who died in 1994, was the street’s answer to The New Yorker and academe — the poet laureate of skid row.

So when I saw Bukowski listed among the 2,000 or so collections at the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, my eyes lit up. He was a presence for me in college, but of greater significance in sobriety. Bukowski marches fierce and poignant observations naked onto the page, propped against the abyss with only a period. I still tape his poems to my computer. One of my favorites, “Art,” is just seven words long: As the spirit wanes, the form appears.

I have it tattooed on my chest.

Now I come to find that more than 100 of his personal letters, both typewritten and handwritten, many of them illustrated with his whimsical sketches, are stored at Mugar Memorial Library. With a little notice, anyone can sit down and read them.

So I made an appointment with Ryan Hendrickson, HGARC assistant director of manuscripts. That morning, I took the steps two at a time to the fifth floor, heart pumping with anticipation — or was it exertion? After signing in and surrendering my ID, I met the young, bearded archivist, who brought me to a reading room with a couple of leather couches and six wide tables. Hendrickson locked my coat and bag in a cabinet. No cameras, no large pockets. Pencils only. “It’s policy,” he said with a firm but pleasant smile.

Hendrickson told me the Bukowski material was originally purchased by Boston-based manuscript dealer and collector Paul Richards, a good friend of the late Howard Gotlieb (Hon.’88), who began collecting the memorabilia of contemporary figures, many not yet well-known, for the University in 1963. When Richards retired, he donated his unsold stock to the HGARC.

“The letters have been used quite a bit,” Hendrickson said, “at least one person a year, maybe more, which doesn’t sound like much, but for a manuscript collection it’s actually pretty significant.”

Hendrickson left to get the material. HGARC stores most of its goodies in secure, alarmed vaults on various floors throughout the library — seven miles of linear shelf space, one reason the center staff asks for two days’ notice, in case a collection lives in a far corner or in off-library vault space.

While I waited, I strolled the room, stopping at display cases. Behind the glass, an original Alfred Tennyson poem, a handwritten letter by Edgar Allan Poe, and manuscript pages from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. The Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) collection is one of HGARC’s crown jewels, but the center has collections ranging from musician Franz Liszt to poet Robert Frost (Hon.’61) to newsman Dan Rather (Hon.’83). In this fifth-floor world, there’s not much separating you from a handwritten note by Abraham Lincoln questioning the Emancipation Proclamation, a pad scrawled with free verse by Allen Ginsberg, or the dog tags Willem Dafoe wore in Platoon. And that just scratches the surface. For students, there are some serious extra-credit points lurking in here.

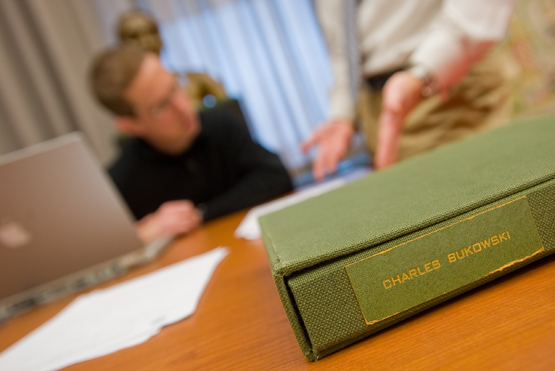

I popped my laptop at a table and within a few minutes Hendrickson returned with the goods — and a pair of white gloves, to prevent oil and dirt from compromising the pages, he explained. Then he set down a hardcover green cloth binder with Bukowski’s name printed in gold letters on the spine.

As I slipped on the cotton gloves, I felt a bit like a manservant ready to pour tea for m’lady. I wondered what Hank might have thought about such precious treatment, the poet who so beautifully and unapologetically sang the song of the diseased, the downtrodden, and the outcast — his people, himself. But I forgot all that, because in front of me was four years’ worth of letters from Bukowski to Doug Blazek, a California poet and driving force in the “mimeograph revolution,” an underground publishing movement in the 1960s that paved the way for nonestablishment poets.

Holding the first letter was, appropriately, intoxicating. Slightly wrinkled in places, smudged in others. Dried beer drops? Cigarette ash? I fought the urge to slip a finger out of my glove and run it over the imprints of the letters hammered onto the typewritten page — to transport myself to Bukowski’s desk, to touch what he touched. Hank had filled the margins with sketches: a man standing in a birdcage, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, a toilet behind him, and a dish on the floor. A giant bird stands on the outside watching. Elsewhere, he had collaged magazine cutouts. The page was alive, the Bukowski version of an illuminated manuscript. You couldn’t do this with e-mail.

Holding the first letter was, appropriately, intoxicating. Slightly wrinkled in places, smudged in others. Dried beer drops? Cigarette ash? I fought the urge to slip a finger out of my glove and run it over the imprints of the letters hammered onto the typewritten page — to transport myself to Bukowski’s desk, to touch what he touched. Hank had filled the margins with sketches: a man standing in a birdcage, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, a toilet behind him, and a dish on the floor. A giant bird stands on the outside watching. Elsewhere, he had collaged magazine cutouts. The page was alive, the Bukowski version of an illuminated manuscript. You couldn’t do this with e-mail.

Here was a struggling poet at 45 years old, still working backbreaking shifts at the U.S. Post Office (the setting for his first novel), grappling with the birth of his daughter, Marina, trying to find time to write and pick up a typewriter ribbon, all while drinking copious amounts of liquor and betting on ponies. His life was, everywhere but in front of the typewriter, a mess. On December 4, 1965, he writes: “Frances and I have split. she and the little girl are over in a place on Carlton. it costs me something, but hell, I blow every paycheck anyhow, so what’s the difference? I see the little girl every day so she’ll remember me, I am soft in the head for her, Marina …”

“God, sounds like you have an interesting window,” he writes to Blazek. “It’s important, I always type looking out the window and whatever walks by or flys by, it gets into the poem.” Looking out those windows, Bukowski managed to pen more than 60 books of poetry and prose.

His sign-offs made me cringe at my bland and rote use of “Best, Caleb.” Here are few Bukowski versions:

“Men without eyes Multiply like flies, Buk.”

“Alabaster, Buk.”

“Slug on, Buk.”

“Hold, Buk.”

And my favorite: “Grab the faucets when it feels bad or try to imagine you are a tree trunk, and hold, baby.”

I grew wistful. In handwritten correspondence, even banged out on a typewriter, you could sense the anticipation, the hope, the suspense of a conversation that took years to conduct. Today, a comparable exchange might take a week to play out online, but who wants to read a stack of printouts? At the HGARC, they house things that last, that matter, handwrought things. It is comforting to know that this piece of Bukowski will not be lost to time, or technology.

So the other night, I pulled out some paper, a pen, and began writing a letter. Just to remember how it feels. And I knew exactly how to start:

“Hey, Buk …”

Caleb Daniloff can be reached at cdanilof@bu.edu.

Click on the clip above to hear Harry Dean Stanton read "Bluebird," an excerpt from Bukowski: Born into This.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.