Zimbabwe: “One Hell of a Crisis”

BU prof reflects on the collapse of his homeland

In the nearly three decades Robert Mugabe has ruled Zimbabwe, his reputation has gone from liberation hero to brutal tyrant.

Zimbabwe’s economy is in shambles, with high unemployment and hyperinflation. Following Mugabe’s seizure of white-owned farms, agricultural production has fallen, leading to food shortages in a country once known as the region’s breadbasket.

And yet, Mugabe maintains his grip on Zimbabwe. Late last month, he was sworn in for a sixth term as president, a post he’s held since 1980, the year the country won independence from white colonial rule. He won 85 percent of the vote in a runoff election he called after refusing to concede his loss to the opposition candidate, Morgan Tsvangirai, in an election this spring.

In the weeks leading up to the June 27 vote, the opposition, and many international observers and journalists, accused Mugabe’s henchmen of violence and voter intimidation. Indeed, Tsvangirai dropped out of the race, saying he wanted to avoid further bloodshed.

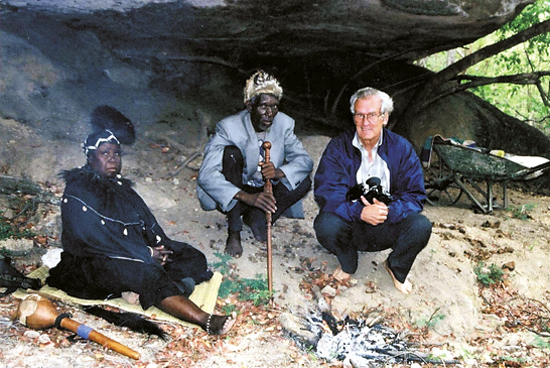

The crisis in Zimbabwe may be just now coming to a head, but it’s been decades in the making, according to Marthinus Daneel, a School of Theology professor of missiology (a mix of theology and social science), who splits his time between Boston and his native Zimbabwe. Daneel has been researching the traditional religions of Zimbabwe since the 1960s, and he has developed theological training programs for ministers of the different forms of indigenous Christianity included in his research. In recent decades, he also led efforts to link these religious groups to initiatives for positive social change, including tree planting to fight Zimbabwe’s rapid deforestation, improved maize cultivation methods for subsistence farmers, and HIV/AIDS education in a country where approximately one in five adults has the virus, according to the World Health Organization.

Daneel risks being charged with treason for criticizing Mugabe — indeed, the white colonial regime once accused Daneel of treason for refusing to take up arms against the black liberation struggle. Still, he spoke with BU Today about the crisis in his native land by phone from Pretoria, South Africa, where he is visiting family before returning to Zimbabwe next week.

BU Today: How would you describe the situation in Zimbabwe?

Daneel: Obviously we’re in one hell of a crisis. I’m talking from the rural perspective, because I move around amongst the rural people I’ve worked with for many years. They have very few medicines, such as antiretrovirals. The clinics aren’t operating properly. Our money’s worth nothing, because of out-of-control inflation.

A lot of people out in the villages are simply hungry. They’re subsistence farmers, and if they’re in the opposition party, then they don’t get enough food. Most of the commercial farms that have been given away to the so-called war vets — the cronies of Robert Mugabe — are not functioning well, and a lot of them are held by politicians who are not farmers. So you would never guess that we were once considered the breadbasket of the region.

But I know and relate to the people on the ground level, and I saw their expectations building before the first election. And then as these atrocities spread, they became even more determined and were very disappointed when Tsvangirai pulled out. They felt that the deaths had been in vain, whereas Tsvangirai thought he had to pull out to stop the killing.

These seem like problems that have been years in the making.

It was long in the making, and it should have been countered. But how do you do that if you’ve basically got one dominant party? So you end up with a dictatorship, and when you have that kind of a situation, a lot of the economy and the natural resources of the country are exploited for a privileged group and not for the population.

Is this a crisis for the entire region of southern Africa?

Yes. The silent diplomacy of South African President Thabo Mbeki is something I have really very little time for. Zimbabwe is largely dependent on South Africa for its economy. For example, Mbeki has been giving huge amounts of electricity to Mugabe at the expense of the taxpayers of South Africa. But because Mbeki is trying to cover for Mugabe, he has not criticized all the murders, torture, and killings that have taken place.

He has the power and the clout, if he wants to use them, to tell Mugabe, “These are the conditions and play ball or else we’re closing the taps.” Mugabe would be on his knees.

Are African leaders shying away from standing up to someone they regard as a fellow freedom fighter against colonial rule?

There has to come a time when you say, “Look you’re one of us, but you’re way out of line.” But right now, whenever they hear of sanctions coming from Europe or America, they throw a blanket over the African Union and say, “Keep your hands off of Africa.” Look at what has happened at the African Union meeting in Egypt — there were some African leaders who have come out and criticized Mugabe, and that’s a little better than before. But the only consensus they were able to come to was that Mugabe is still the president and needs to negotiate with Tsvangirai. And with those shallow graves of the tortured, maimed, and killed people of the opposition party lying all over the country, what kind of negotiations can there be?

Mbeki argues for a negotiated settlement in which Mugabe would agree to share power with Tsvangirai. Do you hold out hope for a power-sharing government in Zimbabwe?

I’m skeptical. I’ve seen the way things are done here, and I really doubt it will be a fair solution at all. And I think Tsvangirai has had enough. I think he will not subject himself unless there is real pressure from the outside for Mugabe to make real compromises and recognize Tsvangirai’s opposition party as a legitimate political party. Now, I’m not a politician. I’m not in the opposition. But this is probably why Mugabe acts as he has, because he realizes that the country is in the process of pretty much rejecting his leadership.

The international observers have indicated that in that first election, Tsvangirai won a clear majority, and I think it’s quite likely there will be uprisings and civil unrest until we get a real possibility of another election on even terms. The real problem with negotiating now is that the power is held by the generals, who are the same people who massacred 20,000 Zimbabweans in the early 1980s. They want desperately to retain their privileged positions and to avoid prosecution for their crimes. Thus, negotiations will fail because these generals will never give up power.

Do you believe Americans and Europeans generally don’t pay much attention to Africa unless there’s mass starvation or a bloodletting?

I do feel that there is a certain neglect, but it’s also understandable. After all, there’s no oil here, you know. That’s a cynical observation. But I’ve seen a lot of Western-backed development schemes, including ones I’ve been involved with, fall apart because of rivalries and other problems on the local level, where people get some leadership and responsibility and forget about the project itself. They want to accommodate their extended family and the clan. And they do so at the expense of the greater population that could benefit from the project. That breaks your heart time and time again. And I think this has happened so often that people in the West withdraw.

Still, Africa ultimately will have to lift itself and be counted in the world. I think that as mutual respect grows between Africa and the West, and people start to understand the continent, it will improve slowly. The love of the continent is there in so many of us, but at the same time, it’s Africa that has to help itself. It’s going to be many generations until the backlash against colonialism has healed to the extent that it’s not the fellow freedom fighter that matters. It’s the guy who’s for real freedom, instead of his own benefit, and who is prepared to build up the country and the continent. When that sensibility takes over, this country and continent will rise, I hope.

How has the current crisis affected your work?

Well, I’m down to people looking after the house, including an adopted African grandson who lives on the premises with his wife and takes care of the place. Some African staff are living there. But the teachers and others have gone. I can do follow-up research and so on. But it is also the question as to whether one wants to live with that kind of risk.

And I ask myself whether I want to continue living there, whether it’s responsible to my wife and others for me to continue living there. Can I sell the house? Maybe, maybe not. You can’t take your money out, and if you sell for Zimbabwe currency, never mind how many zillions you’re going to get for it, you can put all that money in a wheelbarrow and go throw it in a fire and then steal the wheelbarrow, because that’ll be worth more than that worthless money.

My heart says stay, and hope, and be identified with the people as I’ve done over the years. But my head says, just get out of there. I’ve lived through other violent times. I had a sister who was shot in the legs in an ambush during the liberation struggle. I was in one ambush when they hit the car of the mayor of my town, who was directly behind my vehicle. Another friend of mine, a minister, was just shot like a dog next to the road. These things did happen, and some of it can happen again when you get chaos, and then it will be too late if you’re inside.

What keeps you there?

It’s the life I’ve been living. I also don’t want to be in exile. I want to live in Africa, because I love this part of the world. My sympathy lies with the people here. They are poor, and you can pick out those who are suffering with HIV/AIDS and are on their last legs. But it’s amazing that at our ceremonies of graduation, they put on their only good clothes and they come and dance. They make an effort to come out and celebrate life. I complain about the cost of diesel and the economy and whatever, and these people who are virtually dying come out and celebrate like you can’t believe. They’ve taught me more than I have taught them about living and celebrating life while the light of day is still here. And that has been a great privilege.

The country, the continent is wonderful, beautiful. I’ve had the privilege of living here for quite a while and camping out next to that massive river, the Zambezi, where you hear at night the honking of the hippo and the lions walking and talking to each other and growling. That orchestra — it’s the continent talking to you. And if you’ve done that a number of times, it gets into your blood. It’s part of you, and you don’t want to be rid of it, because this continent sits inside you.

Chris Berdik can be reached at cberdik@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.