Research Suggests Weight Training Equals Weight Loss

Type II muscle improves metabolic health in mice

As Americans struggle with ever-expanding waistlines, the remedy suggested by friends and health experts is usually a healthier diet and more aerobic exercise. But now research by a team of Boston University scientists suggests that lifting weights may be just as important as the Stairmaster when it come to losing weight and improving health.

In experiments with genetically engineered mice, Kenneth Walsh, a School of Medicine professor of medicine, and fellow researchers have demonstrated that so-called type II muscle, the tissue created by resistance training, improves the body’s overall metabolism through chemical signals that promote fat-burning by other tissues, such as the liver. Their findings appear in this month’s issue of the journal Cell Metabolism.

“These muscle fibers have been understudied and their metabolic effects have been underappreciated,” says Walsh, whose lab at MED’s Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute focuses on how metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes negatively impact heart health. “People thought these tissues were important for picking up heavy things and not much else.”

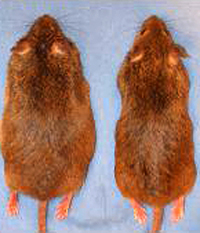

Walsh and his team genetically altered mice so that the Akt1 gene, which regulates the growth of type II muscle fibers, was turned off. For several weeks, the researchers fed the mice a high-fat, high-sugar diet, the rodent equivalent of fast food. The result, says Nathan LeBrasseur, a MED assistant professor of endocrinology: “Everybody got fat.” Really fat. The mice became obese and insulin-resistant. Fatty acid deposits formed around their livers, a condition known as hepatic steatosis, or fatty liver disease.

But then the researchers turned on the Akt1 gene in one group of mice they dubbed MyoMice. The results “were quite striking,” says LeBrasseur. Over the course of two weeks, body fat of the mice whose type II muscle fibers were allowed to grow melted away. Fat also disappeared from their livers.

The MyoMice grew physically stronger and blood tests revealed that they had again become metabolically normal. Plus, all this happened without any increase in physical activity.

Walsh speculates that the ease with which researchers can prompt rodents to do aerobic exercise may have contributed to the research neglect of type II muscle fibers. “The thing is, if you put a little wheel in a cage, the mouse will run several kilometers every night,” he says. “But I challenge you to get a mouse to lift weights.”

Fortunately, humans may be easier to convince. Walsh and his team say their findings indicate that people should consider adding resistance training to their exercise programs.

They’re hoping their next study will help identify the novel proteins, known as myokines, that the type II muscle fibers are using to communicate with other tissues involved in metabolism. These myokines could one day become therapeutic targets for the treatment of metabolic diseases. In this next round of experiments, the researchers will also manipulate the Akt1 gene in older mice, to study the impact it may have on the normal metabolic effects of aging — specifically loss of type II muscle fiber and increased body fat and metabolic dysfunction — that occur in mice as well as humans.

The researchers themselves seem to be taking their findings to heart. Walsh, for one, says he’s long been into resistance training. LeBrasseur, who once was a physical trainer, is more coy about how often he hits the weights these days. “I do my best,” he says.

Chris Berdik can be reached at cberdik@bu.edu.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.