Losing Faith and Finding It Again

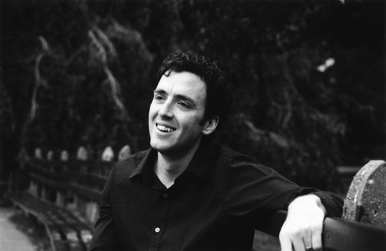

Patton Dodd (GRS’08) reads from his memoir at tonight’s Luce lecture

A one-year stint at Oral Roberts University made him question his Christian convictions, but 12 years later, memoirist Patton Dodd is keeping the faith. In his book My Faith So Far: A Story of Conversion and Confusion, Dodd (GRS’08), a doctoral candidate in religious and theological studies, explores his journey from indifferent, pot-smoking teenager to fundamentalist Christian to quizzical — yet devout — believer.

This evening, Dodd and fellow autobiographer Lauren F. Winner, author of Girl Meets God, will read from their memoirs during Writing the Spirit, an event sponsored by BU’s Luce Program in Scripture and Literary Arts. Created in 2000, the Luce Program offers undergraduate courses in Jewish and Christian scriptures, as well as in secular literatures that grow out of these traditions. It also provides specialist training for graduate students aspiring to become teachers of religion, literature, and related disciplines.

Dodd, an editor for Beliefnet, is currently writing his dissertation, on biblical literalism in contemporary American fiction. His articles have appeared in the Financial Times, Newsweek, Christianity Today, Shambhala Sun, and Books & Culture. BU Today recently spoke to Dodd about his memoir, the evangelical movement, and how his beliefs have changed since his conversion to Christianity.

BU Today: What inspired you to write My Faith So Far: A Story of Conversion and Confusion?

Dodd: Lots of great memoirs inspired me. I had never read a memoir until a few years ago, and I was struck by how much they could communicate. At their best, memoirs have a journalistic quality — they get the reader inside a culture she’d never otherwise experience. I wanted to offer that insider view of American evangelical Christianity because it’s such a curious subculture for many people.

What is the book about?

It’s about two years of my life, my freshman and sophomore years at college. It’s about a spiritual journey from a darkness laced with too much pot and beer and — more importantly — despair about my life, to an exciting religious conversion I had at a mega-church near my home in Colorado. I became a fundamentalist Christian, but it was short-lived. A year later, I was very confused about what I believed. Much of the book is about that confusion and how I tried to piece together a faith that made sense.

What drew you to the evangelical movement as a teenager?

Like most evangelicals, I was not initially drawn to the movement so much as I was drawn to the idea of Jesus. I wanted to experience the love and acceptance of God. Of course, the culture of evangelicalism helped make that possible, because evangelicals tend to be very careful about culture — the right music, the right clothes, the right tone. I’ve since gravitated toward expressions of Christianity that are dustier and more countercultural, but when I was 19, evangelicalism was a natural, comfortable environment in which to deal with ultimate questions.

What are your views toward the movement 10 years later, and why have they changed?

My views are all over the place, partly because evangelicalism itself is all over the place. Evangelicals are not the monolithic, ideologically predictable folks the media make them out to be. I admit that a certain kind of hard-core, right-wing, Bible-thumping evangelical has made a lot of noise in recent years, but I tend to think that version of evangelicalism is fading. Not that it’ll go away entirely, but if you roamed within evangelical circles, you’d find that a major rethinking project is under way. Evangelicals are reconsidering their politics, their interpretations of the Bible, their church structures, and more. I can’t predict what will happen, but I’m heartened that overhaul attempts are being made so that evangelicals can maintain their core identity as people who take Jesus seriously, but rid themselves of the baggage of political and cultural uniformity and inflexibility.

While that rethinking project is happening, I do think evangelicals are facing another major problem, which is that many of them have capitulated entirely to the culture of consumer capitalism. As long as evangelical churches will not consider how Christianity might require a resistance to the values of consumerism, they are doing themselves a great disservice.

How would you label your current faith?

Christian. I could offer a list of qualifiers, but in brief, I’m attempting to be faithful to the historical witness of the Christian faith, even as I learn what that means.

How have readers from the Christian and secular communities reacted to the book?

The reaction has been kind from both quarters. I hear from Christians who are relieved to know that someone else has struggled so much with faith, and I hear from people of other religions or no religion who say they enjoyed a readable, honest account of what it’s like to be an evangelical.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I hope people of faith will take away a sense of humor and perspective about the struggles of keeping faith. I hope people who are curious about the subculture of evangelicalism will gain an informed, human perspective. I tried to write an enjoyable page-turner, so I hope people find that they want to keep turning pages.

How has writing the book changed you?

I’m not sure I’d be a Christian today if I hadn’t written the book. I was deeply in doubt when I started writing, and the process of examining my past and making sense of it helped me to recover my faith. My faith is more critical now, but it’s also more sustainable.

Writing the Spirit: A Reading and Discussion of Spiritual Autobiography takes place at 5:30 p.m. Thursday, April 19, in Room 426-8 at the School of Management, 595 Commonwealth Ave. The event is free and open to the public. For more information, contact Cristine Hutchison-Jones at crissy@bu.edu.

Vicky Waltz can be reached at vwaltz@bu.edu.