A Conductor Reflects on the American Classics: CFA at Symphony Hall

Part two: Samuel Barber’s praise, prayer, and judgment

On Monday, December 3, the Boston University Symphony Orchestra andSymphonic Chorus will perform the first of two annual concerts atBoston’s Symphony Hall. More than 250 musicians — mostly from theCollege of Fine Arts school of music, but representing other BU schoolsand colleges as well — rehearse for weeks preparing for theperformance, which Ann Howard Jones, a CFA professor of music anddirector of choral activities, describes as an “experience that can seta standard by which all of their music-making can be measured.”

“Thegoals for the performance are to reach artistic heights that areenhanced by playing and singing in a hall where the musicians canreally hear themselves,” she says. “A young performer’s musicaleducation is not complete without excellent performance of music of thehighest possible quality.”

Monday’s concert features works by American composers, including Charles Ives’ Psalm 90, Samuel Barber’s Prayers of Kierkegaard,and Aaron Copland’s Third Symphony. David Hoose, a CFA professor ofmusic and director of orchestral activities, will conduct theorchestra, and mezzo-soprano Penelope Bitzas, a CFA associate professorof music, will be the soloist. Hoose shares his thoughts on the workswith BU Today; below, he explores Barber’s iconoclastic style and religious themes. Yesterdayhe reflected on Ives’ role in furthering the American classicaltradition in the early 20th century; check back on Monday for histhoughts on Copland’s World War II–era reflection on America.

Monday’sperformance takes place at 8 p.m. at Symphony Hall, 301 MassachusettsAve., Boston. Tickets are $35, $20, and $10 and are available at theSymphony Hall box office, 617-266-1200, and the Tsai Performance Centerbox office, 617-353-8724. For more information, click here.

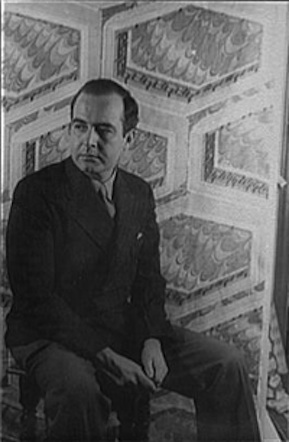

Samuel Barber’s Prayers of Kierkegaard

By David Hoose

DistinctlyAmerican, but passionately cosmopolitan, Samuel Barber found his ownpath. He rejected Arnold Schoenberg’s densely chromatic language,though he was devoted to the long-lined thought that defined Germanmusic for 150 years, including Schoenberg’s. And he rejected both thecomplexities of Charles Ives’ world (he couldn’t abide the music) andthe cool intensity of Aaron Copland’s, though the piercing rhythmicvigor of both drive much of his music. About himself, Barber wrote, “Iwrite what I feel. I’m not a self-conscious composer…. I think thatwhat’s holding composers back a great deal is that they feel they mustcreate a new style every year. This, in my case, would be hopeless…. Ijust go on doing, as they say, my thing. I believe this takes a certaincourage.”

Though his music broke no huge barriers and defined nonew language, its deep feeling communicates so powerfully that it ishard to resist. Performers find his music gratifying to sing and play,and audiences — when given the opportunity — are rewarded by hismusic’s energy, eloquence, and openness.

Barber’s compositionaloutput, however, was fairly modest — making his impact on the musicalscene all the more remarkable — and even only a limited number of thoseworks are heard. The one symphony (a second was withdrawn), one or twoof the orchestral essays, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, the one string quartet (whose slow movement became the Adagio for Strings, a piece whose commercial misuse may be matched only by the unimaginative perversions of Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man), Summer Music(for wind quintet), and a generous number of songs that are staples ofyoung singers are about all that have much currency. The ViolinConcerto, known by conservatory-aged violinists, shows up on programsonly rarely, and the Piano Concerto even more rarely. The two largeoperas, Vanessa and Antony and Cleopatra, have, on the other hand, received some attention in recent years.

Among Barber’s lesser-known compositions, however, there are gems. Music for a Scene from Shelley, the Third Essay, and Andromache’s Farewell are among them. And his Prayers of Kierkegaardis one of the most ambitious and affecting. Barber took 12 years tocompose this work after it was commissioned by the Koussevitzky MusicFoundation. Given its premiere on December 3, 1954, by the BostonSymphony Orchestra, the Cecilia Society Chorus, and Leontyne Price (forwhom it was written), with Charles Munch conducting — and its New Yorkpremiere four days later, sung by the Schola Cantorum — it was receivedwith great eagerness and enthusiasm. Like much of his other music, thisextended single movement, multisectioned cantata for chorus, largeorchestra, soprano solo, and incidental contralto and tenor solos,integrates a carefully wrought lyrical line (the consistentcharacteristic of his music that ties him to the European tradition), avivid rhythmic sense (the American thought), evocative harmony (bothEuropean and American), and a creative sensitivity to the performingforces at hand.

For this cantata, Barber chose, adapted, andrearranged prayers and a sermon of Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), thephilosopher, theologian, and harsh critic of vacant formalities of theDanish church. Kierkegaard’s theological and philosophical writings areoften intentionally complex and abstruse — he wrote that “the task mustbe made difficult, for only the difficult inspires the noble hearted” —but the words Barber selected, found in “The Unchangeableness of God”and “Christian Discourses,” communicate with remarkable incisiveness.

Barber’sfluent musical thought penetrates and unveils these very personal wordsthrough a wide variety of musical ideas. The music presents the fourprayers in one extended movement, but each prayer receives a distinctcharacter and musical treatment in support of its theologicalperspective. The first, speaking of God the unchangeable, unfolds inthe oldest of musical thought, unaccompanied chant, the type of musicthat to Barber was “the only religious music possible.” The completeprayer is offered, and the orchestra responds by quietly picking up thechant in imitative counterpoint — a younger musical process than chant.Gradually, the chorus and orchestra join and together they build untilthey surround the words “O Thou unchanging” in a swirling climax.

Thesupplicative second prayer, the only one uttered in the first personsingular, unfurls in a single voice, a soprano whose arching lineshover above a gentle rocking beneath. The third prayer begins withthick choral writing that suggests a Russian choir, and throughout itgrows only denser. Growing more and more determined, the music finallycatapults into a hedonistic orchestral dance, at the climax of whichthe chorus cries twice, “Father in Heaven!” The momentum eventuallyrelents, and from the dance’s disappearing footsteps and amidst theringing of distant and deep bells, the fourth prayer begins in awhisper. Gradually, it gathers the conviction to become a hymn whosestraightforward Protestant bearing finds company in the words that askthat we be judged by our sins.

Prayers of Kierkegaardreveals the composer’s clearest statement of his religious beliefs,Protestant thoughts that somehow find resonance in complexities of thearcane theologian’s. About Kierkegaard’s work, the composer observedthat “one finds his three basic traits of imagination, dialectic, andreligious melancholy. The truth he sought after was ‘a truth which wasa truth for me,’ one that demanded sacrifice and personal response.”There could hardly be a more personal response than this one.

Click here to read part one of the series, "Charles Ives and the break with European tradition."

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.