Evolving Attitudes, and Science, about Marijuana

Course surveys America’s pot policy through the decades

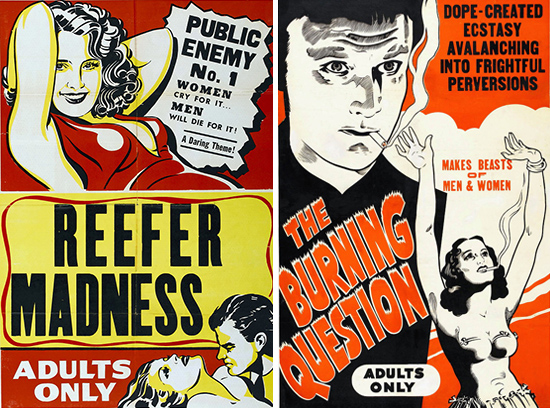

Reefer Madness (also titled A Burning Question in some prints) was a 1930s propaganda film intended to spook parents about drug use; today, it’s a pop culture punch line. Images courtesy of Chuck Coker (Flickr)

The first thing to know about Seth Blumenthal’s Marijuana in American History course is its apparent uniqueness; Blumenthal (GRS’13) says he’s trawled fruitlessly for evidence of a history-of-grass-class elsewhere, though it’s possible to find business offerings on the marijuana industry. The second thing to know: any notion that this is a fumes-shrouded pushover went up in smoke (sorry) with the summer’s first writing assignment, which required students to analyze “marijuana’s changing political and cultural significance” from the Nixon to the Reagan years.

Thus began the point of Blumenthal’s class, which he describes as “taking the giggles out” of a topic sometimes regarded as Cheech and Chong fodder. Surveying eight decades of debate over marijuana, the course argues that the contentious cannabis is a stand-in for each era’s cultural and moral anxieties.

“When people talk about it,” Blumenthal says, “they are in a lot of ways projecting a lot of their own values.”

Nowhere is that more evident than in the use, or manipulation, of science by both sides in the debate over legalization of the drug. (Two dozen states now allow medicinal marijuana, while four and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational use as well; a few allow possession but only in limited amounts.) Blumenthal recently assigned his students to collect scientific articles and determine whether they sided with the pro- or anti-legalization bench.

Pablo Rodriguez (CAS’18) said he found a 1985 Wall Street Journal article downplaying grass’s dangers, citing Vietnam vets who stopped using it with few signs of having become dependent. On the other hand, the class discussed a 1980s ad alleging the dangers of marijuana featuring David Hasselhoff (“clearly an expert,” Blumenthal deadpanned).

The government now says most marijuana users do not go on to harder drugs, backing away from its one-time “gateway drug” concern. Blumenthal outlined the recent legalization of medicinal marijuana among states for his students, beginning with California in 1996, which reframed the perception of users as stoners and hippies to focus “around sympathetic themes of health, patient rights, and compassion.”

But recent research suggests that the brain’s frontal lobes, which can judge good ideas from bad, aren’t fully mature in teenagers, making the cognitive hangover from pot use linger longer in teens than adults.

“The science we’ve seen has always changed,” Blumenthal lectured his students, “and who’s to say the science today is not being manipulated?…Research is going to keep coming out.”

In an interview, Blumenthal paraphrased some students’ initial attitude toward the class: “‘I just wanted to talk about weed and write a few papers.’” Others, however, take the topic quite seriously. J. T. Joo (CAS’16) said he signed up to better understand US attitudes, which are very different from those in his home country of South Korea.

“For my country…all drugs are bad,” he said. The class has taught him that US pot policy historically has been based on a mix of science and the manipulation thereof by both drug enforcement officials and legalization advocates. It has persuaded Joo that medical use of marijuana is appropriate. And recreational use? He scratched his chin pondering that one, then answered, “Maybe it’s OK…I don’t know for real, but some scientists say there’s no harm.”

The idea for the course originated in Blumenthal’s own student days and his dissertation on youth politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Part of his research probed Richard Nixon’s approach to spreading marijuana use, “which he called the biggest public threat in America at the time.” Nixon, elected on a law-and-order platform in 1968, found that stance an impediment in his reelection drive four years later, when arresting young tokers and imposing draconian jail terms would alienate the voters the president needed.

Nixon commendably reduced drug sentences, but in the process gave judges sentencing discretion. That opened the door to racial bias that bedevils drug justice today, Blumenthal said; federal data show that, despite comparable marijuana use rates among whites and blacks, the latter are four times likelier to be arrested for possession.

Researching all this, Blumenthal realized that the controversy over pot has always morphed in lockstep with broader social anxieties. In the Nixon era, the drug reflected the president’s grappling with the rising youth culture and vote. Today, most Americans support legalization, which they see as a blow against racial injustice; Blumenthal himself believes decriminalization is the only way to purge injustice from drug enforcement. Yet he said some libertarian advocates favor legalization for another reason: to roll back government regulation of personal behavior.

Though his class focuses on the American experience, Blumenthal also sprinkles in attitudes from other places and ages. Scrolling through a timeline on the classroom screen, he pointed out that one Chinese emperor extoled marijuana as a popular medicine in 2400 B.C.E.

Then, stumbling across an illustration, he provoked laughs by asking, “What is that—Jesus smoking marijuana?”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.