Black Classics Scholars, an Untold Story

Portraits of pioneering intellectuals on exhibit at Howard Thurman Center

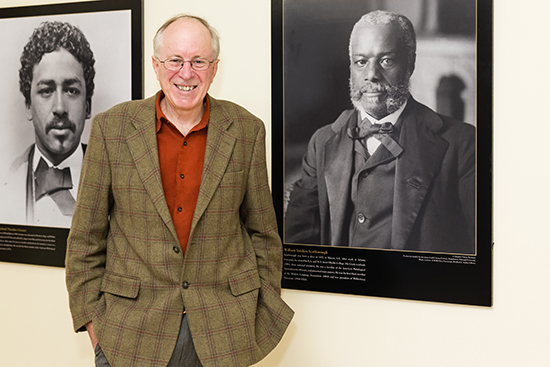

The heritage of black classics scholars has been so little studied that BU classicist Stephen Scully says he was unaware of their contributions until arranging an exhibition on the topic. Photo by Dana J. Quigley

The face in the black-and-white photo, with its wraparound graying sideburns and sober demeanor, evokes a retired Civil War general. William Sanders Scarborough couldn’t have been further from that: an African American, he was born a slave in 1852 Georgia. But he would achieve something perhaps even more extraordinary than a general’s rank.

In an era when many thought blacks unfit for higher education, Scarborough would become one of the country’s leading classicists, author of an acclaimed Greek grammar book that won him speaking engagements and an invitation to Theodore Roosevelt’s White House in the first decade of the 20th century. He wasn’t alone. As a new exhibition at the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground makes clear, Scarborough was one of several black intellectuals who became scholars of classical studies in the Gilded Age and the early 1900s.

Photo portraits of Scarborough and more than two dozen other black classicists will be on view beginning Monday, Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, and will remain up through February. The show, previously at BU’s Florence & Chafetz Hillel House, illuminates a little-known episode in the nation’s civil rights struggle.

How little known? Until he arranged for the exhibition to come here—it was first displayed at the Detroit Public Library in 2003—Stephen Scully, a College of Arts & Sciences professor and chair of classical studies, wasn’t aware that his field had been a magnet for black intellectuals a century ago.

“It’s a story that is very rarely heard, and even less imagined,” Scully says. “This is just, to me, a most inspiring story of courage. These are all pioneers.”

Their stories might have remained obscure but for Michele Valerie Ronnick (GRS’90). A Wayne State University classics professor, she was inspired to create the exhibition after stumbling upon and publishing Scarborough’s autobiography. Since its debut, the exhibition has traveled to nearly four dozen locations nationwide, mostly at universities. The BU appearance marks its first New England display, arranged after Scully met Ronnick at a summer academic confab in 2014. “I said, ‘It’s gotta come to BU,’” he recalls.

“I couldn’t be more pleased that the installation is at BU, my own alma mater, and sponsored by my own intellectual home,” the classical studies department, Ronnick says.

The appeal of classics for these early black scholars had to do with the discipline’s inclusion in what was then considered the basics of scholarly learning, which also encompassed science and mathematics, according to Scully. As is true today, he says, those African American classicists “were drawn to the intellectual and humanistic questions that one found in classics, and also just the discipline that was required to master these skills.”

These erudite topics, he says, were considered by many white Americans at the time to be beyond the capabilities of blacks, who, the argument went, were suited only to industrial training. He quotes a comment attributed to John C. Calhoun, the Southern defender of slavery who served as a senator, vice president, and secretary of state: “You show me a Negro who can parse Greek and Latin, and I will consider the possibility that he’s a human being.”

Scarborough is Scully’s favorite among the featured scholars. Born a slave in antebellum Georgia, he learned to read and write in defiance of the law. “He just adored reading” as a child, “so that when he would go out to play any one day, he would hide a book under his cloak or something,” Scully says. Scarborough went on to graduate from Oberlin College and write his grammar book, which was used in white colleges. (Scully keeps a copy in his office.)

Putting the lie to the notion that African Americans couldn’t master topics like ancient languages exhilarated black Americans, who regarded it, he says, as “a tremendous step forward in the integration of blacks into higher education and into the American intellectual discourse.” Scarborough was the first black person to join the Modern Language Association, and he became president of Wilberforce University in Ohio, the nation’s oldest historically black university.

The exhibition includes two educators who overcame the day’s racial and gender barriers. Frazelia Campbell taught Latin, German, and Spanish at her alma mater, Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth, and Helen Maria Chesnutt was a Cleveland high school Latin teacher whose students included the poet and playwright Langston Hughes.

The Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground is in the basement of the George Sherman Union, 775 Commonwealth Ave. It is open during the academic year from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday to Friday.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.