Category: Uncategorized

The Surefire Method for Writing Compelling Christmas Sermons

After graduation from Boston University School of Theology, and following close on the heels of the mid-May joyful commencement ceremony in Marsh Chapel, some students suddenly find  themselves, July 1, in a pulpit on Sunday, in meetings during the week, living in a parsonage, and wondering how to stoke the fires of a stewardship campaign.

themselves, July 1, in a pulpit on Sunday, in meetings during the week, living in a parsonage, and wondering how to stoke the fires of a stewardship campaign.

When Christmas starts to roll around, a set of specific seasonal questions may arise, one of which is about preaching. How do I preach coming to Christmas? What shall I say, or how shall I say what I say, coming to Christmas? How do I get started as I design a sermon in December?

One thought.

Coming to Christmas, you may confidently rely on the narrative and on narrative in general.

I am not generally a fan of narrative preaching, though I respect the work F. Craddock and others did to rejuvenate preaching a generation ago. But the narratives at Christmas carry well, as do stories resting upon them. There is something in the journeys at the heart of the season that calls for, or calls out, narrative.

- Some narrative is right in the Scripture—Samuel, Mary, John, Jesus.

- Some comes from the tradition (have you read Luke 2 in the KJV lately?).

- Some is reasonable, a recognition of the way our individual smaller stories fit into the one great story of the one great day of God (when you can pastorally connect someone’s personal story with an aspect of the gospel story you have given a powerful gift).

- Some is in our own experience.

Here are two examples of Marsh Chapel sermons, as a merry Christmas gift and wish, to illustrate how a narrative can function in sermons coming toward Christmas.

The first example shows how a narrative can function as a portion of a sermon.

The second example shows how narrative can be used as the design of the full sermon.

How have you used narrative in the past? How might you use it in the future? Jump in on the comments section and let me know.

The Rev. Dr. Robert Allan Hill is Dean of Marsh Chapel, Professor of New Testament and Pastoral Theology, and Chaplain to the University. Click here to peruse the Marsh Chapel sermon archive with more recent sermons available in both text and audio.

What Is the Real Task of Theological Education?

The beneficiaries of the theological education –churches and denominations – seem not to be welcoming of the transformative agents of change we call graduates.

Our attempts to offer and promulgate integrative and contextualized theolog ical education in the name of preparation may be offering an empty promise to would-be grads. Few churches or denominations want to function as seers, agents of or outposts for change. Look at the silence in the face of the “OCCUPY movement”. In fact, organized religion or mainline Christianity, in particular, seems to be under particular distress as debates rage over who/whom is not welcome into community.

ical education in the name of preparation may be offering an empty promise to would-be grads. Few churches or denominations want to function as seers, agents of or outposts for change. Look at the silence in the face of the “OCCUPY movement”. In fact, organized religion or mainline Christianity, in particular, seems to be under particular distress as debates rage over who/whom is not welcome into community.

But isn’t community all of us, diverse as we are?

Institutional challenge and social dislocation

Faith-serving institutions by their nature are often locked in by time and tradition; by custom and expectation; by the needs of survival more than the will to prosper and change in the face of moral and environmental quandaries. Institutions, particularly those charged with some aspect of faith and values, culture and tradition, by definition tend to move towards simply-stated answers or at least predictable and historical ones.

This approach may not suffice in the next decades as the paradigm of decision-making moves toward more contextually-based, responsive and situational options, and away from necessarily historic “tried-and-true” answers for all occasions.

For example, the world is challenged by unprecedented mass movements of populations due to environmental catastrophes like tsunamis, earthquakes, tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, floods, famines and droughts. These random but consequential events arising from environmental disregard have caused major re-locations of peoples on every continent. No one is spared. In the face of dislocation, one must ask what does home and community mean? This is especially pronounced when all semblances of family life and neighborhood are displaced.

Will our institutions be there for us when the whole system is in upheaval? What is our place in responding to the social chaos now? As environmental degradation creates dead places on earth and in the sea causing major shifts in populations and more particularly in the way we understand earth and sea, what is the meaning and enacting of our relationship to “our island home”, this earth?

Change is in the air

Lightning advances in the study of brain function, and technology affecting how learning takes place, what we think and why we think it, raise a number of core questions:

- What is truth?

- What is knowable?

- What is the value of knowing?

- And, how do you preach that on Sunday?

Each question offers challenge and opportunity to the decision-maker and to the faith community at-large. We are being called upon to think and react differently than our forebears, meaning that we will have to innovate, rather than repeat old stories and methods in order to emerge in a more solid place. Innovation literally means “to introduce a new way of doing something” such as “trying out new ideas”. Innovation is not anti-historical for there can be no new song without knowing something of the old song lest we be doomed to repeating a failed refrain.

Standing on a legacy of death and destruction

Remembering the Biblical evidence throughout the Judeo-Christian scriptures, prophets, apostles, and martyrs are consistently those who challenge the status quo and often fail in reformation or transformation of their religious institutions. Painfully, change is often coercive and abrupt like the threat of annihilation of the community or tradition. Exile, destruction of the sacred places, or in the case of the prophets, Jesus and the martyrs, the destruction of the person in whom change or transformation is seen is guaranteed.

Thus, with these as exemplars, the task of theological education appears to be about preparing our transforming, gifted, potentially great leaders to do change only to be smothered by the status quo of hide-bound institutions.

Innovation and faith

Futurist Rob Johansen, (see his keynote speech at the Episcopalian Diocesan Convention here) author of Leaders Make the Future, says that leadership is about innovation. Innovation is making a “meaningful improvement in well-being for the future.” He adds, innovation, itself, is about making meaning. Making meaning is the work of theology with eyes wide open, ears listening and attentive, and hearts on fire. Doing theology is how we make meaning, and the goal of theological education. Johansen continues: “faith equals a meaningful leap into uncertainty”.

It would also seem, then, that the function of faith is not just an intellectual pursuit in making meaning, but has a direct application to life. Johansen suggests that society or perhaps civilization as whole needs innovators to survive the onslaught of challenges in the immediate years ahead. As Johansen observes, faith and innovation require each other. Theological education is about the task of “faith-making” and “innovation”. Explicating their subtleties and meanings and creating an ethos which supports this activity requires focus, attention and creativity.

When seminaries turn toward the future they might be turning off churches

Noted evangelical guru, Brian McLaren, said recently that seminaries and theological schools might want to turn towards the development of new faith communities, whether they are to be called churches or something else. He adds, “The kinds of gifted, motivated, faith-filled people who are willing to invest time and money in a seminary education should be equipped, whenever possible, to form innovative and experimental new faith communities—communities which will embody the new kind of Christianity that attracts them to seminaries in the first place.” He concludes his thinking with this question, “What if, for the next couple decades anyway, seminaries became more like entrepreneurial boot camps than shop management schools?

What are we doing?

God is innovating. With us. Right now. Right here.

Thus the changes and chaos we see is part of the whole, firmly embedded in the heart and mind of God. The challenge for each of us at seminary (faculty, staff and students) is to enable ourselves to innovate. Curiously, the ancient text calls us out and reminds us, “Behold I am making all things new.” Or “I am creating a new thing.” (Revelation 21:5).

So where do you begin?

Leave a comment and let me know where you have begun, or where you hope to.

The Reverend Canon Ted Karpf, Th.M., graduated from Boston University School of Theology in 1974. He recently returned to Boston University to be Director of Development and Alumni Relations at STH and is an adjunct lecturer in Religion, Public Health and International Development. For the past seven years he was at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland and before was a missionary in Southern Africa, serving at Provincial Canon for HIV/AIDS to the Archbishop of Cape Town of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa (Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Lesotho and Mozambique). A pioneer in church and public response to HIV/AIDS with government and church since 1981, he has been a teacher of religion, a parish priest and a US Public Health Service staffer. Ted is also a canon for life in the Diocese of Washington and at Washington National Cathedral.

How to Engage Occupy as a Seminarian

A walk through the Occupy encampment in downtown Dewey Square, or a web search of the ‘Occupy’ movement reveals a myriad of voices speaking out about the current economic and social conditions of our country:

- Concerned citizens calling for greater accountability for financial institutions, corporations and government bureaucracy.

- Labor unions, employed, under-employed, and unemployed citizens calling for jobs and job security in a time of unemployment unprecedented since the Great Depression.

- A student movement calling for forgiveness of private-gain, public-risk student loans which have increased exponentially in recent years.

- Occupy the Hood and Occupy the Barrio, two movements representing the voices of communities of color, calling for a response to the poverty and violence which have plagued their communities for longer and more profoundly than any other community within the Occupy movement.

- Veterans for Peace advocating the end of America’s foreign wars, and memorializing and mourning the deaths of their loved ones.

- Pro-Palestinian activists calling for the end of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian occupied territories.

- Feminists calling for women’s rights and an end to gendered violence.

The Occupy Wall Street movement is not one homogenous movement. The diversity of voices within the Occupy movement has been formed by the diversity of lived experiences among its participants, and while the inclusion all of these voices in the movement has been a great plus, they can also cause confusion or division within the movement as it grows.

Should seminarians and faith leaders engage this seemingly disparate, chaotic Occupy movement?

Already, believers from many faith backgrounds (e.g. Christian, Jewish, Muslim and Buddhist) have shown their solidarity with the movement. The presence of a faith and spirituality tent at some rallies, as well as protest chaplains from various faith and denominational backgrounds, beckons seminarians to become involved with the movement. Among Christian groups, organizations and seminaries such as #occupychurch, Sojourners, and Union Theological Seminary, have made particularly vocal statements of support for the Occupy movement.

Whether or not we agree with the mission or the means of the Occupy movement, as leaders of faith, are we not called to respond to the contentious and significant issues of our time? This is an opportunity and challenge – not only to make ‘Occupy’ relevant to church, but for Christianity to be relevant within and for the generation of ‘Occupy.’

Here are a few ways we can engage ‘Occupy’ as part of a theological community.

Educate Yourself

If you are in seminary or graduate school, you’re likely already generally informed about many of the social and economic issues of our country today. But truly knowing and understanding the issues is different from being informed by the scholarly articles, news articles, and blogs which so often fill the life of a graduate student. To truly understand the movement means to stand beside those involved with and impacted by the movement, and to listen to them and to engage them in dialogue.

So if you haven’t already had a chance to go down to one of the ‘Occupy’ protests or encampments, I encourage you to do so.

You don’t have to hold a sign at first – or ever. Simply engage in the practice of active listening, ask participants about their involvement, and dialogue with others who are for or against the movement. Where do their critiques and/or supports come from – a logical or emotional stance?

If they are coming from a place of logic, research their data.

If they are coming from a place of emotion, don’t cast their argument aside; take into account their story and the richness that it brings. Only then can we truly understand the richness and diversity of this movement, and, ultimately, the good it may do.

Reflect on Your Own Position

It’s not enough just to educate ourselves through listening and dialogue. We also have to practice the art of personally reflecting upon each of our backgrounds, experiences and privilege, and understand how those have formed our personal understanding of the movement.

How has your privilege affected our understanding of the Occupy movement? If you’re in seminary, this likely means that you’re working towards at least your second degree in higher education. Can you truly call yourself underprivileged compared to persons who have not had the opportunity or means to pursue a graduate degree, or even a college degree?

Whether through education, class, gender, race, religious background, and/or sexuality, how have these privileges affected those outside and within the Occupy movement? How has it informed your varied and diverse understandings of the systemic oppressions which the Occupy movement is protesting? Your diverse experiences have surely contributed to your willingness to be open to and trust certain perspectives of the ‘Occupy’ movement and to discredit or reject other perspectives (particularly those that push you outside of your comfort zone).

Rather than being discouraged that we are all at times blinded by our own privilege and experience, we must lend ourselves to a practice of humility. Humility in the context of ‘Occupy’ can be enacted through a willingness and openness to learn from others who have had different experiences and perspectives than your own. We can also be hopeful that that our experiences and privilege – which at times may have contributed to our own blindness – will provide us gifts to promote the message and mission of Christ within the world.

Take Action

Life experience, education, dialogue, and reflection equip us with a critical understanding of how we might best engage the Occupy movement and use our gifts. The gifts you bring to the table are unique, as are the gifts of your congregation or faith community. Just because you’re not camping out at Dewey Square doesn’t meant that you’re not part of the movement. Dialogue and action – whether in the blogosphere, in your local university general assemblies, in classrooms, or through community activism – are all critical components of this movement.

Furthermore, as the winter weather comes and more measures are taken to ensure the ‘security’ of the Occupy encampments, the physical presence of occupiers in the downtown financial districts throughout the United States will inevitably come to an end. What happens then – in the next phase of the movement – will be critical in determining the significance and success of the movement in actualizing change.

Be Critical

If you aren’t quite sure of the movement yet, your critical voice is still valuable. Each skeptic who critiques the movement sharpens the movement by questioning its weaknesses and activating untapped imaginative possibilities.

Which issues of the Occupy movement speak to the experiences of those in your congregations, and how can you engage the questions of the Occupy movement with your congregations across lived experiences of class, race, gender, sexuality and politics? How can you make your faith relevant to a movement which has already made itself relevant to multiple experiences of faith?

For seminarians, this is a great opportunity for education and training. This will not be the last socially contentious event you will have to deal with as a leader of a community of faith, so embrace this opportunity, even if you don’t find yourself embracing every aspect of the movement itself.

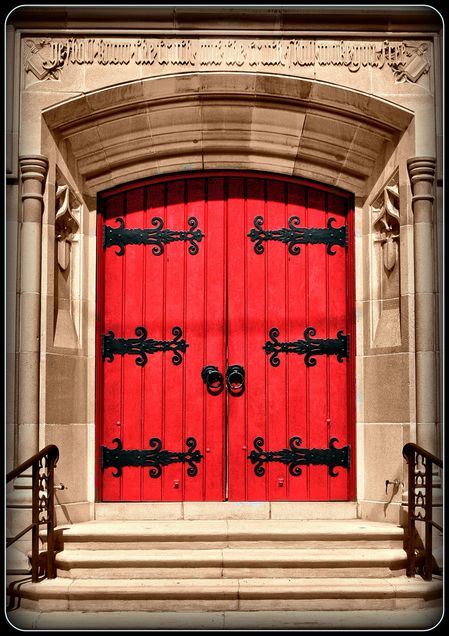

Kelly Hill is a 2nd year Master of Theological Studies student focusing in Religion and Conflict Transformation. Join the Occupy panel discussion: “The State of America: How did we get here? What can we do?” on Wednesday November 30, at 7pm in the BU Communications Building, Room 101. BU Occupies Boston will participate in a Unity March/Rally on December 3rd in collaboration with various other Occupy groups beginning at Marsh Chapel in the morning and culminating at Copley Square from 1-4pm.

How To Integrate the Pastoral and the Psychological

When I was just beginning my training at the Center for Religion and Psychotherapy, one our professors shared his experience sitting with a new client.

As he listened to the many difficulties the man was experiencing, and feeling overwhelmed, he said “you really need to see a therapist!”

Even though he was a pastoral psychotherapist, was sitting in the therapist’s chair, and would receive payment for the work he was doing, he hadn’t yet developed an identity he could claim as his own. He hadn’t developed an identity that let him be a psychologist and a pastor, which would let him provide the pastoral counseling that would benefit those who came to him.

Students and consultants often ask me how to develop such a professional identity. In this article and the two to follow, I’ll explain the three aspects of becoming what you are trained to practice:

- Claiming the influence of your faith/religious tradition

- Recognizing that pastoral psychotherapy involves integrating multiple languages of practice: theological, psychological, clinical

- Life long professional development and involvement

In this article we’ll discuss number 1, because you can’t move on to step 2 or 3 without it.

Know your Tradition

The “pastoral” in pastoral psychotherapy or counseling has to mean something to you. It might mean something related to call or it may indicate the context in which you will embody your training. But it also needs to mean something in terms of your faith or religious tradition.

So what does pastoral mean in your tradition?

If you are Christian and Methodist, what do you know about Christianity’s historical use of the term and how the Methodist denomination has understood the term? What does this history mean for you as you live into your pastoral role, whether providing care or counseling?

Or, if you are Jewish and Reformed, is “pastoral” an historically relevant term and how is it used in the Reformed movement today? Rabbi Dayle Friedman, in her edited volume, Jewish Pastoral Care: A Pratical Handbook from Traditional & Contemporary Sources, reminds us that “the term pastoral care is one that was developed in the Christian community. It has clear roots in the Hebrew scriptures . . .” And, Rabbi Charles Sheer makes this point when he says that along with what he learned in his CPE experience, his “assessment and responses are guided by sources that preceded CPE by millennia. I come from a tradition that places much stock on the written word . . .. I am accompanied by the documents of my Jewish heritage.”

Roman Catholics historically made administering the sacraments a central focus of pastoral care. What this indicates is that pastoral practitioners are in dialogue the traditions that have shaped them as pastoral leaders.

You do not leave these influences at the door of your pastoral care and counseling classes. Conversely, you must work to articulate clear statements about how they inform what, why and where you provide pastoral care and counseling. And so I ask, do you know how your tradition has informed your current understanding of “pastoral”?

Pastoral Identity Doesn’t Just Happen

We should consider, for a moment, why integrating clinical practices and pastoral identity is difficult. One reason is because it is a professional developmental task. It takes intentionality, an educational setting that takes the pastoral aspect of your work seriously, and requires that in your educational program the formational dimension is explicitly attended to as an integral part of the program. In fact, it must shape the creation of the program. So, it takes commitment from multiple parties. You, but also your educators.

If you are thinking this is not easy—you’re right! It takes a community of pastoral practitioners to help you achieve an integrated pastoral identity. But the result is one that benefits you as a practitioner and those who come seeking help from you.

For example, when someone comes to you for assistance, they are likely coming because you have “pastoral” preceding your clinical designation. For those who seek a pastoral psychotherapist or psychologist, they hope you will be able to understand the religious, spiritual, and moral impulses that frame their concerns and view of life. Not only that, they are likely coming with the hope that you know personally what it means to live an integrated life.

You don't have to present yourself as perfectly “together”

But you must convey that you value the place of religion and spirituality in a healthy life, and that in the work you do the psychological and the pastoral each contribute to your practice of pastoral care.

If the pastoral and psychological both contribute to your practice, your pastoral identity will be apparent in the following ways:

- You claim it as a part of your professional identity

- You are comfortable with a range of pastoral and religious metaphors that run through peoples’ lives

- You rely on a practice of psychological and theological reflection to help you understand your work

- Your professional colleagues will include those who also embrace a pastoral identity and work to help the broader public understand pastoral psychotherapy and psychology as important resources for individuals and communities in need of care.

None of these things will happen overnight, but you can begin the process of integrating your tradition into your practice now. Being comfortable with your religious tradition's definition of "pastoral", or its equivalent, allows you to begin integrating the the different languages of the religious and the psychological, which we'll discuss in the next part of this series.

So what does "pastoral" mean to you and your tradition? What does it mean to provide care? Jump in on the comments and let me know.

Phillis Isabella Sheppard, Associate Professof of Pastoral Psychology and Theology, is a womanist practical theologian, psychoanalyst and sometime poet. Dr. Sheppard’s research engages the intersection where the social and the intrapsychic meet. Her recently published Self, Culture and Others in Womanist Practical Theology addresses serious lacunae in pastoral theology, psychology of religion, and psychoanalytic theory.

What Can Disney Teach You About Social Justice?

Imagine the world anew. Singing birds. Flourishing forests. Little fuzzy animals to help with your quotidian tasks. A happy song to sing when you venture too far into the deep, dark forest. Faithful friends who march alongside you as you fight dragons and evil queens on the great quest for love.

Bad guys are easily defined and always defeated with surety and minimal destruction. Lovers are always reunited, friendships are restored, and broken communities are made whole. Good always wins.

Disney magic, the pure power of imagination at play, brings about happy endings for each protagonist. But Disney doesn’t live in any of the worlds it imagines.

You might even say that it perpetuates patriarchy, hetero-normative understandings of love, and just about any and every harmful ideology operating within North America.

But still …Is Disney onto something?

When I was little, I wanted to be an imagineer. Imagineers work for Disney to create theme parks, events, and entertainment venues. They are engineers, lighting technicians, scenic artists, architects, writers, sound designers, and the like. The imagineer combines her/his unique professional skill set with a big dose of imagination aiming to bring joy to the world. Their vision seeks to enhance the lives of others through the synthesis of engineering and imagination.

Sometimes, the imagineer is guided by a preconceived design scheme or an area of need within the corporation. However, much of an imagineer’s time is spent in “blue sky speculation”— they imagine what might be possible with no limitations. They have free license to dream without boundaries. They then bring their professional skills, in community, to make real their seemingly impossible visions.

So what does this all have to do with social justice?

Work for justice requires the promiscuous use of imagination; It provides you with energy to continue dreaming when previous visions have failed you.

Imagining the world to come does not mean that you are blinded to the blistered, battered Earth. You know the facts. You feel sea levels rise as island nations are swept into the oceanic abyss. You have listened hard to too many wrenching stories. You hold the hands of childless mothers. Your shoes squeak through shattered-glass-covered streets. The Earth groans and you listen to her cries.

You know intimately the pain of a world broken by systemic sin. And yet, you dedicate yourself to search for beauty where she might be found. To celebrate the glimmers of hope in every small victory. To walk in solidarity as you imagine what the world might be.

We are called to imagine the kin-dom, that ever-hoped-for land where God’s people dwell together in peace and justice. The vastness of the world’s brokenness is soul-searing. Human agency stands little chance against such forces of hopelessness.

Whether you are working as a community organizer, a legislative advocate, or a direct service worker—imaginative capacity is critical. This work demands that you hold in delicate balance a deep, embodied knowledge of injustice present in the world while allowing yourself to dream the world as it can be, to envision that great kin-dom to which you have dedicated your life.

So how does imagination empower leaders for justice?

Imagination is acting within you when you see the world as it is and dream it to be otherwise. This is not the far-off, pie-in-the-sky dreaming of denial. Rather, you imagine what might be possible and you work for it. You catch a glimpse of the long vision and eke it out in daily action.

You engage focus groups to dream of a more just public transportation system.

You think creatively about raising public consciousness.

You dream together how tenant taskforces might impact housing policy.

You create opportunities for dialogue between unlikely partners in justice work.

You change the way your own organization operates so that you mirror the ways of relating you wish to see in the wider world.

You embrace diversity and attempt to expand your creative capacity.

You lend your gifts as a visual artist, musician, songwriter, puppeteer or dancer to peace and justice.

Imagination guides us, individually and communally, as we speak truth to power in new ways. Creative energy moves through you, infusing your communities with renewed passion. The power of imagination is ignited.

Play reenergizes us for the long vision of social change.

Fight for social justice inevitably involves defeat. Many of us have been there. The program you’ve dedicated yourself to is cut from the agency’s budget. The hoped-for legislation is vetoed by the Appropriations Committee. The youth you are working with succumb to community violence. The dreams of centuries of prophets are crushed daily by political pundits whose only allegiance is to corporate pocketbooks. The week after the protest, the streets are left empty again as the world spins on. Cycles of injustice continue to be perpetuated by amorphous forces beyond our grasp.

It seems as if the glimmer of hope within you has died. And yet, if you continue to dwell eyes-downward in this landscape of crushed visions and denied dreams, your vision wanes. You become callous to the beauty amidst the broken.

Imagination calls for play. Disney’s imagineers do nothing if not create conditions for play and celebration. Perhaps there’s some wisdom in this. Children thrive at play. Are adults really any different? Do we all not need to play? Is silliness and celebration of the beauty of life only for our children? Do we not have the need to engage in silliness and to celebrate life?

In my own life, at the end of several devastating days teaching the sixth grade, I felt the need to dress up, impersonate a British accent, and play make-believe with my students in our classroom. At the School of Theology, I may be known to have bubbles, a deck of cards, and Nun Bowling in my office. When all else fails I go here. Yes, there are implications of privilege in play. But no material is needed to hop or skip to work instead of walking. Simply the desire to feel one’s spirit just a bit lighter.

Celebrations allow you to see the strengths of your work, to capture the joy of minute victories. And if no victory can be found, simply celebrate that you’re still in the fight. Celebrations create sustainability within organizations and movements. If you focus all your energy on the pathology of the present, you’ll become dismayed to the point of disabled agency. Delight in your strengths, as an individual, as well as part of a community or organization.

So, what does Disney teach you about social justice?

Well, maybe nothing directly. But the vision of the imagineer, the coupling of dynamic dreaming with dedicated action to create a better world: that’s something to believe in.

What do you believe in? How can imagination empower you and your work? Jump in and let me know in the comments below.

Ashley Anderson grew up in the mountains of Colorado with daily bedtime stories straight from her mother’s imagination and is now an MDiv/MSW candidate at Boston University School of Theology. She likes organizations like this one: www.dsni.org/youth.shtml and this one www.soaw.org.

Is Black Religious Experience More Complicated than You Thought?

The first Monday of every month we'll knock on the door of an STH faculty member and sit down for an informal chat about the books they think you need to know about. Topics will range from from literature to non-fiction, theology to philosophy.

You don't have to be on campus to attend these office hours, so jump in on the comments section to ask the professor questions or to share your own insight.

Our inaugural episode of Office Hours features Dr. Anjulet Tucker, Assistant Professor of the Sociology of Religion, as she talks about Chicago Step, a musical dance subculture that offers insight about big questions regarding African-American religious experience.

In this episode Dr. Tucker explores:

- Why a new understanding of African-American religion doesn't mean the death of African-American religion

- How a secular community may also function as a religious community

- Whether different kinds of religious communites must be mutually exclusive

- How the influence of the church extends even into secular spaces

- What the "death" of the black church means for the study of African-American religious experience

- How secular spaces may help bridge religious divides

Click the link below to listen now.

(The audio will open in another window, so be sure to temporarily enable pop-ups.)