What Is the Real Task of Theological Education?

The beneficiaries of the theological education –churches and denominations – seem not to be welcoming of the transformative agents of change we call graduates.

Our attempts to offer and promulgate integrative and contextualized theolog ical education in the name of preparation may be offering an empty promise to would-be grads. Few churches or denominations want to function as seers, agents of or outposts for change. Look at the silence in the face of the “OCCUPY movement”. In fact, organized religion or mainline Christianity, in particular, seems to be under particular distress as debates rage over who/whom is not welcome into community.

ical education in the name of preparation may be offering an empty promise to would-be grads. Few churches or denominations want to function as seers, agents of or outposts for change. Look at the silence in the face of the “OCCUPY movement”. In fact, organized religion or mainline Christianity, in particular, seems to be under particular distress as debates rage over who/whom is not welcome into community.

But isn’t community all of us, diverse as we are?

Institutional challenge and social dislocation

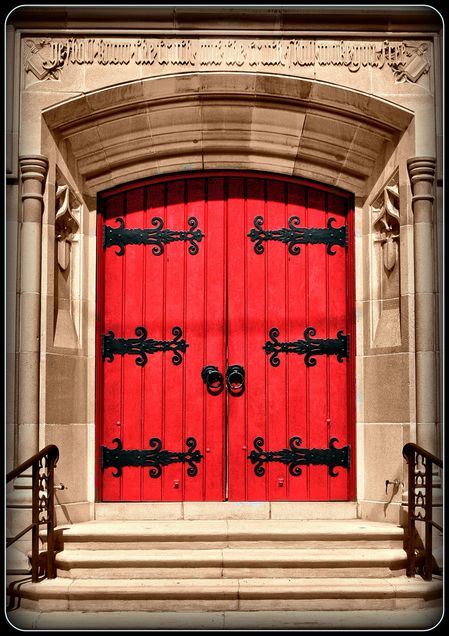

Faith-serving institutions by their nature are often locked in by time and tradition; by custom and expectation; by the needs of survival more than the will to prosper and change in the face of moral and environmental quandaries. Institutions, particularly those charged with some aspect of faith and values, culture and tradition, by definition tend to move towards simply-stated answers or at least predictable and historical ones.

This approach may not suffice in the next decades as the paradigm of decision-making moves toward more contextually-based, responsive and situational options, and away from necessarily historic “tried-and-true” answers for all occasions.

For example, the world is challenged by unprecedented mass movements of populations due to environmental catastrophes like tsunamis, earthquakes, tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, floods, famines and droughts. These random but consequential events arising from environmental disregard have caused major re-locations of peoples on every continent. No one is spared. In the face of dislocation, one must ask what does home and community mean? This is especially pronounced when all semblances of family life and neighborhood are displaced.

Will our institutions be there for us when the whole system is in upheaval? What is our place in responding to the social chaos now? As environmental degradation creates dead places on earth and in the sea causing major shifts in populations and more particularly in the way we understand earth and sea, what is the meaning and enacting of our relationship to “our island home”, this earth?

Change is in the air

Lightning advances in the study of brain function, and technology affecting how learning takes place, what we think and why we think it, raise a number of core questions:

- What is truth?

- What is knowable?

- What is the value of knowing?

- And, how do you preach that on Sunday?

Each question offers challenge and opportunity to the decision-maker and to the faith community at-large. We are being called upon to think and react differently than our forebears, meaning that we will have to innovate, rather than repeat old stories and methods in order to emerge in a more solid place. Innovation literally means “to introduce a new way of doing something” such as “trying out new ideas”. Innovation is not anti-historical for there can be no new song without knowing something of the old song lest we be doomed to repeating a failed refrain.

Standing on a legacy of death and destruction

Remembering the Biblical evidence throughout the Judeo-Christian scriptures, prophets, apostles, and martyrs are consistently those who challenge the status quo and often fail in reformation or transformation of their religious institutions. Painfully, change is often coercive and abrupt like the threat of annihilation of the community or tradition. Exile, destruction of the sacred places, or in the case of the prophets, Jesus and the martyrs, the destruction of the person in whom change or transformation is seen is guaranteed.

Thus, with these as exemplars, the task of theological education appears to be about preparing our transforming, gifted, potentially great leaders to do change only to be smothered by the status quo of hide-bound institutions.

Innovation and faith

Futurist Rob Johansen, (see his keynote speech at the Episcopalian Diocesan Convention here) author of Leaders Make the Future, says that leadership is about innovation. Innovation is making a “meaningful improvement in well-being for the future.” He adds, innovation, itself, is about making meaning. Making meaning is the work of theology with eyes wide open, ears listening and attentive, and hearts on fire. Doing theology is how we make meaning, and the goal of theological education. Johansen continues: “faith equals a meaningful leap into uncertainty”.

It would also seem, then, that the function of faith is not just an intellectual pursuit in making meaning, but has a direct application to life. Johansen suggests that society or perhaps civilization as whole needs innovators to survive the onslaught of challenges in the immediate years ahead. As Johansen observes, faith and innovation require each other. Theological education is about the task of “faith-making” and “innovation”. Explicating their subtleties and meanings and creating an ethos which supports this activity requires focus, attention and creativity.

When seminaries turn toward the future they might be turning off churches

Noted evangelical guru, Brian McLaren, said recently that seminaries and theological schools might want to turn towards the development of new faith communities, whether they are to be called churches or something else. He adds, “The kinds of gifted, motivated, faith-filled people who are willing to invest time and money in a seminary education should be equipped, whenever possible, to form innovative and experimental new faith communities—communities which will embody the new kind of Christianity that attracts them to seminaries in the first place.” He concludes his thinking with this question, “What if, for the next couple decades anyway, seminaries became more like entrepreneurial boot camps than shop management schools?

What are we doing?

God is innovating. With us. Right now. Right here.

Thus the changes and chaos we see is part of the whole, firmly embedded in the heart and mind of God. The challenge for each of us at seminary (faculty, staff and students) is to enable ourselves to innovate. Curiously, the ancient text calls us out and reminds us, “Behold I am making all things new.” Or “I am creating a new thing.” (Revelation 21:5).

So where do you begin?

Leave a comment and let me know where you have begun, or where you hope to.

The Reverend Canon Ted Karpf, Th.M., graduated from Boston University School of Theology in 1974. He recently returned to Boston University to be Director of Development and Alumni Relations at STH and is an adjunct lecturer in Religion, Public Health and International Development. For the past seven years he was at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland and before was a missionary in Southern Africa, serving at Provincial Canon for HIV/AIDS to the Archbishop of Cape Town of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa (Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Lesotho and Mozambique). A pioneer in church and public response to HIV/AIDS with government and church since 1981, he has been a teacher of religion, a parish priest and a US Public Health Service staffer. Ted is also a canon for life in the Diocese of Washington and at Washington National Cathedral.

December 22, 2011

Beautifully done! Thanks for making this argument so succinctly. One question: along with innovation, what sort of role (if any) do you see for the idea of recovery?

January 27, 2012

I wonder whether the reason the churches and denominations aren’t open to the “transformative agents of change” is because of the tone of judgment that is often expressed toward those same churches and denominations. To enter into a faith community as leader with the belief that the community’s way of faith and practice must change creates opposition from the beginning, rather than a spirit of creative possibility. It also places undo stress on the pastoral leader as the primary agent of change. What might be a compassionate approach for all involved? First, that the graduate has been formed in their theological education to deeply love the people and community to which she or he is called to serve. This forgiving, prayerful, patient, nurturing love would first model the grace of Christ to the community, before seeking to change it. Second, that the focus be centered, not on leader or congregation and on what they can or must accomplish, but on learning to join in with the redemptive love of Jesus Christ, for the sake of the world. That redemption begins in the community itself. We are called to say “no” to the powers that seek to destroy, but it is a healing “no,” a “no” that inspires and spurs each other on to love and good deeds, a “no” that realizes that we all bear in ourselves the destructive powers we condemn. Our communties’ attempts at loving may seem limited, but find those seeds and water them, and transformation will happen.