Could math change the law? What the 5th Amendment means in cryptography

The COVID-19 pandemic rapidly accelerated the digital boom. This new virtual world, though convenient, comes with issues of digital privacy and cybersecurity that the law is not yet equipped to handle. But reexamining current policies through a technical lens could provide a temporary solution.

Concepts from mathematics can help scientists, lawyers, and even governments move incrementally towards practical solutions to addressing complex societal problems, like an individual’s right to privacy in the digital age.

Mayank Varia, the Co-Director of the Center for Reliable Information Systems & Cyber Security (RISCS) at the Hariri Institute for Computing, and Sarah Scheffler, a 5th year PhD student in computer science, used mathematical proofs to better understand what information the government can compel people to produce from their phones or computers in a court of law. Their findings are detailed in a recently accepted paper for the 2021 Usenix Security Symposium.

Scheffler and Varia study cryptography — or the research and practice of secure communications using math and computer science. The duo used mathematical proofing, or systematic thought experiments, to examine the foregone conclusion doctrine in the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution as it relates to encrypted, or password protected, devices.

Normally, if a person invokes their Fifth Amendment right — the right to refuse to testify against oneself — the government can invoke the foregone conclusion doctrine to demand certain self-incriminating testimony if the testimony could already be known to the government. For example, if the government knows a person has certain tax documents, they can compel that person to produce the documents rather than going to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

But, invoking the foregone conclusion doctrine to demand encrypted information is a relatively new issue. “Compelled decryption is when a government entity, whether the court or the police, orders you to decrypt your own device,” explained Scheffler. This could involve providing the files directly, providing the device in a logged-in state, or providing the password to the device.

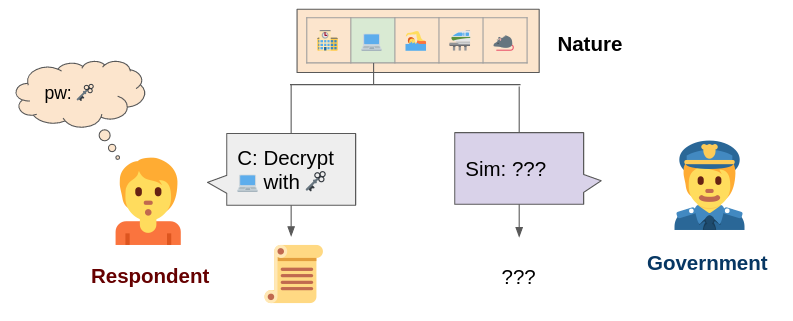

Scheffler and Varia used two different proofing techniques to test the legality of compelled decryption. What they found was that the government can demand the decryption of devices under the foregone conclusion doctrine if they’re able to obtain the information they’re requesting from someone or somewhere else. “The doctrine reasonably allows the government to compel certain kinds of testimony if that testimony is already known,” said Scheffler.

At the same time, Scheffler and Varia’s findings suggest that the government needs to provide sufficient evidence that they can obtain the information they’re requesting elsewhere. “If the government knows something, they ought to be able to simulate it,” said Scheffler.

The team is now consulting with legal experts to detail some recommendations on how the courts should apply the foregone conclusion doctrine to compelled decryption.

“Cryptography is a cool blend of applied math and societal problem-solving,” said Scheffler, “You can shine a light on difficult societal or legal problems by using a cryptographic lens.”