Money Does Grow on Trees

Save the rainforests. And a few bucks. New research is enabling companies to build sustainability strategies that don’t cost the Earth.

The national conversation about sustainability, such as it is, tends to be driven by altruistic impulses: We’ve got to conserve resources, stop polluting, and save the planet. They’re noble goals, but achieving true sustainability will require innovation, entrepreneurship, affordability, risk management, and—just as critical—the promise of financial rewards.

“Take a company like Walmart,” says Paul McManus (MBA’86), senior lecturer and a member of the New England Clean Energy Council. “It’s putting solar cells on its roofs to generate electricity that feeds its buildings. That’s a wonderful thing to do from a climate change standpoint, because it’s a clean source of energy. Is Walmart doing it because it wants to be greener? No, it is not. It’s doing it because if a hurricane like Sandy hits a store and takes it off the electrical grid for a minute, it’s losing millions of dollars of sales. Do you as an individual care if Walmart is doing this because it wants to be green? At the end of the day, it’s doing what it needs to do to stay in business. Oh, and it’s beneficial? I’ll take that. Market forces are driving behavior in the right way toward an end, and society benefits. And that’s okay.”

Across SMG—and BU—faculty are coming together to explore and build sustainability strategies that drive profit. Their multidisciplinary research covers a wide range of issues, and has the potential to be a game changer in energy efficiency, solar power, government regulations, and a variety of other areas.

“Much of our research at the School is looking at the fundamental issues of technology, science, human behavior, and social systems related to becoming a more sustainable society, and the opportunities and challenges they present for business and industry,” says McManus. “Businesses are being incredibly proactive about preparing themselves for business interruptions or supply shortages, and they’re preparing very aggressively. They don’t care about the science of why. They know it’s a risk. And their attitude is that they’re going to try to mitigate it or prepare to be responsive and resilient to change.”

Here, we share insights from four SMG research projects, covering topics from self-cleaning solar panels to green loan contracts, to help you consider what it might take to turn sustainability into profit today—and in the future.

Sustainable Savings

Saving energy should equal saving money, but the math doesn’t always add up. A building owner, for instance, might install energy-efficient heaters; a tenant might leave the windows open all winter. Even if landlord and tenant both do their bit for the planet, it might be hard to calculate the actual cost savings. SMG researchers are trying to quantify energy-efficiency savings to help develop incentives for going green.

“If you’re the landlord of a building, I can explain to you the part of the bill that shows you there are now more tenants using more computers, and the part that shows you’re running your building more efficiently because of the lightbulbs you installed.”

Professor Nalin Kulatilaka

One of the most inspired approaches to simultaneously studying, developing, and adopting sustainable technologies while conducting policy and economic research is BU’s Sustainable Neighborhood Lab, which uses urban communities as its laboratory. “We study the city in vivo,” says McManus. “You have to study the living organism and understand its behavior.”

At the Madison Park Housing energy efficiency research project, faculty from various BU schools and colleges are partnering with businesses, including NSTAR and Wells Fargo, to study energy consumption in a public housing project in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. “There are about 875 housing units in the Madison Park complex, a number of which are identical to each other, but their energy use varies significantly,” says McManus. “In the first phase of the study, which began over two years ago, we wanted to find out why that was the case. We needed to measure how people live in order to understand their energy consumption, which meant the community had to be willing to let us study their behavior. We believe that improved information and incentives for both landlord and tenants could reduce energy costs and increase energy efficiency in a large number of properties.”

In Massachusetts and the rest of the Northeast, about 60 percent of the total energy in use comes from heating, cooling, lighting, and powering electric devices in buildings. In the country as a whole, the number is about 45 percent. Reducing the amount of energy used in buildings would not only lower greenhouse gas emissions, but reduce costs.

Even if consumers are willing, they’re stymied by the monthly bill from their utility company, which doesn’t itemize usage. “That means we don’t know what the big problem areas are,” says Nalin Kulatilaka, Wing Tat Lee Family Professor in Management, and a member of the Madison Park team.

One of the issues Kulatilaka is currently researching is how to attract financing for clean energy projects, with a focus on energy efficiency. But again, measurements are fuzzy. “Let’s say you’re putting insulation on your house, or you’re buying a new air conditioner that’s more efficient,” he says. “The actual amount you save depends on things like the weather; what you set your thermostat at; and behavior, like whether you keep your window open in the middle of winter. But how do you measure all this?”

Kulatilaka, who is also codirector of the Clean Energy & Environmental Sustainability Initiative, has developed a methodology that he’s implementing at Madison Park. “I extract effects due to weather and effects due to behavior from total consumption, and isolate the effects of energy-saving efforts,” he says. “So if you’re the landlord of a building, I can explain to you the part of the bill that is the result of a cold winter, and the part that shows you there are now more tenants using more computers, and the part that shows you’re running your building more efficiently because of the lightbulbs you installed. When you can identify savings that are the result of an investment, you can tie that to a loan or a financing plan. If Wells Fargo is going to get into the business of financing sustainability, they need to understand and are very interested in finding out how it’s done on a practical level.”

Kulatilaka and the team are also experimenting with different types of contracts to drive both tenants and landlords to use energy more prudently. “If there’s a saving, and that saving is shared between landlords and tenants, then both sides have an incentive,” he says. “If it’s passed through to the tenant, then the landlord will keep using the lousy equipment. If the landlord pays the bill, the tenant will have the thermostat up and the windows open. So we’re looking at designing contracts that are, in the jargon, incentive compatible.”

Self-Cleaning Solar Panels

Somewhere in the Mojave Desert, the United States is building billion-dollar solar power plants, each of them about 250 megawatts and containing over a million square meters of glass. “They’re reflecting light and focusing on a central point, and an enormous amount of heat is then converted into energy,” says Nitin Joglekar, associate professor of operations & technology management.

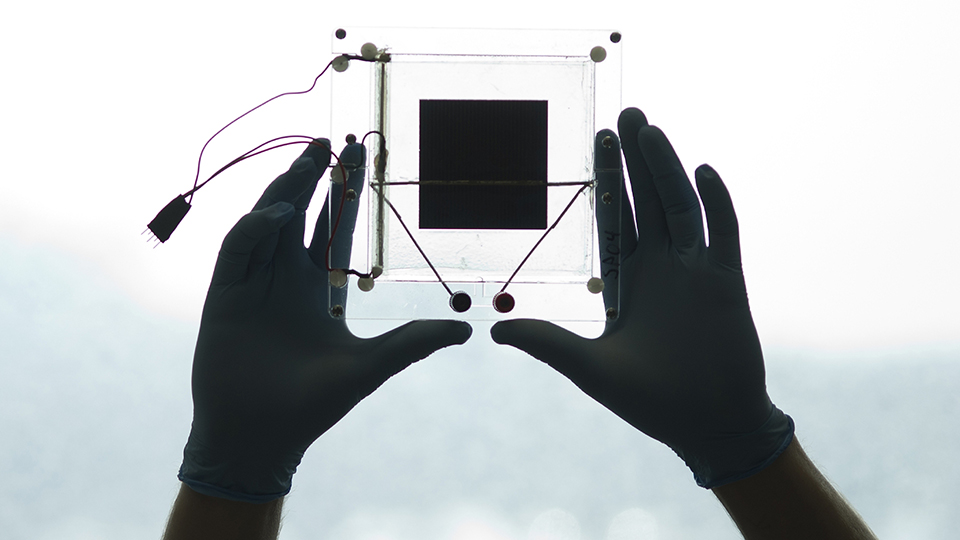

BU researchers have invented self-cleaning solar panels—watch the dust shake away. Video by Joe Chan. Photo by Cydney Scott

It’s cutting-edge stuff and funded by the Department of Energy, which gave BU close to a million dollars to study a very special problem: dust.

“The dust sucks up anywhere between 10 and 30 percent of power because light gets scattered by dust,” says Joglekar. “And you won’t believe what the best technology currently is to fix the problem. It’s something called deluge cleaning. That’s a euphemism for bringing in tankers and tankers full of water from miles and miles away, and throwing the water onto these expensive panels. It’s horrible. It knocks off some of the dust, and also creates some damage. The Department of Energy realized this had to be fixed.”

“Right now, the solution to the loss of 10 percent of power is to build a bigger plant. With the new technology, you don’t need to build the extra 25 megawatts, so that will be the first saving.”

Associate Professor Nitin Joglekar

Malay Mazumder, a research professor at the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and one of Joglekar’s colleagues on the project, had designed self-cleaning technology for Mars and lunar missions as part of NASA-supported research. The BU team is now developing a variation of that technology on firmer ground, and conducting cost and profit analyses in a campus lab.

The technology is made up of thin, transparent conducting wires “that look a little like the wires that run across your car’s rear window,” says Joglekar. “[On your car,] the wires warm up the glass, and warming up the glass evaporates the water. We’re using the same idea, only in this case you want to shake the dust loose. The Department of Energy believes that over time this technology may solve the dust problem.”

It will also bring down costs. “Right now, the solution to the loss of 10 percent of power is to build a bigger plant,” says Joglekar, who is working on cost analysis. “If you need 250 megawatts of solar energy, you build 275 megawatts to compensate. With the new technology, you don’t need to build the extra 25 megawatts, so that will be the first saving. As taxpayers, we’re currently paying $1.4 billion on this, but the fixed cost could go down to $1.1 billion. The second factor is that your variable cost, the amount of water you’re shipping in tankers, goes down. We’re writing a paper right now on how to come up with levelized cost. It will probably take between 7 and 10 years to install these power plants at the commercial level. So we’re trying to set standards and change the game.”

Responding to Red Tape

Kira Fabrizio, assistant professor of strategy & innovation, focuses on how strategy is impacted by and affects government regulation. “My research looks at how firms respond to regulation, how regulation shapes the profitability of firms’ strategies, and even how regulation responds to firms’ strategies,” she says. “There is a lot of regulation related to environmental sustainability, because companies don’t bear the cost for the impact they’re having on the environment. We all do. One example of the regulation is the Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) passed by about half the states in the US. It requires electric utilities to acquire a certain percentage of their electricity from renewable energy sources. It’s more expensive than traditional electricity, so the utilities wouldn’t buy it without this rule in place. The idea is to increase investment in renewable energy generation.”

The states that have enacted RPS set a target percentage that must be reached by a certain date; in Massachusetts, for instance, 15 percent of energy must come from renewable sources by 2020. In California, the number is 33 percent. “That’s a significant increase in renewable energy,” says Fabrizio, “and there’s a real risk of pushback from the public once the higher costs start hitting people’s bills. And that means there’s a risk of these policies being repealed in the future.”

In 2013, the Journal of Law, Economics and Organization published Fabrizio’s study, “The Impact of Regulatory Uncertainty on Renewable Energy Investments.”

Her project looked both at the impact of RPS on investment in renewable energy generation, as well as at how firms respond to regulatory or policy risk. “We were expecting that RPS policies would increase investment in renewable energy generation,” she says. “That’s the intended purpose. In states where there was more policy certainty, you saw the intended result. But in the states where there was less certainty about future policy stability, you didn’t see any increase on average in renewable energy generation investment in response to RPS. Although we need regulation to promote investments in sustainability, regulation is accompanied by regulatory uncertainty. If an investment is made with a long-term view, for instance, what happens to the return on that outlay if policy changes? This kind of uncertainty undermines the effectiveness of policy. In my view, policymakers need to be managing and reducing the policy risk if they hope that the policy will achieve its intended goal.”

Driving Dividends (in a hybrid, probably)

Is there any real financial benefit for companies that take advantage of corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Does CSR maximize shareholder value? The short answer to both questions is yes, according to a study by Associate Professor Rui A. Albuquerque and Assistant Professor Yrjo Koskinen, both of the finance department.

“It’s more than thinking about the company in isolation. Consumers are demanding that companies supervise not only their own operations, but their suppliers’ operations.”

Associate Professor Rui A. Albuquerque

Albuquerque, Koskinen, and a University of Iowa colleague collected 23,803 firm-year observations from 2003 to 2011, and found that CSR, which includes environmental measures, leads to lower systematic risk and higher valuation. “There are still a lot of people out there who think that CSR just provides perks, with no benefit to shareholders,” he says. “But what we’ve found is that firms with more CSR have lower cost of capital and higher valuation.”

Albuquerque says the 2013 scandal involving Apple and labor violations in China underscores the need for companies to manage CSR along their supply chain as well. “It’s more than thinking about the company in isolation,” he says. “Consumers are demanding that companies supervise not only their own operations, but their suppliers’ operations. And we cite some evidence from other studies in our paper that there’s an effective price premium on products from companies that have more CSR.”

But Albuquerque, whose study won a European Corporate Governance Institute best paper award, also offers a caveat. “There’s low-hanging fruit for some companies, and the low-hanging fruit might be disappearing,” he says. “The idea is that the more firms adopt CSR, the harder it will be to take advantage of it. Because once that space is taken over, you’re going to have to make a bigger effort than everybody else to be heard and for your CSR to be valued relative to everybody else in the industry. There might be a risk that if you’re too late in the game, then you won’t get as much benefit as the firms that are already doing it.”

The Final Word

Kristen McCormack, assistant dean for sector initiatives, concludes that tomorrow’s business leaders must be literate and knowledgeable about sustainability practices. “Ten years ago, the topic of sustainability was not on the radar of most companies. Today, an increasing number of industry leaders have integrated sustainability into their core strategies. These companies have moved beyond thinking of environmental issues in terms of regulatory compliance. Rather, they see the opportunity sustainability strategies provide—whether it’s creating high-performing, resilient supply chains or developing new sustainable products, services, and business models. All of these actions can produce company financial rewards and reduce risk. Sustainability will play a key role in the future growth of the global economy regardless of the industry in which you choose to make your career.”