Heintz, Joseph, C.Ss.R. (1865-1940)

Promoter of Non-Coercive Direct Evangelization in a Context of Protestant-Catholic Competition in Belgian Congo

Joseph Heintz, C.Ss.R. (1865-1940) played a leading role in the Redemptorist mission in Bas-Congo, directing its activities as Permanent Visitor and then as Apostolic Prefect from 1904-1929. His contribution to Catholic missiology is only beginning to be explored. While there have been two major academic studies of the Redemptorist mission to Congo, both focus exclusively on the period up to 1919, and there are no book-length treatments of Heintz himself.[1] Michaël Kratz reproduces three important archival documents written by Heintz as appendices to his 1970 study; since Heintz only published brief articles in now-obscure publications, these provide important insights into his missiology, though only one is available in English translation.[2] Unfortunately, detailed studies do not yet exist of Heintz’s involvement in important events from after 1919, including his interaction with Kimbanguism and his involvement in expanding the Redemptorists’ focus on education and training of indigenous clergy.[3]

Although the sources are sparse, they are sufficient to indicate that Heintz, as apostolic prefect of the Redemptorists, played an important role in regularizing, implementing and extending a strategy of direct and non-coercive evangelization that was innovative in his context: the chapel-school method. This method developed in a historical context marked by the atrocities of the Congo Independent State, in sharp competition with Protestants who were already established on Redemptorist territory, and in reaction to the more forceful missionary methods used by the neighboring Jesuits. In this summary, a brief biographical overview of Heintz’s career and contributions is followed by an exploration of how and why, in light of the various tensions within Heintz’s missiology, the chapel-school method could develop in this historical context.

Biographical overview

Joseph Heintz was born in Bastogne, Belgium in 1865, and was ordained as a Redemptorist priest in 1891 at age 26.[4] He was not a particularly gifted student, and had to work hard to succeed.[5] Although the Redemptorists were not a missionary order, after long negotiations they had accepted Belgian King Leopold II’s request to start a mission in the Lower Congo region of the Congo Independent State, a region that was under Leopoldian sovereignty since the Berlin Conference of 1885.[6] Their original goal was to focus on the spiritual nurture of the expatriate workers living along the newly-constructed Matadi-Leopoldville railway line.[7] The first Redemptorist missionaries were sent in 1899, and Heintz soon joined them. Responding to an 1898 call for volunteers for the Congo mission, Heintz wrote to his superior: “With all my heart, I offer myself to go if Your Reverence finds me apt for these far regions […]. I would be happy to go work there and to offer even my life for our poor Blacks.”[8]

Arriving in Lower Congo, Heintz joined a mission that was relatively disunited, with different priests trying out a variety of methods in different areas, but all agreeing that the mission must focus on ministry to rural Congolese, moving quickly away from the original plan and from the artificial environment of the railway towns.[9] Heintz soon settled at the Tumba mission, where he directed the mission’s first simple catechist school that had been founded by Father Simpelaere in 1903.[10] After the death of Simpelaere in 1904, Heintz replaced him as Permanent Visitor; this put him in charge of the mission, which was still a vice-province of the Apostolic Vicariate of Congo.[11] During the first years of his appointment, he also undertook numerous voyages of exploration, led large groups of missioners in “apostolic expeditions” involving itinerant preaching, and founded outposts in several new villages.[12] Thus, early in his career, Heintz already exhibited the dual focus which would later develop into the Redemptorists’ signature style: holding together centralized education for catechists with expansion through itineration and outposts in remote areas.

One of Heintz’s most significant contributions to the Redemptorists’ mission method was his application and extension of the new evangelization method of chapel-schools, pioneered by Simpelaere in early 1904 just before his sudden death later that year.[13] This method contrasted with the chapel-farms of the neighboring Jesuits, but was markedly similar to the strategies used by Protestant missionaries in the Lower Congo. Unlike the Jesuits, Redemptorists did not limit their focus to children, and they rejected the use of coercive child recruitment that had earned the Jesuits the reputation of child-stealers.[14] Like the Protestants, they evangelized people of all ages directly in their own village contexts through catechist-manned outposts, rather than seeking to create a completely alternative Christian social structure.[15] When the impressive results of the new method had convinced even the most skeptical missionaries of its value, Heintz played an important role in making it mandatory for all as part of the new Rule for the Vice-Province.[16] Already by 1909, the Redemptorists were known as far as Rome for being more successful than the other Catholic missions,[17] and this success was the impetus for the upgrading of the Redemptorist mission to the status of an Apostolic Prefecture by the Propaganda in Rome.[18]

Heintz was designated as the first Apostolic Prefect in 1911. At this time, he was already a proven missionary – a man of initiative, universally appreciated by his colleagues and trusted by his superiors, and known for his sympathy to the indigenous population, who affectionately called him Tata Hienzi.[19] He had a jovial, benevolent personality and loved a good meal; he was also clearly a gifted and diplomatic negotiator.[20] During the war, when financial support and contact with Belgian superiors were cut off, Heintz promoted agricultural self-sufficiency for the missions; when the inability to pay catechists led to defections of some villages to Protestantism, he spearheaded efforts to increase the priests’ presence in the villages through itineration.[21]

Heintz’s dual focus on education at the mission and evangelization in the villages continued throughout his years as Apostolic prefect. His strong predilection for education led him to expand the role of the central missions and to improve the level and quality of education being offered to Congolese. In 1911 he initiated a reform of catechist training schools, articulating the necessity for improved catechist training to combat the problem of runaways. This reform, which led to a definite improvement in the quality and number of catechists, involved the banning of the harshest methods of discipline – the withholding of food and the use of chains and the chicotte[22] – and allowed the students more contact with their home villages and continuing education at the central mission after graduation.[23] Later in his career, experiencing frustration about the fact that many Congolese conversions to Catholicism seemed to be superficial, Heintz continued to focus on education through a new emphasis on the importance of the central missions.[24] He pioneered the first complete teacher-training programs in the country beginning in 1924,[25] and founded a Petit séminaire for the training of indigenous clergy in the same year.[26] The Redemptorist schools provided a high level of education for the time, offering teacher training certifications to both boys and girls. The mission’s professional schools also trained many who would become employees of the colonial administration or of private companies.[27] In addition to the centralizing focus on mission stations, however, Heintz also continued to pursue itinerant evangelism in remote areas, writing in 1911, “I absolutely must roam in the bush, for I suffocate in cities,” and delegating administrative work to others to permit him to travel more.[28]

Simon Kimbangu began his prophetic ministry in Redemptorist territory in 1921. Participating in the universal condemnation of Kimbangu by Catholic missionaries, Heintz vigorously opposed the movement, making the case that it was a menace to public order and encouraging the State to suppress it vigorously.[29] Consistently with his patriotism and his enmity toward Protestants, whom he saw as his “nastiest and most powerful antagonists,”[30] he particularly deplored the Protestant support for movements like Kimbanguism, which in his view was motivated by the aim to chase Catholics and the State out of the colony completely.[31] Not surprisingly, he was hated by Kimbanguists.[32]

At the time of Heintz’s resignation as Apostolic prefect in 1929, the mission counted nearly 40,000 Christians, just over 11,000 catechumens, and 815 catechists. Heintz continued to live in Tumba until he was forced to return to Belgium due to poor health at age 69.[33] However, homesickness and a desire to keep helping the mission led him to return to Congo three years later, where he died in 1940 at age 75.[34]

The chapel-school method in historical context

In this section, I explore the chapel-school method in more detail in light of Heintz’s overall missiology. First, I review the methods already in use by Catholic and Protestant missionaries in or around the Bas-Congo area, in order to show how the chapel-school method constituted an innovation at the time. I then explore the reasons why Heintz might have chosen to lead the Redemptorists in this direction at this time, despite various tensions and inconsistencies in his missiological thinking.

When the Redemptorists arrived in Lower Congo in 1899, they found a harsh and exploitative colonial situation, with the indigenous Kongo people being decimated by the combination of the slave trade, sleeping sickness, porterage for the railroad, forced labor and taxes.[35] Moreover, they found that Protestant and Catholic missionaries, both already hard at work in this context, were developing very distinct approaches to the colonial regime and were in direct competition nearly from the beginning. The Protestant missions had arrived in 1878, and initially supported Leopold’s efforts to gain sovereignty over the territory because his proclaimed intent to support missionaries of all confessions made him seem like a better candidate than France or Portugal, the other contenders.[36] In the year following the 1885 Berlin Conference, however, Leopold successfully pressured the pope to limit Catholic missionaries in the Independent State to those of Belgian nationality, while simultaneously working to convince various Belgian Catholic orders to undertake missions in Congo.[37] The Scheutists arrived in 1887, and the Jesuits in 1891, followed by a stream of other missionary orders.[38] Leopold soon began to strongly favor the Catholic missions with land concessions and access to state steamers to transport their goods.[39]

As both Catholic and Protestant missionaries moved into the interior, there was intense competition to establish missions in the best locations and to win local villages to each confession.[40] The Lower Congo, where the Redemptorists would settle, was one area of particularly fierce competition.[41] As Anne-Sophie Gijs has shown, Catholic missionaries’ relationship to State officials at this time was characterized by a complex mix of patriotism, pragmatism, mutual suspicion and mutual interdependence. While many Catholic missionaries felt free to address private critiques to colonial officials for exploitative policies, they tended to remain publicly loyal.[42] Protestants, on the other hand, fairly soon began to openly condemn the violence and abuse of the rubber extraction and forced labor regimes, providing eye-witness accounts to support the British-based press campaign designed to expose the atrocities of the Congo Independent State.[43] Criticism of the regime came both from within and without. A state-appointed Commission of Inquiry in 1905 described the regime’s abuses and the collusion of Catholic missions with the state, and concluded that the state was nothing more than a cover for a financial enterprise aimed at maximizing the wealth of King Leopold.[44] However, the British press campaign seems to have played an even more significant role in leading to the Belgian annexation of Congo as a colony in 1908, as well as in helping to sour Belgian colonial opinion against the Protestant missionaries.[45]

Before the arrival of the Redemptorists, mission practice among both Protestants and Catholics had already moved through some initial developments that demonstrated a variety of missiological assumptions. Ruth Slade has shown that both Catholic and Protestant missionaries in this early period began their mission efforts by attempting to segregate Africans from their local “pagan” contexts through the construction of alternative communities, based on the assumption that Christianization would require starting a new social order from scratch.[46] The Catholic orders based their efforts on two additional assumptions. First, they believed that it was nearly impossible to evangelize adults, so that alternative communities would have to be populated with children.[47] Second, despite their occasional critiques of the state’s exploitative policies and poor morals, Catholic missionaries still conceived of the state as their partner in a work of civilization and Christianization. They frequently appealed to state coercion to support their combat against pagan practices, to force local people to relocate, or to make them construct chapels.[48] The combination of these three assumptions led the early Catholic missions to focus initially on the founding of large school colonies populated with children that the state had freed from slavery.[49] These colonies received subsidies from Leopold and served as a source of soldiers to police his system of forced labour.[50] After realizing that this system did not produce enough trained catechists to be able to evangelize the rest of the area effectively, the Jesuits pioneered the chapel-farm system in 1893. This involved three innovations: first, all the pupils were retained to receive training as catechists instead of being sent into the military.[51] Second, groups of children were sent out under the supervision of a catechist to establish themselves on the outskirts of villages, where they lived a strictly disciplined lifestyle, supported themselves through agricultural work and taught catechism to the villagers.[52] In this way, the Christian influence moved beyond the confines of the school colonies into the villages, and the Congolese themselves were being integrated into the work of evangelization, even while retaining a certain distance from the village social structure.[53] The hope was that these children would marry each other and found Christian villages.[54] Third, the new chapel-farms could be financially self-supporting. The chapel-farm system spread rapidly throughout the area;[55] however, as the anti-slavery campaign drew to a close around 1894, this source of children dried up, and in 1892 the state authorized Catholic missions to recruit “orphans” in the villages. The ongoing forcible recruitment of children by the State, sometimes in conflict and sometimes in collaboration with the Jesuits, soon provoked widespread fear and hatred of both missions and state on the part of indigenous people.[56]

In contrast with the Catholics, the Protestants did not have a major focus on recruiting children and tended not to take the freed slaves that were being offered to missionaries by the State.[57] In addition, while the villages that tended to grow up around the Protestant mission stations had a very distinct structure from that of the local villages, they were under less strict control by the central station than the Catholic Christian villages.[58] Like the Jesuits, the Protestants also eventually moved toward an increased focus on evangelism in remote areas, but they did so not through chapel-farms but by training indigenous catechists and sending them out to evangelize, thus creating a large network of outposts.[59]

When the Redemptorists arrived in 1899, then, they found the neighboring Jesuits and Protestants both engaged in outreach to villages, but using very differing methods. Through a process that proceeded in fits and starts, they moved toward developing a method that would fit with the ethos of their own order while allowing them to develop a ministry that moved beyond the confines of the railway towns, with their artificial environment, and into the indigenous villages. At least three factors contributed to helping them develop and refine their chapel-school method. I will illustrate the significance of each factor in Heintz’s own thinking by quoting from documents he wrote between 1907 and 1925.

First, it was deeply ingrained in the Redemptorist ethos that apostolic outreach must be universal in scope. In the Belgian context, their work had involved evangelism of the “most abandoned souls” and especially of those who lived in rural areas; they had been trained to reject any missionary approach that would limit their work to a single segment of the population.[60] Because of this background, they were predisposed to question the assumption that missionary work should focus only on children while assuming that the adults were irredeemable. Some even drew a clear link between the methods their order had used in Europe, and the necessity to extend their apostolate to people of all ages in Congo.[61] In the first years of the Congo mission, the Redemptorists’ experience trying to work within the artificial environment of the railway line both confirmed this desire to reach out to the remotest people in their own social context,[62] and proved to them that adults could convert.[63] Their lack of cross-cultural training before coming to Congo may have also been a factor in predisposing them to draw more directly on the ethos of their order and on missionary methods practiced in Belgium, leaving them freer to question the missiological assumptions of other orders.

This background of working with the poor and abandoned seems to have played a role in encouraging the Redemptorists to move away from the coercive recruitment methods of the Jesuits, despite various initial attempts to try the chapel-farm method, and may have led them to take a gentler approach to the discipline of students in their schools. There is evidence of such an influence in the Rule of the Vice-Province, written by Heintz in 1908-1909. In a way that would have contrasted with the ethos of a Jesuit school colony, Heintz emphasized the necessity for gentle discipline methods in catechist training schools. He limited the right to practice corporal punishment to the Father Superior, urged the “Fathers and Brothers” who related to the children to “imitate Jesus, especially in his gentleness, his humility and his patience,” and allowed the children daily times of relaxation for “indigenous games.”[64] In another document that laid out Heintz’s rationale for the chapel-school system, he also noted that one of the advantages of refusing to engage in child recruitment was that adults, no longer fearing to lose their children, would be attracted to the chapel-school of their own volition:

[T]hough the Jesuits have masses of children taken by force from the village and living alone on their chapel-farms, they have not a single indigenous adult. We, on the contrary, have many adults who have nothing to fear from our evangelization, which is completely selfless and not at all mercantile.[65]

Although Heintz retained the concern to recruit a sufficient number of children to populate catechist schools, he was committed to do so “without offending the natives.”[66] Moreover, the fact that he promoted this method even though the cessation of farming led to much higher costs for the mission suggests that he genuinely believed that a less forceful method was the right choice.[67]

In addition, the Redemptorists’ desire to minister to people in their own context, as per the ethos of their order, may also have predisposed them to adopt a method that involved placing a chapel right in the center of a village instead of on its outskirts,[68] even though this remained in tension with the idea, propagated through the method of catechist education, that Kongo social structure needed to be profoundly revamped. It is important to note that the Redemptorists adopted this method without any appeal to principles of inculturation. Missiological ideas about “adaptation” only began to enter the discourse of Belgian Catholic missionaries in the early 1920s.[69] On the contrary, even later in life Heintz expressed a very low view of Kongo culture that was consistent with the typical Catholic missionary attitude in Congo at the time:

Among all the human races, the black race is ranked last… It is said that the blacks are ignorant, depraved, inconstant, and it is said correctly. If then it has been necessary to overcome so many obstacles, deploy so many efforts for so many centuries to establish Christianity in Europe, incomparably more work and time will be required to establish a seriously practiced Christianity among the African tribes… One could list many obstacles, but the great obstacle, the greatest that opposes true civilization and the improvement of the black, is his mentality that will not die in a day; it is his profoundly rooted superstition.[70]

If Redemptorists still accepted the strategy of putting chapel-schools in the center of villages, in spite of the belief that Kongo culture could only be redeemed through a complete break with its existing mentality, and despite the risk of children being overcome again by their “pagan environment,”[71] this may somehow have been connected to a Redemptorist philosophy of respecting the marginalized enough to reject coercion.

Second, the close contact with Protestants in the Bas-Congo region was significant both because it exposed the Redemptorists to the method of placing a large number of catechists into outposts, and because the strong competition with Protestants made the Redemptorists anxious to find a method that could conquer the region as quickly as possible with the minimum number of personnel. Father Simpelaere, Heintz’s predecessor, was incredulous at the number of catechists already placed by the Protestant missionaries. He grudgingly admired the accomplishments of BMS missionary W. H. Bentley, whom he had met on a train voyage around 1900 and with whom he developed a genuine friendship.[72] In 1904, just before succumbing to fever in the middle of that year, Simpelaere stopped the forced recruitment of children and moved toward a system of outposts manned by catechists who were trained at the central mission.[73] Soon, the Redemptorists also dropped the farming aspect of their outposts.[74] Both Simpelaere and Heintz were conscious that they were essentially copying the Protestant method. However, Simpelaere seemed to be motivated at least partly by a genuine admiration for a method that worked.[75] Heintz, unencumbered by personal friendships with Protestant missionaries, saw the adoption of the Protestant method as primarily a way to beat these hated rivals at their own game. Speaking of the new method, he wrote,

this is the strategy we use to remain at peace with the adults, and especially to thwart the craftiness of the Protestants. Whenever we wanted to enter a new village, they would go around everywhere shouting out that we were coming to kidnap the children and to grow field crops, while waiting for the day when we could crowd out indigenous agriculture altogether. Our system, for the moment, broadly speaking at least, is the system of the Protestants themselves. We think this is best, given our particular situation of endless struggle against the Protestants, with both of us on situated on the same battlefield. Is it not legitimate for us to use the same tactics as they do – tactics that have succeeded admirably for them up to this day? They have noticed our new strategy and have been frightened, for they have immediately observed the happy rewards that we are reaping from this new line of conduct. Their slanders no longer serve any purpose, and the indigenous people, obtuse as they are, laugh in their faces when they come to warn them that we will kidnap their children or take their croplands.[76]

A sense of bitter rivalry with Protestants also explains Heintz’s attempts to improve the chapel-school method. One of the main shortcomings of the method as it was initially practiced was the low level of education of catechists. Noting this difficulty, Heintz connected it with the Protestant threat:

We know perfectly well that it is difficult to keep the catechists in school for several years, due to the necessity we are in to place them in villages immediately, where they are calling for us… [H]owever minimal the talents of a catechist placed so hastily in this way, he prevents the Protestant from entering a village that otherwise would escape us forever. But his education is not finished, and we will feel the consequences for a long time to come.[77]

Under Heintz’s leadership, the Redemptorists focused on tackling this shortcoming; since insufficient catechist training was also a problem for the Protestants, they realized they could gain an advantage over the Protestants by acting for improvement in two areas. First, they worked to improve the training of catechists. Second, they made sure that the Redemptorist priests itinerated more than the Protestants, in order to provide closer supervision to the catechists. Ntima argues that village work and central station work were thus able to feed off each other in a dialectical relationship, allowing the Redemptorists, even more than their Protestant rivals, to install themselves firmly in the heart of rural villages.[78]

A third important factor that played a role in the adoption of the chapel-school method was simple pragmatism along with a desire to look good. The coercive aspects of the Jesuits’ chapel-farm method were coming under fire in Belgium, especially after the 1904-1905 Commission of Inquiry published its report.[79] Although Kratz makes the point that the Redemptorists began their shift away from chapel-farms before this Commission was appointed,[80] they may nevertheless have sensed that public opinion was turning against draconian methods of “evangelization.”

The simple fact that local people responded better when the Redemptorists avoided coercive methods played a role as well. Heintz described the conflict and dysfunction that had plagued the Redemptorists’ early attempts at chapel-farms. The attempt to farm had proven particularly ineffective because villagers, children and priests were in continual conflict. The priests accused the children of laziness, the children accused the priest of letting them die of hunger, and the villagers complained about the invasive goats and chickens or accused the priest of trying to claim their livestock as his own. In short, there was a good dose of pragmatism in Heintz’s depiction of the shift to chapel-schools as “forced by circumstances, by events, and above all by a realization of the futility of the efforts made until then,” as well as in his observation that the failed farms and forced recruitment simply made the priest look like a “profit-seeker” and a “land-grabber.”[81] The method’s immediate success in winning converts and even in gaining back villages that had hitherto been Protestant must have encouraged the Redemptorists to continue using it.[82] Redemptorist priest Dufonteny, writing in 1925 about the shift to chapel-schools, noted that “this system had the advantage of provoking conversions that all the missionaries believed to be impossible.”[83]

Additional evidence that pragmatism played a role in Heintz’s support for this method is the fact that he was willing to resort to coercion at other times. In many ways, Heintz’s perspective did not differ from that of other Belgian missionaries working in Congo. During the Kimbanguist revival, he had no compunctions about calling on the force of the state to crush the movement. A 1909 letter to the Minister of Colonies provides evidence that despite various critiques of the exploitative characteristics of the regime, Heintz fully expected the state to openly support and favor Catholics, making its coercive power available to the missions to enforce Catholic standards of morality.[84] In short, the fact that Heintz held to such a strongly theocratic vision throughout his life suggests that a certain amount of pragmatism must have lain behind his support for a relatively non-coercive method.

Conclusion

The chapel-schools provide an intriguing example of how a relatively non-coercive method, directly inspired by Protestant practice, could develop in spite of a total disdain for Protestant theology and an otherwise strongly theocratic worldview that assumed a stance of collaboration with the state’s coercive force. In this summary, I have traced Heintz’ role in supporting and extending the chapel-school method, and analyzed the various factors that played a role in encouraging his choice of this method as the Redemptorists’ official strategy. Although Heintz was a major proponent of chapel-schools, a tension persisted in his thought between his predilection for this relatively gentle approach and his strongly theocratic and paternalistic vision. Heintz showed a genuine desire to minister to the marginalized and to express the ideals of the order through non-coercive methods. Yet his never-ending desire to “defeat” Protestant “heresy,”[85] his disdain for Kongo “superstition,” and his strongly patriotic and collaborative stance toward the state sometimes undermined his Redemptorist ideals. Examining Heintz’s thought in its historical context makes it clear that the choice of the chapel-school method was far from a given in its time, but was rather an innovation that occurred in spite of, rather than because of, the fraught and exploitative context of early 20th-century Congo.

[1] The two most important studies are Michaël Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920) (Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970); Kavenadiambuko Ngemba Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: 1899-1919 : étude historico-analytique (Gregorian Biblical BookShop, 1999).

[2] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization”.

[3] Some letters from Heintz to the colonial officials in the context of the Kimbanguist uprising can be found in E Libert, “Les Missionnaires Chrétiens Face Au Mouvement Kimbanguiste. Documents Contemporains (1921),” Études D’histoire Africaine 2 (1971): 121–54.

[4] Maur. (de) Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” Biographie coloniale belge (Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1955), 381, http://www.kaowarsom.be/en/notices_heintz_joseph.

[5] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 137.

[6] Ibid., 41–42.

[7] Ibid., 73.

[8] Ibid., 138, my translation.

[9] Ibid., 64–66, 86.

[10] Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 381.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 382; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 237–39.

[13] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 307; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 139.

[14] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization in Congo (Ca. 1908-1911),” 9.

[15] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 319–24.

[16] Ibid., 308–9.

[17] Ibid., 331.

[18] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 232.

[19] Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 139.

[20] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 138–39; Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382.

[21] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 313–14.

[22] A hippopotamus-hide whip that was widely used in the Congo Indpendent State to enforce compliance with the regime. SeeDavid Van Reybrouck and Isabelle Rosselin, Congo, une histoire (Arles: Actes Sud, 2012), 112.

[23] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 173–74.

[24] Ibid., 334.

[25] Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382.

[26] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 339.

[27] Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382.

[28] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 290–91.

[29] Augustin Bita Lihun Nzundu, Missions catholiques et protestantes face au colonialisme et aux aspirations du peuple autochtone à l’autonomie et à l’indépendance politique au Congo Belge (1908-1960): effort de synthèse (Roma: Pontificia Università gregoriana, 2013), 418–19; Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382.

[30] 1921 letter cited in Bita Lihun Nzundu, Missions catholiques et protestantes, 395.

[31] Libert, “Les Missionnaires Chrétiens Face Au Mouvement Kimbanguiste. Documents Contemporains (1921),” 41 as cited in; Bita Lihun Nzundu, Missions catholiques et protestantes, 559–60.

[32] Meulemester, “Heintz (Joseph),” 382.

[33] Ibid., 383.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 232.

[36] Ruth Slade Reardon, “Catholics and Protestants in the Congo,” in Christianity in Tropical Africa: Studies Presented and Discussed at the Seventh International African Seminar, University of Ghana, April 1965, ed. International African Seminar (London: published for the International African Institute by the Oxford UP, 1968), 84.

[37] Ruth M. Slade, King Leopold’s Congo; Aspects of the Development of Race Relations in the Congo Independent State. (London, New York, Oxford University Press, 1962), 147.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Reardon, “Catholics and Protestants in the Congo,” 86.

[40] Ibid., 83.

[41] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 148.

[42] Anne-Sophie Gijs, “Émile Van Hencxthoven, Un Jésuit Entre Congo et Congolais: Conflits de Conscience et D’intéréts Autour Du Supérieur de La Mission Du Kwango Dans l’État Indépendant Du Congo (1893-1908),” Revue D’histoire Ecclésiastique 105, no. 3–4 (July 2010): 675–76.

[43] David Lagergren, Mission and State in the Congo. A Study of the Relations between Protestant Missions and the Congo Independent State Authorities with Special Reference to the Equator District, 1885-1903, Studia Missionalia Upsaliensia, 13 (Lund, Gleerup, 1970), 346–47; Marvin D Markowitz, Cross and Sword: The Political Role of Christian Missions in the Belgian Congo, 1908-1960 (Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, 1973), 6.

[44] Félicien Cattier, Étude sur la Situation de l’État Indépendant du Congo (Paris; Bruxelles: Larcier; Pedone, 1906), 341; as cited in Van Reybrouck and Rosselin, Congo, une histoire, 118.

[45] Gijs, “Émile Van Hencxthoven, Un Jésuit Entre Congo et Congolais,” 658; Reardon, “Catholics and Protestants in the Congo,” 87.

[46] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 154–55.

[47] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 279; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 89–90; Gérard Ciparisse, “La naissance des fermes-chapelles au Congo (1895-1900),” Cahiers congolais de la recherche et du développement 16, no. 4 (1970): 87.

[48] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 87; Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 359–60.

[49] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 280.

[50] Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost : A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), 133–34.

[51] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 159; Gijs, “Émile Van Hencxthoven, Un Jésuit Entre Congo et Congolais,” 657.

[52] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 159; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 140.

[53] Gijs, “Émile Van Hencxthoven, Un Jésuit Entre Congo et Congolais,” 656; Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 283; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 95.

[54] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 284.

[55] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 160.

[56] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 279, 284; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 96–97. It is difficult to reconstruct the extent to which Jesuits themselves engaged in forcible recruitment for chapel-farms, and to what extent they relied on other forms of persuasion, including financial incentives. Ntima (p. 96) makes the case that Jesuits and the State were certainly engaged in a level of competition for control over the local populations at this time.

[57] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 285; Cattier, Étude sur la Situation de l’État Indépendant du Congo, 277.

[58] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 286.

[59] Slade, King Leopold’s Congo, 159.

[60] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 306.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 79.

[63] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 299; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 73.

[64] J.M.J.A., Règlement de la Vice-Province du Congo, 30, 62; my translation; as cited in Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 353.

[65] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization in Congo (Ca. 1908-1911),” 6.

[66] Ibid., 9.

[67] Ibid., 6–7.

[68] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 319.

[69] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 335.

[70] 1919 circular by Heintz as cited in Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 335; my translation.

[71] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization in Congo (Ca. 1908-1911),” 6.

[72] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 116; 120-121.

[73] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 301–2; Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 127–28.

[74] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 305.

[75] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 121.

[76] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization in Congo (Ca. 1908-1911),” 8.

[77] Ibid., 19.

[78] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 180–81.

[79] Cattier, Étude sur la Situation de l’État Indépendant du Congo, 277–92.

[80] Kratz, La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 305.

[81] Heintz, “Notes on Evangelization in Congo (Ca. 1908-1911),” 5.

[82] Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 9.

[83] Georges Dufonteny, “Historique de notre méthode d’apostolat (ca. 1925),” in La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920), by Michaël Kratz (Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970), 357.

[84] Joseph Heintz, “À Monsieur Renkin, Ministre des Colonies, 15 août 1909,” in La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920), by Michaël Kratz (Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970), 364–70.

[85] Heintz in 1919 as cited in Ntima, La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo, 236.

By Anicka Fast

Bibliography

Primary

Cattier, Félicien. Étude sur la Situation de l’État Indépendant du Congo. Paris; Bruxelles: Larcier; Pedone, 1906.

Dufonteny, Georges. “Historique de notre méthode d’apostolat (ca. 1925).” In La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920), by Michaël Kratz, 356–58. Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970.

Heintz, Joseph. “Notes on Evangelization (ca. 1908-1911).” Edited by Michaël Kratz. Translated by Anicka Fast, 2016.

_____. “À Monsieur Renkin, Ministre des Colonies, 15 août 1909.” In La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920), by Michaël Kratz, 364–70. Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970.

J.M.J.A. “Règlement de la Vice-Province du Congo.” In La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920), edited by Michaël Kratz, 16th ed., 348–55. Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970.

Secondary

Bita Lihun Nzundu, Augustin. Missions catholiques et protestantes face au colonialisme et aux aspirations du peuple autochtone à l’autonomie et à l’indépendance politique au Congo Belge (1908-1960): effort de synthèse. Roma: Pontificia Università gregoriana, 2013.

Ciparisse, Gérard. “La naissance des fermes-chapelles au Congo (1895-1900).” Cahiers congolais de la recherche et du développement 16, no. 4 (1970): 70–87.

Gijs, Anne-Sophie. “Émile Van Hencxthoven, Un Jésuit Entre Congo et Congolais: Conflits de Conscience et D’intéréts Autour Du Supérieur de La Mission Du Kwango Dans l’État Indépendant Du Congo (1893-1908).” Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique 105, no. 3–4 (July 2010): 652–88.

Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost : A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Kratz, Michaël. La mission des rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: la période des semailles (1899-1920). Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1970.

Lagergren, David. Mission and State in the Congo. A Study of the Relations between Protestant Missions and the Congo Independent State Authorities with Special Reference to the Equator District, 1885-1903. Studia Missionalia Upsaliensia, 13. Lund, Gleerup, 1970.

Libert, E. “Les Missionnaires Chrétiens Face Au Mouvement Kimbanguiste. Documents Contemporains (1921).” Études D’histoire Africaine 2 (1971): 121–54.

Markowitz, Marvin D. Cross and Sword: The Political Role of Christian Missions in the Belgian Congo, 1908-1960. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, 1973.

Meulemester, Maur. (de). “Heintz (Joseph).” Biographie coloniale belge. Bruxelles: Académie royale des sciences d’outre-mer, 1955. http://www.kaowarsom.be/en/notices_heintz_joseph.

Ntima, Kavenadiambuko Ngemba. La méthode d’évangélisation des Rédemptoristes belges au Bas-Congo: 1899-1919 : étude historico-analytique. Gregorian Biblical BookShop, 1999.

Reardon, Ruth Slade. “Catholics and Protestants in the Congo.” In Christianity in Tropical Africa: Studies Presented and Discussed at the Seventh International African Seminar, University of Ghana, April 1965, edited by International African Seminar, 83–100. London: published for the International African Institute by the Oxford UP, 1968.

Slade, Ruth M. King Leopold’s Congo; Aspects of the Development of Race Relations in the Congo Independent State. London, New York, Oxford University Press, 1962.

Van Reybrouck, David, and Isabelle Rosselin. Congo, une histoire. Arles: Actes Sud, 2012.

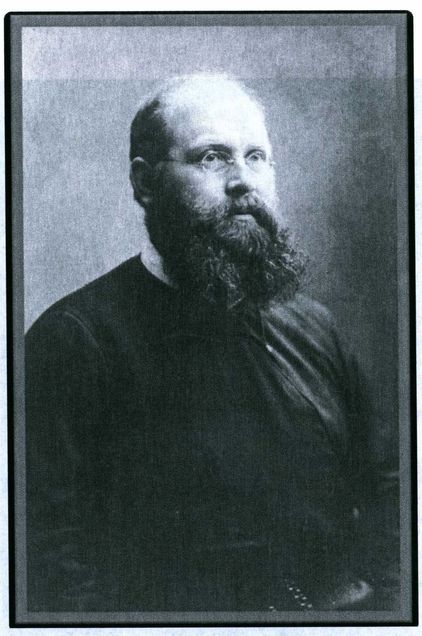

Portrait

From the Archives of the Province Belge Septentrionale de la Congrégation du Très Saint Rédempteur, reproduced on p. 782 of Bita Lihun Nzundu, Augustin. Missions catholiques et protestantes face au colonialisme et aux aspirations du peuple autochtone à l’autonomie et à l’indépendance politique au Congo Belge (1908-1960): effort de synthèse. Roma: Pontificia Università gregoriana, 2013.