Category: Uncategorized

The Real Thing

Russell Hornsby (’96) brings complexity and grace to his role in The Hate U Give

By Joel Brown | Photo by Benjo Arwas

Maverick Carter stops his SUV in front of his house and growls at his three children to “get out of the car and line up on the grass.” A confrontation with the police has ruined their family dinner out. His teenage daughter tearily blames herself for causing it by speaking up about the police shooting of a friend. In the 2018 film The Hate U Give, Maverick is an ex-con, ex-gangbanger, ex-drug slinger, a man with volatile emotions who seems ready to explode—but what he says to his children is unexpected: “Point 7 of the Black Panther 10-Point program! Stop crying and say it!”

The children gather themselves to repeat: “We want an immediate end to police brutality by any means necessary.”

Maverick leans in to tell them that some things are worth speaking up for: “Don’t ever let nobody make you be quiet!”

In most American movies, Maverick would have been absent or in jail or on the streets, says Russell Hornsby, who plays him in The Hate U Give. Maverick might come around to bicker with his wife, but he wouldn’t be much of a parent, a stereotype reflecting society’s distorted perception of black culture.

But in the film, based on Angie Thomas’ 2017 New York Times bestselling young-adult novel by the same name, Maverick is a store owner who has long steered clear of his old gang ties, a hard-edged but fully present family man determined to keep his kids safe in an America that seems hostile to their very survival.

“We’re saying now that we need to see a well-rounded image of who we are,” says Hornsby (’96). “The truth of the matter is, Maverick does exist. There are men who are felons and ex-cons who have come out and made good on their lives. And they do have families and they do have loved ones and they are present. And that’s what we needed to show.”

The 2018 film The Hate U Give is based on Angie Thomas’ 2017 New York Times bestselling young-adult novel by the same name. 20th Century Fox

Changing the conversation

For many years, a black ex-con with gang ties in an American movie was usually a powder keg certain to explode in violence; films depicting the civil rights struggle often had passive black characters menaced—and saved—by white characters. It was hard for African Americans to find their lives depicted authentically, in all their complexity, on-screen.

A change began, Hornsby says, with Spike Lee’s early films and a personal favorite, 1995’s Devil in a Blue Dress, directed by Carl Franklin, starring Denzel Washington and Don Cheadle. “That is one of the most authentically black films that you’ll ever see, in my opinion. We’re just living. We’re not struggling, and trying to overcome, and all this kind of sh-t. We’re just living. And you see the black world they live in, and how they talk, in their own world, where the cloud of The Man isn’t over them. That’s us, and it’s so beautiful.”

That kind of climate change may be accelerating for black filmmakers in the era of Black Lives Matter and a president seen as openly racist by many. Hornsby points to Moonlight (“beautiful and deeply honest”) and Get Out as recent films that treated black characters and black concerns authentically.

Many said the same of The Hate U Give. The movie, which was directed by George Tillman Jr. and written by the late Audrey Wells, garnered critical acclaim and honors, including the audience award at the 2018 American Film Festival and a Top 10 ranking from the African-American Film Critics Association. Hornsby’s performance earned him a best supporting actor award from that group, and enough award-season buzz that the New York Times did an interview, although an Oscar nomination didn’t materialize.

Amandla Stenberg plays Maverick’s teenage daughter, Starr, who attends an upscale, mostly white prep school and is the only witness when a white cop shoots an unarmed young black man. Her emerging activism throws her family into a maelstrom of controversy, pulling in the police, media, protestors, and the local drug lord. But instead of acting like the stereotypical hothead, Maverick stands by his daughter, even stays with her the night after the shooting, holding a bucket when she vomits, comforting her as best he can. He knows too well the aftermath of violence, but he is also a loving dad, and tells her the world needs her: “Shine your light.”

Maverick Carter (played by Russell Hornsby) explains to his young children what to do if they are ever stopped by the police. Erika Doss/Twentieth Century Fox

Drawing from life

To tap into Maverick’s complexity, Hornsby drew on his own upbringing. He grew up with a single mother in Oakland, Calif., “not always the safest and best place to live,” even though they weren’t in the toughest part of the city. When he wasn’t in school, he spent a lot of time at the Dimond Recreation Center, where a crew of older men on staff watched over the kids summer after summer.

“They were good guys, but gruff, they talked to you in a certain way that commanded respect,” he says. “They weren’t doing anything illegal, but they talked to the around-the-way cats, the drug dealers, whatever. But there were also moments when they had a different kind of compassion, when a little kid fell and scraped his knee, and they’d hold him and be like, ‘Don’t worry about it young man, we’ll clean you up and you’ll be back playing in no time.’ And then later, you’re older, and you hear them talking about how their wife’s having another baby and how are they going to pay the rent or feed this child. It humanized them.”

“In images, it’s important to strike racism a metaphorical blow, and i think that’s what maverick does. that’s what you do when you’re able to color a character in with dimension and nuance and grace notes.”

Russell Hornsby

In 1999, when he was in his mid-twenties, Hornsby played Youngblood in a production of August Wilson (Hon.’96)’s Jitney, one of a handful of the playwright’s works he has performed in. The other actors were mostly older black men with families and money problems and complicated personal histories. He learned as much from them offstage as on, listening to them talk about their struggles and burdens, failures and successes, how they kept going. “And I have to honor those men, because I heard their voices. Me playing Maverick, that’s me saluting them and saying thank you for helping me.”

Maverick reflects all these men, Hornsby says. “That’s why the movie is so important, because the larger part of society has not seen that image of black men. In images, it’s important to strike racism a metaphorical blow, and I think that’s what Maverick does. That’s what you do when you’re able to color a character in with dimension and nuance and grace notes.”

A deep dive into creating character

When he was a younger actor trying to make his way from the stage to Hollywood, Hornsby was mostly just thinking about getting work, but when he auditioned to play stereotypical thugs, he got rejected.

“I spoke proper English,” he says with mock regret, and Hollywood was hiring rappers for their real-life street cred. “‘No, he can’t be a ghetto guy, he’s too clean-cut, he talks clearly, he enunciates! He’s not black black, he’s just black.’”

He did get cast in 2005’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’, the 50 Cent movie, playing a henchman with gold teeth, but they cut a lot of his scenes.

Hornsby can play doctors, lawyers, and cops with the best of them, but Maverick was a responsibility as much as a role. Preparing to play him demanded a deep dive into the character. Benjo Arwas

In retrospect, the reverse stereotyping served him well by allowing him to play other things: a hospital chief resident when he was just 26, a cop with kids. In NBC’s fairy-tale-noir series Grimm, he was a tough cop helping his partner keep the peace between humanity and mythological creatures. And in February, he debuted on Fox’s Proven Innocent as a lawyer who gets series star Rachelle Lefevre out of jail after she’s wrongfully convicted of murder. They partner up to help others unjustly behind bars.

Hornsby can play doctors, lawyers, and cops with the best of them, but Maverick was a responsibility as much as a role. Preparing to play him demanded a deep dive into the character.

“I sequestered myself for a month because I wanted to imagine that solitude and confinement he had while he was in prison,” says Hornsby, who lives near Hollywood. “I asked my wife to take the kids, and she went to her mother’s for a month. My day consisted of getting up early, going to the gym, coming back and making a simple breakfast, reading and writing. I immersed myself in his world, because you have to create the character from the inside out. You write out who the character is, you write out his biography, the things he thinks about. It was taking time to walk around the city by myself and find his walk, his speech patterns. These are the details you have to get into. It’s about being honest and truthful about who he is.”

Hornsby talks with The Movie Times about how black men and black fatherhood are—and should be—portrayed on-screen. The Movie Times

It’s difficult to pull apart the threads of a performance, he says. But he offers an extraordinarily subtle example of how that preparation played out on-screen: watch Maverick walk, he says, when the family approaches the courthouse where Starr is going to testify about the police shooting. “You see the walk right there, and you see the way my hands form. They’re kind of open and they’re spread by my side. This openness. And the reason is, you’re in prison, you’re in a six-by-nine-foot cell, right? Your gait is smaller when you come out, because you’re so used to being in a confined space. So what Maverick had to do was relearn how to walk, and now there’s more freedom in the walk. He’s more expressive than he used to be, because he’s a free man. You’re in prison and you lose yourself because you’re confined, and you’ve got to find yourself again.”

Other roles have also required Hornsby to do the deep dive, like Lyons, the son of Denzel Washington’s character in the 2016 film adaptation of Wilson’s Fences, or grieving father Isaiah Butler in the well-received 2018 miniseries Seven Seconds. That preparation means that once he gets to the set he’s ready to work, to “drop in” to the character. “You get into the makeup trailer and then, boom.”

“I immersed myself in his world, because you have to create the character from the inside out.”

He’s gotten the best notices of his career in these parts. But film industry kudos aren’t what motivates him. “If you are waiting for somebody else to validate you, you are going to be waiting a long time,” he says. “I have had an objective career in a subjective industry, you can’t deny that, so just in that alone I am victorious.”

With Proven Innocent soon to finish shooting, he says, “I get to go back and sow some more work; 2017 was planting season and ’18 was the harvest, and now I have to go back to planting.” He’ll continue to look for roles that expand the way black men are defined on film, and he’s optimistic, to a point, that more such roles are becoming available.

“We’re no longer having our stories told or intercepted by the dominant culture,” Hornsby says. He sees The Hate U Give’s journey to the big screen as a turning point: in the past, a book by a black woman about her experiences and culture would not have been adapted “truthfully and honestly,” he says. “I think we’re having a renaissance in that people are having an opportunity to tell their stories in their way authentically.”

Saving the Classical Music Ecosystem

How music criticism and classical music adapt with the times to remain relevant

By Lara Ehrlich | Illustrations by Edward Carvalho-Monaghan

On November 14, 1943, Leonard Bernstein, then just 25, stepped in at the last minute to cover for the New York Philharmonic’s ailing conductor at Carnegie Hall. The concert was broadcast live on radio to millions of listeners, and was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. “Mr. Bernstein [Hon.’83] advanced to the podium with the unfeigned eagerness and communicative emotion of his years,” the Times critic wrote. Bernstein’s philharmonic debut was news, and the review catapulted him to fame.

In Bernstein’s day, classical music received almost as much coverage as professional sports. That was true into the late ’70s and ’80s, says Tony Beadle (’74), executive director of Rockport Music, who was performing double bass with the Boston Symphony at the time. “When you opened the Boston Globe on a Monday morning, three critics covered a lot of music in long articles, and their reactions were important to musicians,” he says.

Now, readers would be hard-pressed to find those stories in the popular press. Papers are trimming costs to compensate for plummeting profits, a trend that began in the ’80s. The arts section took the greatest hit, with classical music criticism as the first casualty.

Opera producer Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94); Anthony Tommasini (’82), the chief classical music critic for the New York Times; and Tony Beadle (’74), executive director of Rockport Music. Michal Fattal (Morrison); Earl Wilson/the New York Times (Tommasini); Courtesy of Tony Beadle

The decline of classical music’s visibility in the mainstream media is a blow to an art that’s struggling to draw audiences. Attendance, already lagging behind that of other performing arts, has been declining for decades. The National Endowment for the Arts reports 11.6 percent of adults in the United States attended a classical music performance in 2002. By 2017, that number had dropped to 8.6 percent.

CFA spoke to three experts—Beadle, Anthony Tommasini (’82), the chief classical music critic for the New York Times, and Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94), an opera producer known for mounting innovative new work—about how classical music criticism is changing, how those changes are transforming classical music, and the role, and responsibility, of the contemporary critic.

Slipping out of the mainstream

In the three years following the Great Recession of 2008, half of the arts journalism jobs in the US disappeared. And they’re not coming back. As newspapers have slimmed and folded, specialized art critics—those who cover genres like dance, theater, and classical music—have become arts generalists, been laid off, or moved to different beats. (In 2016, the San Jose Mercury News scrapped its classical music coverage and consigned its critic to covering real estate.) Only a very few specialists remain, and of those, “I can count the number of full-time classical music critics on both hands,” Douglas McLennan, the editor of ArtsJournal, told San Francisco Classical Voice.

Tommasini is one of these rarities. A trained pianist, he performed and taught music until switching to journalism; he’s been the chief classical music critic at the New York Times since 2000 and has written four books on music. With so few experts in classical music criticism, Tommasini and his handful of peers have become the voices of authority on the genre.

But they can’t possibly cover every concert or every new piece of music—and the choice of what to cover is constrained by the need to attract readers in an industry obsessed with clickbait.

“Reviews of concerts are minimal,” says Beadle. “Critics just don’t have the space and the time to write about a concert’s complexities, as they might have at one time.”

“I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.”

Beth Morrison

“This has done a terrible disservice to the classical music industry,” says Morrison, one of the most sought-after producers in the opera world and founder of the indie opera company Beth Morrison Projects. Morrison collaborates with composers to develop new works: she assembles the creative team; works with the artists to identify and implement the creative vision for the piece; secures the world premiere venue, funding, marketing, and publicity; and develops the pitch materials. Critical coverage of her projects is vital to their success and longevity, she says. “I worry very much about the next generation of artists and how they will fare with the decline in number of critics, as well as the number of words devoted to our art form in the various publications.”

It’s not just the word count that’s crippling classical music, says Beadle, who considers the biggest loss to be “articles about music in the mainstream; that’s what criticism was. Those reviewers brought not only last night’s concert to readers, but also the world of the musician and what they’re doing artistically.”

Amid the cutbacks, amateur critics have stepped in, putting more of an onus on readers to vet their sources. “You can find bloggers and critics writing on internet sites who are astute, informed, lively, and fair-minded, and you can find opinionated, untrustworthy know-it-alls,” Tommasini says. “Established journals and newspapers vouch for their critics and reporters and hold them to high standards. The internet challenges users in all fields to make their own determinations about the reliability of the voices they read.”

Beadle points to one internet source he finds reliable, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, billed as “a virtual journal and essential blog of the classical music scene in greater Boston” that features contributions from 80 musicians, composers, academics, and music aficionados.

“It’s harkening to the old days because writers have plenty of space” to take on the complexities of classical music, Beadle says. This kind of journalism is “a 21st-century answer to what has happened in classical music criticism.”

In this new wave of nonprofessional critics, Tommasini believes his voice is not only still relevant, but that “it matters more and more. When there’s so much chatter and so much writing out there about the arts, a trustworthy voice at a place like the Times cuts through.”

As newspapers have slimmed and folded, specialized art critics—those who cover genres like dance, theater, and classical music—have become arts generalists, been laid off, or moved to different beats. Now, “reviews of concerts are minimal,” says Beadle. “Critics just don’t have the space and the time to write about a concert’s complexities, as they might have at one time.”

He does his part to keep pace with a changing industry by incorporating multimedia to keep his readers engaged. In a 2017 review of Trinity Wall Street’s concert in honor of composer Lou Harrison, Tommasini included Spotify links to musical elements he wanted readers to appreciate; for instance, how “the slow second movement, a Siciliana in the form of a double canon, unfolds in skillfully written counterpoint. Yet the lines creep up and down and overlap with impish freedom.” Or, how “the aptly named Stampede movement races along like some combination of Asian dance and American hoedown.” Thanks to the web, readers can listen to 30-second snippets and hear for themselves what the critic is enthusing about.

Tommasini also embeds YouTube footage of concerts in his reviews, and films his own educational videos. He’s not alone in using the internet to his advantage; his fellow critics are also changing with the times to keep—and build—their readerships. Alex Ross, longtime music critic for the New Yorker, supplements his print criticism with his popular blog, The Rest Is Noise, in which he posts photos, videos, and music clips with brief commentary.

Tommasini doesn’t see the internet as a competitor, but as a complement to his work. The print and digital versions of the New York Times “go together,” he says. “You can read something on one or the other and have a rich experience, but ideally you look at both. That’s opened up all sorts of possibilities while also introducing challenges. It’s changed the way we do arts criticism.”

Tommasini still employs old-school techniques, like evocative writing, to engage readers as diverse as scholars, conductors, musicians—and people who’ve never seen a classical musical performance. He writes about music in a way that the general reader can understand, a tricky enterprise that some other beat writers don’t face. “The typical crowd at Yankee Stadium knows more insider information about baseball than the typical audience at the New York Philharmonic,” he says. “I envy sports writers tremendously for all the knowledge that they can assume their readers have.”

Plus, as he points out, “it’s very hard to describe sound in words. We have this handy technical language to do that, but only musicians know it. I can’t just use a term like chromatic harmony without losing readers.” His talent for describing music in vivid and accessible language is part of what has earned him a reputation for being “entertaining, highly enthusiastic, and very knowledgeable,” says Kirkus Reviews, “he’s the perfect guide.”

About a performance of Sibelius’ Fourth Symphony, Tommasini wrote that the second movement “sounds like a fractured dance in which the broken parts have been reassembled, but in the wrong way.” About a Leonard Bernstein performance of Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring”: the opening solo melody “slowly instigated a restless tangle of squirrelly lines that became a needling, nasal-toned free-for-all.” The goal is not just to engage readers, but to turn them into listeners.

“It’s complicated, because on the one hand, I’m here to inform people about music—but I also want people, especially young newcomers, to take a chance on a concert,” he says. “An opera or chamber music program is not an exam; you don’t have to take a music appreciation course first. Just go.”

The fragile ecosystem faces collapse

Despite the fact that their numbers are declining and their roles diminishing, critics still have an outsized impact, particularly when it comes to new works. “Most artists I know feel that the critics have an enormous amount of power; essentially, the power to make or break careers,” Morrison says. “At the same time, critics don’t have jobs without the artists they are hired to write about. With this interdependence comes responsibility. A media member should always be rooting for an artist’s success; without that, the ecosystem, which is already incredibly fragile, faces imminent collapse.”

Reviewing new work is “when a music critic can really matter, if a first performance is going to lead to a second, a third and a future for the piece,” Tommasini wrote in the New York Times. He takes that responsibility seriously, and he approaches new work with an open mind, suggesting that critics do a disservice to new music by coming to it with predetermined criteria for greatness.

His latest book, The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide (Penguin Press, 2018), is in part a meditation on greatness. “All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so,” he says. “We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming, so greatness can get in the way. We hold up the giants and compare new composers to them.”

“All the arts may be obsessed with greatness, but classical music may be too much so. We probably still remain the most conservative of the performing arts in terms of the ratio between new and old programming.”

Anthony Tommasini

“Imagine if you were teaching a short story workshop and young Franz Kafka showed up, with those very peculiar stories,” he wrote in the New York Times. “Would you chide him for some assault on language, or perhaps consider that he might be on to something strange and new and fascinating? If I err on the side of being open-minded in reviewing a new work, that’s O.K. by me.”

Organizations can help keep their industry alive by embracing new work, he says. That’s not such an easy task, as many classical music institutions are struggling to fill seats, especially in the absence of reviews that once sparked public excitement and spurred ticket sales, Beadle says. “They have to rethink their strategies.”

Musicians and orchestras are doing just that, by performing in nontraditional venues (the San Francisco Symphony hosts SoundBox, a concert series in a warehouse), experimenting with technology (the Boston Symphony Orchestra is loaning patrons iPads programmed with information about the performances), and adjusting ticket prices (the Cleveland Orchestra allows students to attend as many concerts as they’d like for $50 a season).

And many schools, like the School of Music at CFA, encourage musicians to seek creative ways to pursue their passion. For instance, CFA hosts an annual career development workshop series, which includes presentations on issues like freelancing, taxes for artists, financial literacy, and developing an online presence. Courses like Cultural Entrepreneurship and the Creative Economy and Social Impact promote entrepreneurship, and a minor in arts leadership gives students the opportunity to further develop their expertise.

Beadle believes classical music still holds plenty of promise. At music schools like Boston University Tanglewood Institute, he says, “you will see hundreds of kids playing classical instruments. And all the music schools are filled with students who want to play their instrument and excel at it.”

Those artists give critics something to write about—and ensure the relevance of music criticism. “Not only do artists contribute to the cultural and social richness of their community,” Tommasini wrote in the Times, “they make news. . . . A review is both an opinion column and a news report.

“But the most astute and simple defense of the role of the critic I know of came from (no surprise here) Virgil Thomson, [a composer-critic who] wrote that while traveling in Spain he was fascinated to see that it always took at least three children to play at bullfighting. One to be the bull, another to be the toreador, and a third to watch and shout ‘Olé!’ Music criticism is like that.”

Art at the Heart of BU

Artists work with unexpected canvases throughout campus

By Emily White

Photos by Bob O'Connor and Cydney Scott (Blue-Green Brainbow)

Sculptures, paintings, and multimedia works appear on walls, in windows, and along running tracks all across Boston University’s campus. Many are site-specific pieces, designed by artists who draw inspiration from the location and the surrounding environment and communities. Each site offers unique and often irregular canvases.

At BU a spectrum of academics, research, and technologies informs and inspires compelling site-specific artwork from a broad range of artists, including students and alumni. CFA professor of art Hugh O’Donnell and his students look for ways to bring together seemingly disparate areas of study: coding and sculpture, painting and fitness, biochemistry and printmaking.

“When combined with technology, art can do more than provide entertainment; it can rebuild and reanimate society,” says O’Donnell.

Featured here are six artworks either created by CFA students, alums, and faculty, or commissioned for the University—and where to find them.

Angular shapes layered with soothing gradients evoke a colossal, colorful stained-glass window in this mural on the wall of CFA’s parking lot at 855 Commonwealth Ave. Designed by Alexander Golob (’16), the mural conjures BU scenes, from the Citgo sign to Marsh Chapel. Golob was recently commissioned to install artwork expressing Innovate@BU’s vision statement in the University’s BUild Lab Student Innovation Center.

In 2017, sculptor and printmaker Carson Fox debuted her jaw-dropping 230-square-foot installation Blue-Green Brainbow in the lobby of the Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering at 610 Commonwealth Ave. Fox’s body of work evokes forms found in nature: coral, ice, and, in this case, neurons. Fox researched the work taking place inside the building to create an installation that referenced a pioneering neuroimaging technique—called Brainbow. The piece, which subtly morphs throughout the day as the light shifts across its many surfaces, is composed of 13,500 individually cast resin dots and took six 14-hour days to install. It captures “the beauty and wonder found in the life sciences,” Fox says.

In 2010, Rebecca Wasilewski (’07) designed a series of opaque panels for the lobby of StuVi-2 student housing. With an open-ended directive that the work should have an element of translucency, Wasilewski created hanging panes that allow light to filter through them in a soft glow, giving the effect of an inky, larger-than-life monoprint. The panels were designed for the space from the artist's print series Microscopium.

Another example of art inspired by scientific research is the luminous jellyfish by Heather Richard (’99), on the first floor of the Photonics Center at 8 St. Mary’s St. Noctiluna, which depicts a jellyfish that emits an ethereal light from a green fluorescent protein, was installed in 2000. The organic chemical reaction that produces the jellyfish’s light inspired Richard’s installation, commissioned with the challenge to create a work of art using light as a medium; the work evokes a traditional drypoint etching technique. The artwork was cut into acrylic glass, which emits light whenever it is scratched, and layered to imply a jellyfish submerged in water. Its light source comes from ultraviolet fluorescent lights positioned around the piece. At the time, BU School of Medicine professor Osamu Shimomura (Hon.’10) was studying the creature’s bioluminescent protein. Shimomura, who passed away in 2018, won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2008 for discovering the green fluorescent protein in jellyfish.

Public art at BU is integrated with the fabric of Boston. Students in CFA’s Site-Specific Art class noticed the eight sparse panels along the platforms at the BU West MBTA stop and decided to bring art to Green Line commuters. Andy Bell (’09), Seth Gadsden (’07), and Kristie Eden O’Donnell (’10) designed three projects that were installed in 2008 and 2009. In Bell’s panel for the BU West outbound stop overlooking the College of Fine Arts at 855 Commonwealth Ave., Rhett, the BU terrier, grapples with the Northeastern University husky mascot.

Josef Kristofoletti (’07) designed the vibrant mountain of sneakers, titled Sneakerman, on the wall of the indoor running track at the BU Fitness & Recreation Center when he was a painting student at CFA. Kristofoletti went on to become an artist-in-residence at CERN in Switzerland. There, he designed a three-story mural depicting the ATLAS particle detector, which is collecting data at the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

A Language of Time and Space

Sculptor Won Ju Lim draws on architecture to create futuristic, cinematic worlds

By Mara Sassoon | Photo by Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

Won Ju Lim says her work is never really complete; her multimedia installations are altered in unexpected ways whenever they move to a new place. “The architectural location—the space, the height of the ceiling, the geographic location, the lighting—these factors all make a difference,” says Lim, an assistant professor of sculpture at CFA. Mutability is essential to her work, which explores the relationships between people, objects, space, and time.

One of the pieces that has morphed as it’s been displayed in different venues is California Dreamin’ (2002/2018), which Lim created while living in Germany and feeling homesick for Los Angeles, where she grew up. The piece is comprised of more than 100 luminous plexiglass and foam-core board structures in shades of blue, green, and yellow that look like stacked Tetris pieces. Lim based the structures on floor plans from old do-it-yourself home catalogs. The installation also incorporates videos and still image projections of distinctive California scenery: palm trees, sunsets, boxy architecture.

California Dreamin’, 2002/2018. Plexiglass, foam-core board, lamps, three video projections. Exhibition view at San José Museum of Art. Photo by Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

First shown in 2002, the installation was recently acquired by the San José Museum of Art (SJMA), where it was the centerpiece of the 2018 exhibition Won Ju Lim: California Dreamin’. There, the piece took on new meaning: it had returned to its geographic roots, transforming a dreamscape influenced by homesickness into an idyllic vision of Hollywood. California Dreamin’ was installed in a vast, dimly lit room, where its structures were amassed into an island, their jewel tones picking up light from three videos projected on the gallery walls. The island motif was inspired in part by Lim’s interest in the origins of her home state’s name, which can be traced to the fantastical 1510 Spanish chivalric romance novel Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. The state was named after the book’s paradisiacal island made of gold and its ruler, Queen Calafia, Lim says.

California Dreamin’ was also heavily influenced by the style of science fiction films like Blade Runner and Metropolis. “The aesthetics of the cityscapes shown in these films are from decades ago, yet they remain futuristic; they suggest a superimposition of the future and the past, suspending the present,” Lim says. Cast in the cinematic glow of the surrounding videos, California Dreamin’ could be a set model for one of those films.

“My ambition was, and still is, to carry on my interest and knowledge in architecture without the confinements and limitations architects often confront.”

Won Ju Lim

Lim’s background in architecture is palpable in many of her works. Born in South Korea, she earned a BS in architecture from Woodbury University in Burbank, Calif., and an MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, and worked at architectural and design firms prior to becoming a studio artist.

“The issue of practicality inherent in architecture can be explored and questioned in making art,” she says. “My ambition was, and still is, to carry on my interest and knowledge in architecture without the confinements and limitations architects often confront.

“As an artist, I do not feel obligated to answer or solve practical issues concerning space, but I do feel the need to expose and explore our psychological and phenomenological relationships to space.” She does this by playing with scale, focusing on interior and exterior relationships, and considering the interactions between people and her art.

Her mixed media sculpture A Piece of Echo Park (2007), for example, which was on display in the California Dreamin’ exhibition, is a miniature topographic model of a hilly formation dotted with tiny trees and houses, contained inside a yellow plexiglass box. One side of the sculpture is covered in what looks like grass and shrubs, the other side reveals exposed plaster patchily covered in splotches of neon pink, green, and orange paint. By containing the structure in a bright yellow box, Lim places the viewer on the outside looking in at this diminutive world.

Lim’s Kiss 7 (2005) contains plexiglass models of the Los Angeles Case Study Houses (experimental homes built by renowned architects in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s) in wall-mounted boxes. Kiss 7 highlights a sense of changeability; any variation in light or human interference alters the installation.

For her current project, Aunt Clara’s Dilemma, Lim was inspired by the way characters travel through space in the television show Bewitched. She became fascinated with the way the witches in the ’60s sitcom pass through doors and walls, and is particularly intrigued by Aunt Clara, an elderly witch whose powers become increasingly erratic.

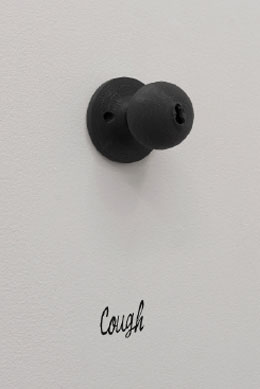

“Unable to clear the hurdle of the door, Aunt Clara becomes a fetishistic collector of doorknobs,” Lim says.

Aunt Clara’s Dilemma is composed of 3-D-printed doorknobs twisted into animated representations of bodily functions; one is evocative of a sneeze, another a cough. Lim plays off of Aunt Clara’s obsession and imbues the doorknobs with human characteristics to represent the division of space and how people move from one place to another within it.

“Space is a word that makes something of the nothing that surrounds us,” Lim says in her artist statement about the piece. “I see Aunt Clara’s Dilemma as a body of work about doorknobs, thresholds, and the moment when the old dialectic of outsides and insides becomes a mise-en-abyme,” embedding a copy of an image inside the image itself (such as a portrait of an artist holding that same portrait).

With Aunt Clara’s Dilemma, as in all of her installations, Lim says, “tangible things such as plexiglass, wood, and resin are merely vehicles that carry a specific language of time and space.”

Kiss 7, 2005. Plexiglass, lamp, shadow, 7 x 24 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

Kiss 4, 2007. Plexiglass, lamp, shadow, 7 x 60 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

Memory Palace, Terrace 49 #1, 2003. Anodized aluminum box, frosted Mylar, LED lights, mixed media sculpture, 42 x 42 x 20 inches. Courtesy of Won Ju Lim

A Piece of Echo Park, 2007. Mixed media sculpture in plexiglass box,

38 x 45 x 38 inches. Exhibition view at San José Museum of Art. Johnna Arnold/JKA Photography

Cough, 2018. 3-D-printed object in styrene, vinyl lettering, 3.5 x 3 x 3 inches. DXIX Projects, Venice Beach, Calif.

Sneeze, 2018. 3-D-printed object in styrene, vinyl lettering, 3.5 x 3 x 3 inches. DXIX Projects, Venice Beach, Calif.

Master Class

By Rachel Johnson | Photo by Oshin Gregorian

“I fell into the world of opera,” says David Kneuss (’70), executive stage director of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Although he began his professional life as an actor, the School of Theatre graduate quickly moved into directing, staging hundreds of operas around the world during his 35-year career. In 2012-2013, he returned to CFA for two residencies in the Opera Institute.

David Kneuss (’70) staged the first two acts of the Marriage of Figaro with tag-team casts. Photo by Oshin Gregorian

What was your favorite residency moment?

We staged the first two acts of the Marriage of Figaro with tag-team casts—starting with one group of singers and then trading off to another—so I was able to work with a number of students. One of our Counts was a wonderful bass baritone, and in the second act, he switched to playing Antonio, the drunk gardener. This student was very refined and careful. The day of the performance, I told him to come in with a mouthful of crackers and blurt out his lines. He walked onstage and opened his mouth, and crackers flew all over the place. Nobody was expecting it—and it was perfect. I need to be just a little outrageous with these students to get them out of their comfort zones.

You regularly stage operas in Japan. How are Japanese and US audiences different?

Japanese audiences are very polite. They don’t applaud until the end, when they go completely crazy. They’re very serious and knowledgeable about opera, and they almost never go to see an opera for the first time without having listened to it first. It’s quite thrilling.

Does education help audiences appreciate opera?

You could go to an elementary school in Japan, and every kid is playing the violin. Japan figured out that learning music helps you learn other things. And I think it becomes very obvious when you compare their tremendous emphasis on musical education to the deterioration of music education in this country.

“In this social media world, things have to be instantaneous. There’s nothing instantaneous about opera...I think once we get an audience in the seats, though, they’re usually pretty happy with the show.”—David Kneuss

How has opera changed in the last 35 years?

It’s harder to get an audience now. When I first came to the Met, we never had to buy ads and the opera was still 97 percent sold-out every night. Now we spend a lot of money on publicity and we struggle to fill the seats. They say it’s because the graying population of opera-goers is dying off. But you know, there are always more people getting gray; it’s just that priorities change. I think they change because there’s not much music education in schools, and in this social media world, things have to be instantaneous. There’s nothing instantaneous about opera. It takes an attention span that people don’t seem to have as much anymore. I think once we get an audience in the seats, though, they’re usually pretty happy with the show.

Was there a moment with opera when you thought, “This is why I wanted to do this”?

The first production I worked on was a live telecast of Tosca, with Luciano Pavarotti and Shirley Verrett. It was my first job as assistant director, the director left, I was suddenly in charge, and we were sending this television show out live to the world. I remember walking home afterward thinking I’d landed on the moon. I found out later that more people saw that telecast than had ever seen the opera before in history. That was a defining moment.

School of Music Gives Rhythm to Boston Symphony

The percussion section of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is also the BU division. Three percussion alums—Dan Bauch (’04), Kyle Brightwell (’12), and Matthew McKay (’11)—are members of the section, under the leadership of BSO Principal Timpanist and CFA Lecturer Tim Genis. “Our percussion department is widely known for having an exceptional work ethic and for its tradition of excellence,” says Richard Cornell, School of Music director ad interim. “The long history of deep connection to the Boston Symphony has been essential to our program.” BU’s commitment to excellence in percussion was highlighted recently with the opening of the Judith R. Harris Center for Music Teaching & Learning on CFA’s ground floor, which features a suite dedicated to percussion teaching and practice.—Rachel Johnson

CFA Trends on Twitter

By Lara Ehrlich | Photo by iStock/Ed Stock

Ginnifer Goodwin (’01)—Snow White on the hit ABC show Once Upon a Time—tweeted the celebratory message:

“So proud to have my alma mater @BU_Tweets named as one of @backstage’s Tried-&-True Acting Colleges! Go Terriers!”

In an article naming Boston University one of the “5 Tried-and-True Acting Colleges” in the United States, the renowned performing arts magazine Backstage commended the University for pushing “actors to be part of a play as well as understand the role their play takes on in a larger discussion.” Backstage lauded School of Theatre Director Jim Petosa’s philosophy that theater is “a force for understanding aspects of humanity, whether at the geopolitical level or at the local level. We’re not bound to one style or method, but we do tend to stress plays that really have an impact on our understanding of societal phenomenon.”

BU is in the company of Carnegie Mellon University; Rutgers University; the University of California, Los Angeles; and the Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.