Category: Uncategorized

Rick Heinrichs’ Magical Worlds

The production designer and CFA alum has overseen the creation of some of cinema’s most iconic places, from Gotham City to Halloween Town to a galaxy far, far away

By Marc Chalufour | Photo by Patrick Strattner

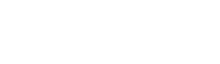

Heinrichs created this model of Jack Skellington, the protagonist of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. © Disney

Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas is a deeply macabre film. The star, a tuxedoed skeleton, has no eyes. His love interest tears her limbs off and sews them back on. A gang of trick-or-treaters kidnaps Santa Claus. A teddy bear gets dissected. Disney, concerned the creepiness wasn’t appropriate for its child-friendly brand, released the film under a different studio banner.

But the late film critic Roger Ebert saw magic. “The movies can create entirely new worlds for us, but that is one of their rarest gifts. More often, directors go for realism,” he wrote in 1993. “One of [Nightmare’s] many pleasures…is that there is not a single recognizable landscape within it. Everything looks strange and haunting.”

Though the film was created by Tim Burton and directed by Henry Selick, visual consultant Rick Heinrichs was critical to creating the immersive world of Nightmare’s Halloween Town. He translated Burton’s sketches into the first sculpture of the film’s protagonist, Jack Skellington, and was a visual consultant throughout production, helping to make Halloween Town a cohesive and believable setting for the stop-motion animated feature. The pair have partnered on 11 feature films—often with Burton directing and Heinrichs (’76) in charge of art direction or production design—including Edward Scissorhands (1990), Batman Returns (1992), and Sleepy Hollow (1999), for which Heinrichs won an Academy Award.

Over the past two years, he has helped filmmakers create J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth for The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (Heinrichs helped launch the series, then departed) and transform a Grecian island into the set of a murder mystery for Knives Out 2—both scheduled for release this year. Heinrichs’ credits also include work on some of the most memorable worlds in film, including Star Wars (Star Wars: The Last Jedi) and Marvel (Captain America: The First Avenger).

“My fascination has always been the creation of an environment and trying to instill it with expressive quality and emotional content,” Heinrichs says. Few in Hollywood have been as successful. After working his way up through the art departments on both animated and live-action films, Heinrichs has become one of the most sought-after production designers in the business.

Heinrichs first collaborated with Tim Burton on the short film Vincent, about a young boy obsessed with horror actor Vincent Price. © 1982 Disney

HOLDING THE FABRIC TOGETHER

A production designer guides a project’s transformation, from an idea to a three-dimensional world filled with actors, sets, costumes, and lighting. Done well, the result can immerse audiences in a fantasy world. The job requires a photographer’s eye, a sculptor’s hands, and a painter’s sense of color. The more fantastical the world, the greater the challenge in making it believable. “The writers, directors, producers, and actors—it’s pretty easy to figure out who does what,” Heinrichs says. “The rest of a film’s credits are a little bit harder to understand. They’re not directly related to getting butts in the seats. Our contributions are more diffusely woven into the fabric of the film itself.” The production designer must make sure that fabric holds together.

“With Tim, and with all of the other filmmakers I’ve worked with, it’s always been about the director and their vision,” Heinrichs says. “It’s just so powerful, seeing something which coheres around a vision that’s propelled by the storytelling of the director.” And Heinrichs has worked with some of the best, such as Terry Gilliam, Ang Lee, and Joel and Ethan Coen.

ANIMATED DREAMS

An annotated sketch and sculpture Heinrichs created of Nightmare character Sally. © Disney

As a kid, Heinrichs loved films, especially Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons. Art became an escape from the rigid structure of school. “When I was, like, 10, I would draw these imaginary projects with situational themes—like a haunted house where every room had a horrible murder going on in it,” he says. “I think my parents were both amused and concerned.”

Heinrichs wanted to study animation in college, but there weren’t many programs available in the mid-1970s. He opted for a broad background in fine arts. “I spent my late teens and early 20s getting my hands dirty in drawing and painting and sculpture, graphic design, printmaking,” he says. He appreciates how that background continues to benefit his work. “You gain some mastery over depicting the human form in light—that’s a discipline you can apply to many other things.”

By the time Heinrichs graduated, animation programs were beginning to pop up—including one at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where a number of Disney animators taught. “There was this whole group of like-minded individuals there,” he says. He met Brad Bird, John Lasseter, and John Musker (if you’ve watched a Disney or Pixar film in the past 35 years, you’re familiar with their work). He also met Tim Burton.

The two worked together on Disney’s 1981 film The Fox and the Hound, where they were responsible for drawing inbetweens—repetitive frames that create the illusion of motion following an animator’s key frame. “It was a bit depressing,” Heinrichs says. “You go to school and you’re told how amazingly inventive and creative you are—then you’re on an assembly line.”

While Disney didn’t wind up using Burton’s quirky, gothic sketches for their next project, The Black Cauldron, Heinrichs was inspired and began to sculpt the characters in three dimensions. “I thought they were very dimensional, but had that wonderful aspect of being very graphic and expressive at the same time,” he says. “In the work I’ve done with Tim, it’s turning graphic work into a kind of immersive world.” Their first film was the 1982 stop-motion animation short Vincent, based on a Burton poem.

The six-minute film tells the story of a young boy obsessed with horror actor Vincent Price. It’s dark and brooding and immediately identifiable as a Tim Burton work, with quirky characters and off-kilter structures.

A few years later, the two were sharing a studio in Pasadena when Burton began sketching scenes from a holiday poem he had written. “I saw this one drawing and almost immediately did a sculpture of Jack [Skellington],” Heinrichs says. He showed it to a stop-motion armature builder, who told him the legs were too thin. “So, I beefed everything up a little bit until he agreed he could make it. It was designed by everybody,” Heinrichs says. “As a result, you’ve got something never quite seen before, and that was a big part of the appeal. I want to work on a movie with other people. The fun is collaborating with them and coming up with something bigger than I could come up with on my own.”

Heinrichs won the Academy Award for Best Production Design for Sleepy Hollow. He created this sketch of the titular town (above). Courtesy of Rick Heinrichs (sketch); Entertainment Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo

EXPANDING THE GALAXY

While Burton’s films tend to occupy a world that is distinctively his, an increasing number of movies build upon existing fictional universes. Sequels, prequels, and reboots are big business, and Heinrichs has helped design some of the biggest—none more prominent than 2017’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi.

Heinrichs spent days in the Lucasfilm archives to prepare. He studied sketches and paintings done by the late Ralph McQuarrie, the conceptual artist who helped define the look of the original Star Wars trilogy in the 1970s and 1980s. “There’s a very identifiable look to the world he created. A simplicity of shape and color and lighting. It felt very modern and futuristic—but also weirdly retro at the same time,” Heinrichs says. His job was to carry that inspiration through a project that included 125 soundstage sets and locations in four countries. “That was the thing that was most exciting—coming up with elements that felt familiar and yet futuristic and cool.”

One of the film’s signature scenes unfolds on the planet Crait. It’s a classic Star Wars battle—good taking on evil against the backdrop of a unique landscape. Rickety Resistance ski speeders charge toward a menacing line of First Order AT-M6 Walkers. Laser blasts and shrapnel slice into the white mineral crust of Crait’s surface, sending red soil exploding into the air. The planet seems to bleed. The scene is reminiscent of the snowy battle on Hoth at the beginning of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, but it also recalls a moment from another Heinrichs film: the blood-covered snow in Fargo’s infamous woodchipper scene.

Heinrichs values his CFA education and the way it helps him interpret a range of artistic influences. For Captain America: The First Avenger, he had decades of Marvel comics to draw on, as well as World War II photographs and propaganda. The challenge, he says, was “the idea of visually presenting this confrontation between fascism and democracy—what are the colors and the shapes that attend to those opposing forces?” For the 2019 live-action adaptation of Dumbo—another Burton collaboration—he cites the painter Edward Hopper as an inspiration. “Understanding how he paints and composes his designs—those things live in your head and they combine with other ideas, and they ultimately come out in a completely different form as design ideas for film.”

Heinrichs also worked with Burton on the 2019 live-action adaptation of Dumbo. © 2019 Disney

YOUNG AT HEART

As formative as BU, CalArts, and Disney were, it’s been his ability to hold on to his childhood passion for creating that continues to fuel Heinrichs. “Nothing compares to your first discoveries and explorations as a kid,” he says. “Tim [Burton] would say that everybody’s an artist when they’re six years old. There is a purity and naïveté and passion to the work you do then. And he would joke, ‘It just gets beaten out of you over time.’” For the partners, success is avoiding that fate.

Heinrichs served as a production designer on the upcoming Amazon Prime Video series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. Watch a teaser trailer here. Video courtesy of Prime Video

Heinrichs can’t say much about his latest projects, Knives Out 2 and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power—both are in postproduction and scheduled for release later this year—but he continues to revel in world building. “It’s difficult to explain to other people how amazing it is to walk onto the sets and see what you’ve been imagining,” Heinrichs says. “It’s one of the reasons I love what I do.”

HEINRICHS’ HIGHLIGHTS

Rick Heinrichs got his start as an animation artist at Disney, but his big break came when he and Tim Burton produced a stop-motion animated short, Vincent, in 1982. The pair have since collaborated on 11 feature films. Heinrichs has worked his way up the creative ranks on both animated and live-action movies, and his design work and direction have enhanced some of the most memorable worlds in film. Here are some of the films that define Heinrichs’ career.

- Vincent (Short, 1982) • Producer, designer, sculptor

- Hansel and Gretel (TV movie, 1983) • Producer, model sculptor

- Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) • Animator, animated effects supervisor

- Beetlejuice (1988) • Visual effects consultant

- Ghostbusters II (1989) • Set designer

- Edward Scissorhands (1990) • Set designer

- Batman Returns (1992) • Art director

- Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) • Visual consultant

- Fargo (1996) • Production designer

- Sleepy Hollow (1999) • Production designer, Academy Award winner for production design

- A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004) • Production designer, Academy Award nominee for art direction

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006) • Production designer, Academy Award nominee for art direction

- Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) • Production designer

- Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) • Production designer

- Dumbo (2019) • Production designer

- The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (TV series, 2022) • Production designer

- Knives Out 2 (2022) • Production designer

A Bridge Between Cultures

A traditional Chinese instrument becomes a bridge between cultures

By Rich Barlow | Photo by citybrabus/Shutterstock

Wenzhuo Zhang was extremely young when she took up an extremely old musical instrument. At the impressionable age of five, Zhang (’15) attended an after-school music program in China’s Hebei province, where choosing from among the dazzling array of instruments stumped her. A kind instructor suggested, “Would you like to try the yangqin? I could teach you.”

She started lessons on the instrument, a stringed dulcimer played with bamboo beaters that dates to the 17th century. What began as a hobby has become a vocation for Zhang, who today teaches the yangqin and has performed in recitals from New York State, where she lives, to the UK. In 2008, she won the National Hammered Dulcimer Championship in Kansas.

Watch Zhang perform on the yangqin as part of the Rochester, N.Y., Memorial Art Gallery's Asian Pacific American Heritage Virtual Celebration in May 2021. Video courtesy of MAG Rochester

To Zhang, the yangqin is more than a music-maker. It’s a modern bridge-builder between different peoples, which is why she tries to pass on her mastery through teaching.

“Musical instruments are a form of cultural legacy and heritage,” she says. “Learning instruments or songs is one of the most efficient ways to learn the tradition of the cultural groups from which instruments and songs originated.” The yangqin is multiculturalism in wood and string: it was modeled on a Persian instrument and reached China through trade with the Middle East.

At 13, Zhang was admitted to Hebei’s competitive art school, which accepted only one student for each Chinese instrument every two years. After graduation, she enrolled in the prestigious National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts, then came to the US for a master’s at the State University of New York at Fredonia. She received her doctorate in music education at BU.

She teaches at SUNY Fredonia and has performed with a Chinese string and wind ensemble, Western ensembles, and Chinese folk singers, and in national and global recitals. Zhang says of her musical career: “When I think about the past, I realize that it wasn’t just my decision. It was my teachers’ decisions as well. They chose me, and I am grateful. I enjoy being a performer.”

Zhang says her studies, along with playing the yangqin, have shown her the importance of multicultural music education. She vows that she’ll “continue contributing to multicultural music education in research and practice, one of my everlasting career goals.”

Conversation: Emily Deschanel & Daria Polatin

Emily Deschanel ('98), left, and Daria Polatin (’00).

Actor Emily Deschanel and screenwriter Daria Polatin talk about collaborating on the Netflix limited series Devil in Ohio

By Mara Sassoon | Photos by Ben Trivett (Deschanel) and Patrick Strattner (Polatin)

In Daria Polatin’s debut YA thriller, Devil in Ohio, teenager Mae escapes from a satanic cult and moves in with her psychiatrist, Suzanne Mathis. Mae is supposed to live with Mathis and her family for only a few days, but her stay turns longer and longer—to the dismay of Mathis’ 15-year-old daughter, Jules. Mae starts wearing Jules’ clothes, attending her school, and dating her crush. Then, the cult attempts to get Mae back, putting the Mathis family in danger.

The 2017 book is inspired by real-life events. Polatin’s manager, producer Rachel Miller, brought the story to her attention, and she was riveted by the dynamics at play between patient and psychiatrist. “I thought, ‘I need to tell this story,’” says Polatin (’00), an accomplished playwright and screenwriter who has written for Amazon’s Hunters and Jack Ryan. She tracked down and interviewed a source closely involved in the incident and began writing. “A novel seemed like the best format to tell the story initially,” she says. “Novel writing and TV writing are very different. Novel writing can be very interior—you can really live inside the head of the character. But I always had it in the back of my mind to also adapt it for the screen one day.”

In 2019, Polatin began working on a pilot script in earnest. Later this year, Devil in Ohio, a limited series starring Emily Deschanel as Mathis, will begin streaming on Netflix. Polatin, the showrunner and executive producer, and Deschanel (’98), known for her role as forensic anthropologist Temperance “Bones” Brennan on the long-running Fox series Bones, go way back. Both studied acting at BU and quickly became friends while in the program. They reconnected over Zoom in January, just as Devil in Ohio was in postproduction, to discuss their memories of BU, what it’s like playing a man onstage, and how actors and screenwriters can work together to produce great film and TV.

Daria Polatin: Emily, remember when we were in A Tale of Two Cities together at BU?

Emily Deschanel: Yes, how could I forget? Wait, who was the British woman who directed that?

DP: It was Caroline Eves.

ED: Oh my gosh, you have a great memory. I think Caroline Eves directed that junior year Shakespeare project. Was she doing that when you were a junior?

DP: Yeah, I loved the Shakespeare project. It was basically making a new piece by taking story lines from different Shakespeare plays.

ED: Yeah, it was a Shakespeare patchwork quilt kind of thing. And I think it gave the opportunity for women to play a variety of roles. I think we probably both played men quite a bit in college…

DP: Because we’re tall! Yes, I played a lot of men in college.

ED: What men did you play?

DP: I played Guildenstern. We also adapted the book The Awakening by Kate Chopin, and I played the lead woman’s husband—walking stick and all. I can’t remember what else at the moment, but it was definitely a thing.

ED: Oh, that’s fun. Yeah, you played men more than I did. But, you’re how tall?

DP: I’m six feet.

ED: And I’m five-foot-eight. I think I was in an all-female cast in a production of Mrs. Warren’s Profession, but we all played men at some point in that. Such is the experience of a theater student.

DP: I liked it because it was almost easier to dive into something so different. I also liked playing characters with dialects or accents. It helped me embody something different.

ED: I totally agree. It’s fun to dive into a role with a different dialect or accent, or different physical qualities. I don’t get to do that as much now. I mean, I’ve done dialects, but it’s not like in college when it was like, you will play an 80-year-old man with a limp from Austria.

DP: It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period—to get to explore all different kinds of characters and play all kinds of roles without any pigeonholing or judgments. I really loved how intensive it was.

"It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period."

ED: I also loved the intensity of the program. We were in class from early in the morning through rehearsals late at night. For most of us, this was all we wanted to do. And I guess it prepared us for working in television.

DP: One hundred percent. It prepared us for 18-hour days.

ED: Except it’s a lot easier when you’re 20. Daria, you had told me that [the late CFA professor of playwriting Jon] Lipsky’s class was one thing that made you interested in writing. I want to hear what that experience was like.

DP: He had seen some of my work, and [during] my senior year at BU, he found me in the hallway and said, “You are a writer, and you need to take my playwriting class.” I enrolled, but almost dropped the class because I was so busy. I filled out my drop form and brought it to Lipsky. And I remember he said, “I’m not signing that.” I begrudgingly finished the play, an adaptation of Chekhov’s short story The Lady with the Pet Dog, turned it in, and the school ended up producing it for the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival. It won the regional contest, and then it was performed at the Kennedy Center and got published.

ED: Wow, that’s so interesting to hear. And to think if Jon Lipsky wasn’t your teacher. For the record, I took his playwriting class, and he did not tell me that I am a writer.

DP: Well, I’m glad to know he didn’t just say that to everybody and I just fell for it. [Laughs.]

ED: Do you miss acting at all?

DP: The last play I was in was an Off-Broadway production in the Summer Play Festival. I played an Italian actress/model with this great accent. It was so fun. But after that I was like, “I’m done.” I haven’t really looked back. Acting onstage made me very nervous. There’s no net—if you forget your lines, what do you do? I enjoyed it, but it gave me a lot of anxiety. Not that writing doesn’t give me a lot of anxiety.

ED: It’s funny because those kind of moments—being onstage or on set and you forget a line or someone else forgets a line, and you don’t know what to do next—they terrify the hell out of me, but they are also some of my most favorite moments in acting. It’s this crazy thrill of anything could happen. I thrive on that. I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it.

DP: Well, you’re very good at it. How did you find transitioning from mostly doing theater in school and then moving into TV and film?

ED: I didn’t have that transition some people have where they’re in New York doing theater first, even though theater was my first love. But I realized that there were so many more opportunities for me as an actor in LA. I found a manager in LA and then I started auditioning for film and TV roles. A few months later, I got my first job, a Stephen King miniseries called Rose Red. Scary stuff. I actually still use some of the script analysis things we learned at BU, and I think it’s helpful to have the background I got from BU to play different parts.

DP: The script analysis classes were so good at BU. I learned so much about storytelling and breaking down a story. I think what that gave me as a writer are the tools to know the kind of information the actor needs—the character’s motivations, backstory.

ED: Yeah, and us actors appreciate that. You can make lines work, but when you have the background to understand why you’re saying what you’re saying, it makes a huge difference. I’m thinking of our time on set. I got as much information as I could from you, both on the real story and your novel. I feel like I was always hounding you to give me more and more information. What was it like making your own book into a TV series?

DP: I have adapted other books for TV before. I worked on Jack Ryan for two seasons and the season of Castle Rock that adapted Misery and tells the Annie Wilkes backstory. But getting to adapt my own novel was so interesting. I just knew the characters and the world so intimately. For the TV version, we really wanted to go into it primarily through Suzanne’s eyes and experience the story from Suzanne’s perspective. Why does Suzanne take this girl home? Why does she want to help her?

ED: I found that fascinating too. It was really helpful that you had so much time with the characters and the story from writing the book and writing the series.

"I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it."

DP: When you’re storytelling, it’s not only about what you’re showing, it’s also about what you’re not showing. So knowing what you’re not showing is helpful and adds that extra layer to creating well-formed characters whose world you’re just happening to get a glimpse into certain parts of.

ED: That’s a good point. There are always things the audience is not seeing. That’s so interesting to think about. Do you want to write another novel?

DP: I do. But novel writing is extremely time-consuming, and I’m always thinking about what medium is best for a story.

ED: A novel is no joke. I mean, not that TV writing is an easy feat in any way.

DP: It’s all very time-consuming. It just takes so much physical and mental energy when you’re really giving your all to a project. You spend years working on these things, so it has to be something that continues to bring you joy and be interesting. I first started the pilot with Netflix, like, three years ago at this point.

ED: And when did you start writing the novel?

DP: I think in 2013. The novel came out in 2017. All in all, with the show coming out, it’s been almost a 10-year process that the story has lived through.

ED: I think it’s interesting for people to understand how long some of these things can take. That’s not always the case. Most of my career was in network series. So it was grind, grind, grind. Sometimes I’d finish an episode and it would air, like, two weeks later.

DP: Oh wow! One of the advantages to writing a show for a streaming service is that usually you will finish writing the season before you film it. Of course, there are always things that you learn on set, and you still have to pivot for all the production issues, like weather…

ED: Weather? What? [Laughs.] Yeah, we definitely had to deal with our share of weather in Vancouver while shooting Devil in Ohio. Some bomb cyclones, atmospheric rivers…

DP: Snowstorms.

ED: That was nerve-racking when it snowed because it wasn’t going to match what had already been shot, and there were these consecutive things that we had to shoot.

DP: Yeah, we had to heat blast an entire field to get rid of the snow. It was a fast shoot.

ED: It was so great to have this shorthand with you on set, Daria. It was like, okay, we know each other. Let’s just dive into the work part.

DP: And you brought such a beautiful, intense focus to this role, and really graceful empathy to this character.

ED: Thank you. That’s very kind. It was really lovely to work together after so many years in such a different way than doing A Tale of Two Cities at BU.

DP: We’ve come a long way since A Tale of Two Cities.

Inside the Industry with Kat Irannejad

Kat Irannejad (’97) helps run a top women-owned creative agency. Portraits of Irannejad were created by illustrators Steph Ramplin (left) and Dennis Eriksson, clients of Irannejad’s.

By Emily White Holmes

The visual arts have been a big part of Kat Irannejad’s life ever since she was a young girl and discovered she loved to paint. That love of painting set her on a path to her dream role: illustration agent.

After Irannejad (’97) earned her bachelor’s degree in painting at BU and an MFA in painting and art history at Pratt Institute, she worked in arts administration at the Smithsonian American Art Museum before taking on an array of jobs: photo editor at the New York Observer, where she worked with legendary illustrators like Barry Blitt; illustrations editor for a few National Geographic books; and artist rep at a British illustration agency. During that time, she found her true passion: connecting artists with clients to help produce spectacular publications, advertisements, and products.

As an illustration agent, Irannejad calls on the skills she learned in previous jobs, as well as her early experience as a painter: “I found that it has made a difference that clients know I come from a background where I do understand all the references they make. If they say, ‘We’re looking for an artist with a Robert Longo vibe,’ I get it.” In 2013, Irannejad and fellow artist rep Kristina Snyder cofounded the illustration agency SNYDER (formerly Snyder New York).

“It brings me genuine joy finding great talent and pairing them up with the world’s best brands—getting their work in the New York Times, on book covers, seeing their work in airports, in malls, on billboards,” she says. Here, she shares a couple insights she’s learned since starting SNYDER.

Select work by Irannejad's clients. Courtesy of SNYDER and, from left, Made Up Studio for The Washington Post, Aurelia Durand, and Ben Fearnley

Unapologetically stick to your ethos.

In a largely male-dominated industry, SNYDER is a women-owned agency dedicated to supporting a diverse group of artists.

“I’m really proud of what we’ve built,” Irannejad says. “Representation really matters to us.”

Part of SNYDER’s mission involves doing pro bono work. They have paired artists with campaigns for organizations including When We All Vote, Water.org, WaterAid, the Human Rights Campaign, and The Trevor Project.

“We’re very vocal about our politics, and I think that historically has been frowned upon for companies. From our inception, it’s worked in our favor because we just are who we are, and we welcome our artists to be who they are.”

Love what you do.

Irannejad calls herself a late bloomer because it took her many years to find her passion.

“I love a Monday morning. I genuinely love what I do, and I think the artists I work with see that, and the clients do too,” she says. “When people want to buy a product because it has beautiful artwork and packaging created by one of my artists, or if they notice a TV commercial, social media campaign, or mural, and it makes them pause for a second—it brings something that is a reprieve, a visual piece of joy—I think people underestimate the power that has.”

Libby VanderPloeg, one of Irannejad's clients, created the animation Lift Each Other Up, which went viral shortly after the 2016 election.

Revitalizing Music Education in Schools

Michael Reynolds’ Classics for Kids Foundation supports string programs across the US

By Mara Sassoon | Photo Courtesy of Michael Reynolds

$8 billion. That’s the National Science Foundation’s yearly budget. Meanwhile, federal funding for the National Endowment for the Arts, which has suffered major budget reductions over the years and which the Trump administration has repeatedly called for eliminating, is around $160 million per year. And the disparity trickles down to the steady decline in funding for school arts programs, including music education.

Michael Reynolds, a cellist and longtime CFA professor of music, created the Classics for Kids Foundation to support youth strings programs.

“The budget cuts are devastating,” says Michael Reynolds, a cellist and longtime CFA professor of music. String programs, he says, are often the first to be cut because the instruments are typically more expensive and more fragile than wind and brass instruments. And often, trumpets, tubas, and trombones get priority if a school has a marching band.

Reynolds is working to change that. In 1997, he established the Classics for Kids Foundation (CFKF), a grant program that supports string programs serving rural and at-risk youth in all 50 states. The foundation’s matching grants fund high-quality string instruments, including ukuleles, guitars, and harps. At first, CFKF supported only public school programs, but the organization has grown over the years to back all types of youth music initiatives, such as those by Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

“Now, almost half of the programs we support are brand-new programs and initiatives that are springing up all over the country—it’s very exciting,” says Reynolds, who has played with the renowned Muir String Quartet since it was founded in 1979 and also works with Boston University Tanglewood Institute’s String Quartet Workshop. “I think there is a lot of developing knowledge that this sort of thing really helps kids to thrive—academically, socially, and behaviorally.”

The son of two violinists, Reynolds was always surrounded by music. His father founded Montana’s Bozeman Symphony and his mother started the now-thriving orchestra program in Bozeman’s public schools. Before his parents settled in Montana, “music life in Bozeman was pretty quiet. My parents gradually became the epicenter of that music life there,” says Reynolds. He joined the program his mother started and thought back to his own formative school orchestra experience when founding CFKF.

The foundation provides grants to 60 to 70 organizations each year, and Reynolds is in the process of setting up an endowment with the hopes of reaching even more. This year’s recipients had to contend with shifting their programming online due to the pandemic, says Reynolds, but “they all went virtual and were amazingly vibrant and active. Nobody shut down.”

What is most fulfilling for Reynolds is hearing from the students that CFKF grants have benefited.

“I heard from a student living in a community with gun violence who said playing the violin makes them feel safe. Giving that kind of positive experience to a kid can be truly transforming,” he says. “We are seeing how playing an instrument helps give kids a sense of meaning and joy in sometimes very tough personal, family, and community circumstances. That’s exactly what I was hoping would happen from the beginning. I’m very proud of what we are doing.”

Learn more about the Classics for Kids Foundation at classicsforkids.org.

A Note from Harvey: Fall 2020

Calls for Justice

Photo by Natasha Moustache

I have been thinking about Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black boy who was murdered in 1955 by two white men in Money, Miss. If he were alive today, Emmett would be fast approaching his 80th birthday. He would be a few years older than Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Even at an advanced age, Emmett would have swagger.

When his mother made the bold decision to allow the world to see his bloated dead body, she sought to render visible the violence that often targets African Americans. If people could see the effects of bias, prejudice, and racist hate on the most innocent among us—a child—then a campaign for justice to safeguard future generations might occur.

Rosa Parks remembered Emmett Till when she chose not to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Ala. Muhammad Ali, who was almost the same age as Emmett, found lifelong inspiration to fight for equality and justice. Countless others were awakened to action.

Today, the spectacle of dead or injured African Americans is distressingly common. Videos are pushed to our handheld devices: Eric Garner and George Floyd gasping for air; Walter Scott and Jacob Blake getting shot in the back. A social media campaign, #SayHerName, has helped spotlight the similarly horrific experiences of Black women, including Breonna Taylor and Michelle Cusseaux.

It is a sobering fact that our newest undergraduate students were nine years old when Trayvon Martin was killed. They were the same age as Tamir Rice, who was twelve years old when he was shot to death on a playground in 2014. Much of their tween and teenage years have been spent witnessing death.

Our current students are rejecting the inheritance of systemic racism. They have taken to the streets to call for justice. They have organized within CFA to make very reasonable demands, including antiracist training, more staff and faculty of color, and more inclusive syllabi.

I am proud of CFA students and alumni who have chosen to stand up and speak out as part of efforts to end racism everywhere and create actively inclusive communities. I am impressed by CFA staff and faculty who, in the midst of a global pandemic, have organized workshops, overhauled syllabi, and begun to revise conceptions of core and canon across disciplines.

There is more work ahead. If you would like to support efforts toward active inclusion or share your thoughts on why it matters, please email me at cfadean@bu.edu.

Harvey Young, Dean of CFA

A New Look at Set Design

By Joel Brown | Photos courtesy of Afsoon Pajoufar

COVID-19 shut down most live theater at least through 2020, but when plays come back, Afsoon Pajoufar (’19) will be building worlds again. A New York–based set designer for plays, operas, and film, she’s designed for New Repertory Theatre, Gloucester Stage, Brooklyn Academy of Music, and many others. Trained as a painter in her native Iran, Pajoufar studied scene design at CFA, where her work on a 2017 production of Cabaret was chosen for the 2019 American Exhibit at the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space.

Afsoon Pajoufar ('19), a New York–based set designer for plays, operas, and film.

You didn’t start out as a designer.

The overall culture in Iran is parents want their children to be doctors or other “successful” careers. I was “the bad child.” I went the opposite direction—I wanted to go to art school.

You were a painter. What happened?

As a sophomore in college, I got this feeling that I had to go beyond the two-dimensional space of the canvas. I have a fascination with the relationship between the human body and space.

What’s your set design method?

Research is the first phase. But for me, the next step is model making. I find it much easier when I think with my hands.

What’s the most unusual material you’ve used?

In s.i.n.s.o.f.u.s. (at Harvard in 2018), I replaced the main rag—the house curtain—with orange construction netting.

What skills do you use most?

I’ve found it really satisfying to explore a wide array of disciplines—photography, printmaking, sculpture, graphic design. I bounce around the room during rehearsals, between the actors, taking photos. I can evaluate the design in my head when I share the space with the actors.

"I bounce around the room during rehearsals, between the actors, taking photos. I can evaluate the design in my head when I share the space with the actors."

You often say you design environments rather than sets.

It’s not only about the actors, it’s about the relationship between the actors and the audience. In the production of Cabaret, I considered the whole space, designed the audience space as well.

What’s a mistake you’ve learned from?

They say take all opportunities that come to you after graduation. That is the worst suggestion. I learned I don’t need to say yes to everything. Sometimes you can read the signs that this won’t be the right production, that I won’t be the right collaborator for it.

How has COVID-19 affected your work?

Four or five productions I had lined up for April, May, and June were canceled or postponed. It’s had a negative effect on so many people’s careers in theater, but especially for the new people.

But you sound upbeat.

I’m in touch with my collaborators. We talk about the shape of theater after the pandemic. We are finding ways to keep making things. Maybe we have to use digital platforms that will challenge the idea of theater: is it theater or not? We keep pushing.

Tell us your dream for when we come back.

I want to explore more operas. The music brings an abstract quality into my design. And operas receive big budgets, so of course I’d love to explore unlimited options as part of my design.

Class Notes: Fall 2020

Class Notes

1960s

Emory Fanning (’64), an organist, performed a solo recital on March 8, 2020, at Middlebury College’s Mead Memorial Chapel. The performance featured works by Louis Couperin, César Franck, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

1970s

Kate Katcher (’73) was one of 10 writers to participate in theater company Thrown Stone’s Acts of Fate, which premiered on Zoom in June 2020. The show was a collection of memoir, performance, and poetry that answered the prompt: “What was the moment in your life that changed everything?”

Peri Schwartz (’73) showcased her recent body of work, “Studio Interiors,” which features dynamic, flattened compositions that focus on the interplay of color, light, and space at Gallery NAGA in Boston in January 2020.

Carol Barsha (’75,’77) had her closely observed nature studies and flowery landscapes featured in the exhibition Landscape in an Eroded Field at the American University Museum in Washington, D.C., from January to March 2020.

Paula Plum (’75) received the 2020 Elliot Norton Award in the Outstanding Actress, Midsize Theater category for her performance in The Children with SpeakEasy Stage Company.

Sue O’Daniel (’78) retired from her 42-year career as a music teacher at Vergennes Union High School (VUHS) in Vergennes, Vt., in June 2020. During her time at VUHS, she grew the music program, school musicals drew ticket requests from across the state of Vermont, and band participants grew to 25 percent of the student body.

Paul Schulenburg (’79), a painter, is represented by Addison Art Gallery in Orleans, Mass. The gallery recently published a book of his work, Paul Schulenburg: Oil Paintings (Addison Art, Inc., 2020), which features landscape and figurative oil paintings from the past 20 years.

1980s

Todd London (‘80,’81) is an essayist, novelist, arts journalist, and theater historian. He presented his workshop “Let Me Sit With You a While, or the Challenge of Theater is the Challenge of the World” in February 2020 as part of the School of Performing Arts at Virginia Tech’s colloquium series “Art, Community, Ecology, and Health.” The series focused on the “power and practice of art and culture as essential elements of healthy communities.”

Julia Shepley (’80) was a resident at the Scuola Internazionale di Grafica in Venice, Italy, and exhibited her sculpture work in RING, the Boston Sculptors Gallery annual members’ group exhibition, from January 29 to February 23, 2020, and in The Gold Standard of Textile and Fiber Art at Westbeth Gallery in New York City in February 2020.

Jason Alexander (’81, Hon.’95) starred in Closing the Distance, a scripted podcast exploring social distancing, quarantine, and isolation in a series of 10 short audio dramas. Alexander also participated in Stephen Sondheim’s 90th birthday celebration concert on Broadway.com along with Brad Oscar (’86) and Greg Hildreth (’05).

Karen Carpenter (’81) directed a reading of Bette Davis Ain’t for Sissies, a one-woman show that tells the story of Bette Davis’ fight against the male-dominated studio system, in February 2020. The play has had multiple runs at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in the United Kingdom and had a US tour in 2015.

Julianne Moore (’83) is starring as Gloria Steinem in the film The Glorias. The film is based on Steinem’s memoir, My Life on the Road. In January, Moore moderated a roundtable discussion in New York City during which gun violence survivors shared their personal stories. The event was sponsored by People magazine and the nonprofit advocacy organization Everytown for Gun Safety. Moore also signed an open letter by Guns Down America urging studios to end contributions to candidates who take money from the NRA and vote against gun reform.

K. Johnson Bowles (’86) had 46 works from her most recent body of work, Veronica’s Cloths, selected for publication in 24 art and literary journals, including the American Journal of Poetry, Twyckenham Notes, and The William and Mary Review. She showed Veronica’s Cloths in an online solo exhibition with PH Gallery of Troy, N.Y., through July 2020.

Brad Oscar (’86) played Frank Hillard in Broadway previews of the musical comedy Mrs. Doubtfire.

Suzanne Teng (’86), a flutist, received the Album of the Year award from the Native American Style Flute Awards and a gold medal from the Global Music Awards, both in April 2020, for her newest album with musical partner Gilbert Levy, Autumn Monsoon.

Nanette Kaplan Solomon (’87) is a pianist who performed in “From the Salon to the Shtetl: A Selection of Works for Clarinet, Violin and Piano” at the Hoyt Art Center in New Castle, Pa., on March 12, 2020. Solomon is also a professor emerita of music at Slippery Rock University.

Suzanne Wilson (BUTI’88) became the president and CEO of the Phoenix Symphony in January 2020. Wilson was previously the executive director of the Midori Foundation, which provides high-quality, sequential music education programs to students in over 70 New York City public schools and organizations that have little to no access to the arts.

The Philadelphia Orchestra commissioned a new work, “Seven O’Clock Shout,” from Grammy-nominated composer, flutist, and teacher Valerie Coleman (BUTI’89, CFA’95). The piece, which honors frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, debuted at the Philadelphia Orchestra’s online HearTOGETHER event in June 2020 (pictured here), which featured performances by individual members of the orchestra, as well as stars such as Wynton Marsalis (Hon.’92). Coleman was also the featured keynote speaker for the closing of the League of American Orchestras online conference in June 2020. Video courtesy of the Philadelphia Orchestra

Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94) is an opera producer whose company, Beth Morrison Projects, offered an “Opera of the Week” during the pandemic. Each opera was posted on bethmorrisonprojects.org.

1990s

In a special video for graduating student artists, CFA alums sent their well-wishes and advice to the Class of 2020. Actor Kim Raver (’91), top right, told grads, “Stay curious. Stay disciplined. Stay connected to your friends. Stay creative. And stay true to yourself.” Other alums featured in the video were, clockwise from top left, painter Sedrick Huckaby (BUTI’95, CFA’97), opera singer Sandra Piques Eddy (’99,’02), film producer John Bartnicki (BUTI’02, CFA’07), oboist Eugene Izotov (’95), and actors Uzo Aduba (’05), Julianne Moore (’83), and Michael Chiklis (’85).

Rebecca A. Hartka (BUTI’92, CFA’02,’07), a cellist, has performed with Grammy-nominated guitarist José Lezcano as Duo Mundo. They performed together this past winter in New York and Mexico until COVID-19 shutdowns.

Abraham Higginbotham (’92) was a writer and producer for the Emmy Award–winning series Modern Family, which concluded in spring 2020 after 11 seasons.

Nancy King (’93) directed a production of selections from Purcell’s epic tragedy Dido and Aeneas, performed by UNC-WOOP! in March 2020 for the 18th annual Opera Sunday event in Southport, N.C. King created UNC-WOOP!, an opera outreach project at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, as a means to provide her students with opportunities to hone their live performance skills and introduce the public to opera in a relaxed, lighthearted manner.

Michael Medico (’94) directed the January 30, 2020, episode of Grey’s Anatomy, “A Hard Pill to Swallow,” which also featured Kim Raver (’91) as the character Dr. Teddy Altman. He also directed a table read of the pilot episode of the show The Fosters over Zoom, which reunited many of the show’s cast members. The Fosters co-creator and executive producer Peter Paige (’91) read the stage directions for the virtual event, which benefited The Actors Fund.

Brian Reagan (‘94) was appointed superintendent of schools for Waltham, Mass., in March 2020. Reagan was previously the Wilmington, Mass., assistant superintendent.

Amanda Gentry (’95) opened her contemporary ceramic exhibit Murmuration at the Cuesta College Harold J. Miossi Art Gallery in spring 2020 in San Luis Obispo, Calif. The interactive exhibit explored the individuality of one’s voice in isolation.

Russell Hornsby (’96), center, in long-sleeve red shirt, starred in the NBC show Lincoln Rhyme: Hunt for the Bone Collector, about a forensic criminologist whose search for a serial killer left him paralyzed. In February 2020, he returned to BU to visit a senior theater class (pictured here). He also participated in From a Distance: BUTV10 Variety Hour, a virtual showcase featuring exclusive interviews and words of wisdom for BU students, and joined fellow actors Kim Raver (’91) and Jessica Rothe (’09) to surprise graduating seniors during the first virtual BU Senior Breakfast.

Susanna Klein (’96) has self-published Practizma Practice Journal: 16 Weeks of Efficiency, Empowerment & Joy for Musicians, which includes strategies for musicians to get more out of their practice sessions. She blogs and presents nationally on musician health and empowered and joyful practice in music.

Hannah Barrett (’98) was appointed the director of the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. Prior to this appointment, Barrett, an award-winning artist and educator who has taught, lectured, and exhibited widely, was the international program coordinator at Bard College Berlin, Germany.

Angela Fraleigh (’98) presented an exhibition of her work, Sound the Deep Waters, at the Delaware Art Museum in fall 2019. The exhibition presented a contemporary look at gender and identity through the lens of historic narrative art.

2000s

Gregg Mozgala (’00) starred in Caryl Churchill’s Light Shining in Buckinghamshire at the New York Theatre Workshop and in the play Teenage Dick, both in 2018. Mozgala is an activist for the disabled community in the arts.

James Perrin (’01) had an exhibition of his paintings, Percept Upon Percept, at Hope College in Michigan in February and March 2020. Perrin’s paintings “explore the integration and resolution of disharmonious elements relating to themes in painting and its processes: abstraction and representation, surface and illusion, discord and resolution, chaos and structure.”

Duncan Cumming (’03), a pianist, performed at the First Presbyterian Church of Ironton in Ironton, Ohio, in January 2020. He performed as one half of the Capital Duo, which also features his wife, violinist Hilary Walther Cumming.

Uzo Aduba (’05) will appear in Americanah, a 10-episode miniseries set to air on HBO Max. The series is based on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 novel of the same name, which tells the story of a young Nigerian woman who immigrates to the United States.

Sara Chase (’05) played Cyndee Pokorny in the Netflix interactive movie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt: Kimmy vs. the Reverend, a role she also played in the series.

Greg Hildreth (’05) was set to play Peter in the Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s musical comedy Company at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theater before Broadway performances were suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jennifer Bill (’07), Emily Cox (BUTI’08, CFA’13,’15), Zach Schwartz (’13, CAS’13), and Amy McGlothlin (’15), members of the Boston-based saxophone group Pharos Quartet, performed with composer and pianist Thomas Weaver (’13) in January 2020 at BU’s Marsh Chapel.

Steve Eulberg (’07) plays the dulcimer and frequently collaborates with mountain dulcimer player Erin Mae Lewis. The two have shared their music through radio broadcasts, master classes, and performances.

Beth Willer (’08,’14) joined the faculty of the Peabody Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., as associate professor and director of choral studies. Willer is also the founder of Lorelei Ensemble, a women’s vocal ensemble.

Jason Berger (BUTI’09, CFA’14) became known as “Delaware’s opera singing barista” after a customer filmed him serenading her husband while serving him coffee at a Starbucks in Wilmington. Berger is studying at OperaDelaware’s Young Artist Program.

Clare Longendyke (’09), a pianist, and Rose Wollman, a violist, performed in a concert in February 2020 at Saint Meinrad Seminary and School of Theology in St. Meinrad, Ind. The concert drew from their album Homage to Nadia Boulanger (2019) and consisted of four pieces by the late French composer Boulanger and her composition students.

Alex Wyse (‘09) is the co-creator and cowriter, with Wesley Taylor, of Indoor Boys, an LGBTQ+ digital comedy series that “follows two homebody roommates as they navigate the boundaries of their no-boundaries friendship.” Wyse, who also stars in the show with Taylor, won a 2020 Indie Series Award for Best Actor. He and Taylor together received awards for Best Comedy Series, Best Directing-Comedy.

2010s

Richard Andrew Schwartz (’10) is an associate professor of music at Eastern New Mexico University in Portales, N.M. The saxophonist released his album Song for My Mother, which features two original compositions, “Alpha Cat” and “7-11 Blues,” recorded with the late jazz legend Ellis Marsalis.

Samantha Silverman (’11) illustrated a Curbed New York story on how New Yorkers are using their apartment building stoops as spaces for connection and community during the pandemic.

Jimmy Greene (’12) released Flowers: Beautiful Life - Volume 2, a companion to his 2014 album Beautiful Life. Both albums remember the saxophonist’s daughter, Ana, who was murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. Greene also performed with the Jimmy Greene Quintet at Columbia University School of the Arts as part of its 2019–2020 jazz series in February 2020.

Francesca Blanchard (’14), a folk singer-songwriter, released a new song, “Ex-Girlfriend,” in February 2020.

Throughout summer 2020, BU Tanglewood Institute (BUTI) hosted Intermissions: A Spotlight Conversation Series. The eight-week series consisted of live-streamed conversations with BUTI alumni and friends, including conductor Teddy Abrams (BUTI’03), bassist Joseph Conyers (BUTI’98), harpist Angelica Hairston (BUTI’08,’09), clarinetist Anthony McGill (BUTI’95), producer Beth Morrison (BUTI’89, CFA’94), composer Nico Muhly (BUTI’96,’97), flutist Olivia Staton (BUTI’12,’13,'14), and soprano Sarah Vautour (BUTI’11). Topics ranged from music performance and education to the many facets of building a career in classical music.

Maya French (’15) is a cofounder, coartistic director, and comanaging director of Palaver Strings, a string ensemble and nonprofit organization based in Portland, Maine. The violinist is also a faculty member at Bay Chamber Concerts Music School and the education director for Chamber Music Now, an annual weeklong festival in Portland, Ore.

Ellen Humphreys (’15) plays Sharon Russell in the CBS All Access drama Interrogation. She also makes an appearance as a bank teller in the forthcoming film Silk Road.

Courtney Miller (’15) is an assistant professor of oboe at University of Iowa in Iowa City, Iowa. She released her second album, Portuguese Perspectives (MSR Classics, 2019), which features world-premiere recordings for the oboe by Portuguese composers.

Rebecca Ness (’15) exhibited her paintings in a show that ran from December 2019 through January 2020 at the Alexander Berggruen Gallery in New York City. Her body of work featured in the exhibition explores both portraiture and the objects of domestic and artist-studio life.

Laura Randall (’15), a flutist, and Jessica Cooper (’17,’19), a violist, participated in Newton Covenant Church’s hour-long live “Concert for Chromebooks” on Zoom on April 9, 2020. The Newton, Mass., church’s benefit concert raised money to provide 20,000 Chromebooks for Boston Public School students without access to a computer at home. The concert also supported professional musicians whose scheduled engagements during Holy Week and beyond were canceled due to the pandemic.

Aija Reke (’15) performed “Memoire de Claire,” a piece inspired by the French composer Olivier Messiaen, on the violin as part of the Charm of Impossibilities concert at BU in February 2020. The piece was written by Elena Levi (’21).

Alexander Golob (’16) painted a mural memorializing George Floyd in Jamaica Plain, Mass., in June 2020, outside a marijuana dispensary, which funded the project. In late July, it was moved for display inside the dispensary. Proceeds from the mural were donated to Boston Art & Music Soul (BAMS) Fest, a nonprofit that works to “break down racial and social barriers to arts, music, and culture.” Courtesy of Alexander Golob

Natalie Guerrero (’16) launched a Venmo campaign to support the National Bail Fund and the George Floyd Memorial Fund. She raised more than $67,000.

Christian Frentzko (’17) and his wife, Jennifer Sisco, are public school teachers in New Jersey and perform as the musical duo The Harrisons. Throughout the pandemic, they have been streaming their performances on Facebook.

Matthew Scinto (’17) is the music director of the Cape Cod Chamber Orchestra (CCCO). He conducted the CCCO in its second annual An Afternoon of Chamber Music winter concert in February 2020.

Annalise Cain (’18) played The Bastard character in Shakespeare’s King John at the Calderwood Pavilion at Boston Center for the Arts from January 30 to February 16, 2020.

Lina González-Granados (’18) was awarded a Sphinx Medal of Excellence, which recognizes extraordinary classical Black and Latinx musicians. González-Granados is an internationally celebrated conductor and the founder and artistic director of Unitas Ensemble, a chamber orchestra that performs the works of Latinx composers and provides access to free performances for underserved communities.

Scott Humphries (’18) was named the Indiana Music Education Association’s 2020 Outstanding Collegiate Educator. He was nominated by a student at Manchester University in North Manchester, Ind., where he is assistant professor of music and director of instrumental studies and music education.

Krishan Oberoi (’18) is the new artistic director of the Falmouth Chorale in Falmouth, Mass. Oberoi is also the founder and principal guest conductor of SACRA/PROFANA, a San Diego–based chorus, and in 2018 he founded the Boston-based Analog Chorale. Oberoi has engaged diverse populations through innovative education and outreach programs, including an after-school program for students impacted by homelessness.

Leyla Tonak (’18) had her first solo show, New Mythologies, at Ghost Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y., in January 2020. Tonak makes large-scale oil paintings that explore gesture and metaphor through the lenses of sex, power, and family.

Zimeng Wang’s A Banned Exhibition was recognized with a 2020 Graphic Design USA Award. Courtesy of Zimeng Wang

Keith Heimann (’19) has been named executive director of the Association Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale (RIdIM), an international index of visual sources of music, dance, theater, and opera.

Colleen Kinslow (’19) launched Cadmium, an independent online magazine, in May 2020. Kinslow created the magazine “in the hopes of memorializing and honoring those who matter most: our communities, friends, peers, colleagues, family, and ourselves.” You can read the magazine at cadmiummag.com.

Zimeng Wang (’19) received a 2020 American Inhouse Design Award from Graphic Design USA for work she created for her 2019 thesis project, A Banned Exhibition. The project focused on Chinese government censorship. Wang sourced thousands of words banned by Chinese media and presented various forms of banned information in a subversive and humorous way.

Objects of Her Affection

Anna Valdez layers personal stories into lush, plant-filled paintings

By Andrew Thurston | Photos by Shaun Roberts

Artist Anna Valdez’s California studio is full of plants. Vines tumble from shelves stacked with art books, and succulent green leaves frame oversized canvases. Her childhood home bloomed with flora, too: her dad grew up on a farm and worked in a nursery.

Self-Portrait in Studio (2019) Oil and acrylic on canvas 72 x 72 in. In this piece, Valdez has obscured her face behind a fiddle-leaf fig plant.

“Plants remind me of home and they just bring life to a space,” says Valdez (’13). “And they provide form in my paintings. They grow into the space and create lines. They really help me in navigating my compositions.”

Plants are everywhere in Valdez’s recent creations: in 2019’s Self-Portrait in Studio, the artist’s face is hidden by fiddle-leaf figs; 2018’s Landscape in Studio is a painting of a painting of palms, snake plants, and more.

Valdez’s work—primarily oil on canvas, but also monotypes, ceramics, and wallpaper—has been shown at galleries and museums across the United States and Canada. In 2018, Facebook commissioned her to paint a mural in one of its Menlo Park, Calif., buildings.

In its review of her 2019 New York exhibition Natural Curiosity, art and culture magazine Juxtapoz complimented Valdez’s “signature palette of rich reds, bright yellows and sumptuous surfaces,” calling the show “visual poetry at work, at once rooted in art-historical practices while also remaining faithful to the present moment.” Vice has said her “houseplant paintings have seriously chill vibes.”

These items in Valdez's studio make appearances in paintings such as Objects of Affection (below, right).

Valdez has painted sparse deserts, rocky bays, even old beer cans, but for the past couple of years, her botanical studio has been the star of her work. It’s not just crowded with plants. The space is filled with canvases and painting supplies, books, fabric wall hangings (her mom is a quilter), sculptures, pottery, shells, an upturned milk crate.

“The paintings I’m making right now are very much about the studio,” she says. “It’s an environment that I have complete control over and have curated over time. I suppose I end up loving the space that I am creating as it becomes reflective of a personal landscape or as a self-portrait.”

In 2020’s Objects of Affection, the canvas brims with details from Valdez’s studio. A skull, a Venus de Milo statue, and an amphora of the goddess Diana fight for space on the desk; a cow pelvis leans against a stack of books about women artists. There’s a story in the objects—all what she calls symbols in art history.

“I wanted to make a painting that glorified women in art, but without it being a nude of a woman reclining,” she says. “When you see women depicted in art, it’s usually from a male lens, so it’s usually sexualized.”

Objects of Affection (2020) Oil on canvas, 85 x 80 in. The painting brims with details from Valdez's studio.

Objects of Affection is a big painting, more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Valdez says she spent a lot of time climbing up and down a ladder to add the many details.

“It’s a very physical action to make that painting,” she says. “It’s interesting because big paintings are considered masculine paintings. I like that little bit of duality in the piece.”

Valdez appears in few of her paintings, but says they’re all “self-portraits to some degree.” Before becoming an artist, she studied anthropology and archaeology and sees parallels between recording the past and chronicling her present.

Objects of Affection, solo exhibition installation at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Fancisco, Calif.

“When I was studying archaeology, we would re-create and reconstruct someone’s life based off the objects that were in that space,” she says. “You would write a story from the things they surrounded themselves with.”

Despite her autobiographical approach to art, Valdez’s paintings are not straightforward retellings of her life. The paintings show not only what she sees in the studio, but what’s on her mind—things she’s noticed and thought about over days and weeks.

“There are so many moments that go into making one painting,” she says. “I try to layer a lot of moments into a piece. You see me as a person in it.”

Boston View with Taxidermy Butterflies (2019) Oil and acrylic on canvas 52 x 42 in. In some of Valdez's paintings, the view shown from a window may be an artistic lie: a snapshot from a previous day or even of a different place altogether.

Occasionally, the view shown from a window may be an artistic lie: a snapshot from a previous day or even of a different place altogether. Sometimes, the artworks shown hanging on her studio walls live only in Valdez’s sketchbook—they have no canvas of their own.

“And there are little surprises that happen,” says Valdez. If she paints a vase into a picture that doesn’t exist beyond the canvas, she’ll try to re-create the vase in real life—then paint it, for real this time, into another work. “I like to play,” she says. “I like to not take myself too seriously.” When galleries show her work, viewers can track the genesis of an object: the painting that gave birth to its fictional creation, the ceramic that made it real, the painting that immortalized it.

“I am fascinated by how one idea can lead into the next,” says Valdez. “Or, more specifically, how one painting creates an idea for the next painting. Incorporating ceramics and other mediums into my still life installations feels like a natural step.”

Landscape in Studio (2018) Oil and acrylic on canvas 66 x 84 in. Most of Valdez’s paintings start with a rough ballpoint pen sketch. Then she'll do an underpainting in acrylic before building the final piece with oil paints.

Most of Valdez’s paintings start with a rough ballpoint pen sketch—she carries a sketchbook everywhere. Once she’s set up her canvas, she’ll do an underpainting in acrylic—“just getting the skeleton of the painting down”—then begins building the final piece with oil paints. The paints are homemade: she buys pigments, mixing them with oils in her studio. It’s a practice she picked up during Associate Professor Richard Raiselis’ CFA classes on painting and color.

“It’s this journey of this relationship to making the whole painting,” says Valdez, who compares it to growing, making, and fermenting her own food. “It gives me a better understanding of why certain colors will work with each other, understanding the chemistry of why one pigment is oilier than another, its absorption rate, its lightfastness, how it will change over time.”

Anna Valdez (’13) has filled her California studio with plants. “Plants remind me of home and they just bring life to a space,” she says.

Reviewers often comment on Valdez’s use of color, praising its Californian brightness or making favorable comparisons to Henri Matisse. But her relationship to the vibrant colors in her work is complicated. It’s one reason she doesn’t expect the COVID-19 pandemic to reshape what or how she paints.

“I’ve struggled with depression and anxiety for most of my adult life,” she says. “People will look at my paintings and they’ll assume I’m a really happy person. These things are ways of focusing my energy and being able to step into this reality that I’m creating. I don’t want to change that, because I find safety in these spaces I’m creating.”

The Future of Opera

Chicago Opera Theater Music Director Lidiya Yankovskaya is one of America’s few women conductors and a force for change

By Andrew Thurston | Photo by Karen Almond

If you watch any US orchestra, particularly one with a multimillion-dollar budget, you’re almost guaranteed to see a white man standing on the conductor’s podium. Most estimates put the share of women conductors in America at or below 10 percent—and that’s only if you include those holding the baton for community groups, youth orchestras, and summer festivals.

At Chicago Opera Theater, Lidiya Yankovskaya is among the few to crack an especially thick glass ceiling. She’s one of only a handful of women conducting at a leading US orchestra—and one of just two at a major opera company.

“There’s a larger percentage of women who are studying conducting at universities, conducting with smaller organizations, or doing really fantastic work out there,” says Yankovskaya (’10), who sets the tempo and cues in the musicians as Chicago Opera Theater’s Orli & Bill Staley Music Director. “Not enough of them have gotten opportunities to move to the next level and work with larger-budget institutions. But I think it’s changing and will probably continue to change.”

In part, that change is a result of Yankovskaya’s efforts. She chooses work that lifts young composers and helps mentor women looking to follow in her path.

"Her presence behind the podium is breaking down barriers that have long existed for women in the industry.”

“Her presence behind the podium is breaking down barriers that have long existed for women in the industry,” says Ishan Johnson, associate director of development at Chicago Opera Theater. A voice performance major at CFA, Johnson (’06) has known Yankovskaya since 2008, when the two worked on an Opera Boston performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose. “There is a lack of minority and women leadership in opera administration, and Lidiya seeks to change that.”

A Nontraditional Trajectory

Born in perestroika-era St. Petersburg, Yankovskaya spent her early childhood in a crumbling Soviet Union, then in a Russia struggling to find its identity. As the country staggered through coups and constitutional crises, waves of Jewish families left, including Yankovskaya’s. In 1995, they fled their home in Russia and became refugees.

“I remember passing by a major square in the middle of the city where fascists would fly large swastika flags and hand out pamphlets that said ‘Kill all the Jews’ on them,” she told Newsweek in 2016. “Russia, in general, at the time was in economic and political turmoil, so there was a lot of hardship overall. When that happens, people tend to blame any larger minorities that exist.”

Many Russian Jews emigrated to Israel, but the Yankovskayas came to upstate New York. Despite the upheaval for young Lidiya—just nine when her family moved across the world—there remained one constant: music.

As a child, Yankovskaya studied piano and voice, adding violin when she moved to the United States. Music was more than a hobby. “It was always something I lived for and that was a top priority for me. I even remember as a kid saying I’d rather just stay home and practice than go do the social thing.”

During high school and college—she studied music and philosophy at Vassar College—Yankovskaya kept practicing and playing, but wasn’t sure what a life in music would look like.

“You see these traditional musical trajectories of where your career would be,” she says. “For me, it seemed that solo piano would be the thing I would have to do, and I did not want to sit alone in a practice room for that many hours and be traveling alone. That just wasn’t right for me.”

Her undergraduate experience included conducting—and she’d even had a few turns with the baton as a teenager. But it was “not something I realized you could make a career out of,” says Yankovskaya.

At CFA, her thinking began to change. For two years, Yankovskaya studied musicology, music theory, and conducting techniques, learning the technical skills necessary to hold an orchestra together. She also began to work as a conductor, standing out front for Opera Boston, Boston Opera Collaborative, and Lowell House Opera. After graduation, she was appointed artistic director and conductor for the Juventas New Music Ensemble, a group dedicated to performing the work of young, contemporary composers, and later added the Commonwealth Lyric Theater to her résumé. Soon, she was being hailed as a rising star.

“If there were a futures market for classical music, the touts would be pushing Lidiya Yankovskaya,” wrote Keith Powers for WBUR in March 2017. “She’s busy. She’s busy because she’s good.”

Three months after that glowing review, Yankovskaya was named music director at Chicago Opera Theater.

“She is as skilled with operas of the past as she is with works of living composers,” said the president of Chicago Opera Theater’s board of directors, Susan J. Irion, of the appointment. “Lidiya is sure to be a charismatic ambassador of opera in today’s world.”

New Audiences

There’s a common conductor stereotype: tyrannical, wild-eyed, eccentric. It’s generally unfair—and it’s definitely not Yankovskaya. She describes conducting as a collaborative process, working with individual musicians to help them become part of a whole. Sometimes, that simply requires her to provide a channel for them to connect with each other; other times, she has to firmly guide them. She says each group of musicians and each piece of music bring their own dynamic—it’s as much an exercise in psychology as understanding and interpreting a score.

“One type of artistic work may require something very rigid and precise, while another needs complete freedom,” she says. “One of the things I strive for is figuring out for each piece of art, what does this piece need from me in this moment, what do I need to do to create the greatest impact?”

There’s also plenty that happens offstage and outside of rehearsals. Yankovskaya is a leader and figurehead for Chicago Opera Theater, working with donors and shaping the organization’s direction through its choice of shows. Given her history, Yankovskaya is especially interested in Russian masterpieces, but she’s also an advocate for contemporary opera. Under her leadership, the theater has given Chicago premieres to work as diverse as Jake Heggie’s 2010 opera, Moby-Dick, and Tchaikovsky’s 1892 lyric opera, Iolanta.

As music director of the Chicago Opera Theater, Lidiya Yankovskaya ('10) makes it a point to choose work that lifts young composers and helps mentor women looking to follow in her path. Photo by Kate Lemmon

"One of the things we focus on is bringing work to the stage that speaks to our audiences today and that is about issues or questions that may arise for our audience."

“One of the things we focus on is bringing work to the stage that speaks to our audiences today and that is about issues or questions that may arise for our audience,” says Yankovskaya. “Even if it’s for traditional work, making sure that we connect it to our audiences and their experience.”

One part of that is helping the theater reach new audiences. In February 2020, the theater premiered Dan Shore’s Freedom Ride, about the civil rights activists who rode buses to protest segregation. The show was produced in partnership with the Chicago Sinfonietta, which aims to improve diversity in—and increase access to—classical music.

“She’s made a commitment helping to make opera accessible to different communities,” says Johnson, “exploring repertoire that adds to the canon, and finding innovative ways to bring opera to a greater audience.”

Yankovskaya also started Chicago Opera Theater’s Vanguard Initiative, a mentorship and development residency program for emerging opera composers. And, as music director, she’s involved in the theater’s broader educational efforts, including one in Chicago Public Schools that gives children the chance to write their own operas.

Just before she spoke with CFA, Yankovskaya was on a call in support of the Taki Concordia Conducting Fellowship, which mentors young women hoping to make it at the highest level. In 2015, she was one of those who benefited from its backing.

“One of the most important things in order for any industry—for our world—to have progress and change moving forward is to attract the brightest young talents,” says Yankovskaya. “It’s also important to make sure that we fight the inequities that exist that prevent new ideas from entering our work.”

A Refugee Orchestra

As a refugee, Yankovskaya is also focused on tackling the inequities that impact people forced to flee their home countries.

In 2016, she founded the Refugee Orchestra Project to help raise awareness of the role émigrés play in American society. The orchestra, which has played concerts across the northeastern United States and in the United Kingdom, brings together musicians who found shelter in the US after escaping persecution, as well as their families and friends. Yankovskaya says the nonprofit proved especially vital during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Because so many refugees lack family networks or other support systems, they’re especially vulnerable to health or economic insecurities.

Yankovskaya founded the Refugee Orchestra Project in 2016 to raise awareness of the role émigrés play in American society. Photo by Scott Bump

“We commissioned composers to write solo work for some of our performers that they can play on their own, record on their own,” she says. “It was an opportunity for the creation of new work and to showcase the artists and composers we work with—and to give them some employment and some opportunity to create.”

With theaters shuttered for much of 2020, Yankovskaya has experimented with other virtual projects, too, including digital performances and online conversations about the inner workings of an opera theater. While that may have encouraged an exploration of different ways of reaching new audiences or sharing music, she says the year has mostly been a chance to reflect on what she loves the most.

“To me, live performance is irreplaceable,” she says. “I so miss being in a room with people making music. I do not think there’s a substitute for that.”

Also in This Issue: How CFA professor Michael Reynolds supports youth music education programs.