Category: Features

Rick Heinrichs’ Magical Worlds

The production designer and CFA alum has overseen the creation of some of cinema’s most iconic places, from Gotham City to Halloween Town to a galaxy far, far away

By Marc Chalufour | Photo by Patrick Strattner

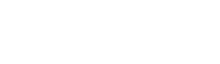

Heinrichs created this model of Jack Skellington, the protagonist of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. © Disney

Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas is a deeply macabre film. The star, a tuxedoed skeleton, has no eyes. His love interest tears her limbs off and sews them back on. A gang of trick-or-treaters kidnaps Santa Claus. A teddy bear gets dissected. Disney, concerned the creepiness wasn’t appropriate for its child-friendly brand, released the film under a different studio banner.

But the late film critic Roger Ebert saw magic. “The movies can create entirely new worlds for us, but that is one of their rarest gifts. More often, directors go for realism,” he wrote in 1993. “One of [Nightmare’s] many pleasures…is that there is not a single recognizable landscape within it. Everything looks strange and haunting.”

Though the film was created by Tim Burton and directed by Henry Selick, visual consultant Rick Heinrichs was critical to creating the immersive world of Nightmare’s Halloween Town. He translated Burton’s sketches into the first sculpture of the film’s protagonist, Jack Skellington, and was a visual consultant throughout production, helping to make Halloween Town a cohesive and believable setting for the stop-motion animated feature. The pair have partnered on 11 feature films—often with Burton directing and Heinrichs (’76) in charge of art direction or production design—including Edward Scissorhands (1990), Batman Returns (1992), and Sleepy Hollow (1999), for which Heinrichs won an Academy Award.

Over the past two years, he has helped filmmakers create J. R. R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth for The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (Heinrichs helped launch the series, then departed) and transform a Grecian island into the set of a murder mystery for Knives Out 2—both scheduled for release this year. Heinrichs’ credits also include work on some of the most memorable worlds in film, including Star Wars (Star Wars: The Last Jedi) and Marvel (Captain America: The First Avenger).

“My fascination has always been the creation of an environment and trying to instill it with expressive quality and emotional content,” Heinrichs says. Few in Hollywood have been as successful. After working his way up through the art departments on both animated and live-action films, Heinrichs has become one of the most sought-after production designers in the business.

Heinrichs first collaborated with Tim Burton on the short film Vincent, about a young boy obsessed with horror actor Vincent Price. © 1982 Disney

HOLDING THE FABRIC TOGETHER

A production designer guides a project’s transformation, from an idea to a three-dimensional world filled with actors, sets, costumes, and lighting. Done well, the result can immerse audiences in a fantasy world. The job requires a photographer’s eye, a sculptor’s hands, and a painter’s sense of color. The more fantastical the world, the greater the challenge in making it believable. “The writers, directors, producers, and actors—it’s pretty easy to figure out who does what,” Heinrichs says. “The rest of a film’s credits are a little bit harder to understand. They’re not directly related to getting butts in the seats. Our contributions are more diffusely woven into the fabric of the film itself.” The production designer must make sure that fabric holds together.

“With Tim, and with all of the other filmmakers I’ve worked with, it’s always been about the director and their vision,” Heinrichs says. “It’s just so powerful, seeing something which coheres around a vision that’s propelled by the storytelling of the director.” And Heinrichs has worked with some of the best, such as Terry Gilliam, Ang Lee, and Joel and Ethan Coen.

ANIMATED DREAMS

An annotated sketch and sculpture Heinrichs created of Nightmare character Sally. © Disney

As a kid, Heinrichs loved films, especially Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons. Art became an escape from the rigid structure of school. “When I was, like, 10, I would draw these imaginary projects with situational themes—like a haunted house where every room had a horrible murder going on in it,” he says. “I think my parents were both amused and concerned.”

Heinrichs wanted to study animation in college, but there weren’t many programs available in the mid-1970s. He opted for a broad background in fine arts. “I spent my late teens and early 20s getting my hands dirty in drawing and painting and sculpture, graphic design, printmaking,” he says. He appreciates how that background continues to benefit his work. “You gain some mastery over depicting the human form in light—that’s a discipline you can apply to many other things.”

By the time Heinrichs graduated, animation programs were beginning to pop up—including one at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where a number of Disney animators taught. “There was this whole group of like-minded individuals there,” he says. He met Brad Bird, John Lasseter, and John Musker (if you’ve watched a Disney or Pixar film in the past 35 years, you’re familiar with their work). He also met Tim Burton.

The two worked together on Disney’s 1981 film The Fox and the Hound, where they were responsible for drawing inbetweens—repetitive frames that create the illusion of motion following an animator’s key frame. “It was a bit depressing,” Heinrichs says. “You go to school and you’re told how amazingly inventive and creative you are—then you’re on an assembly line.”

While Disney didn’t wind up using Burton’s quirky, gothic sketches for their next project, The Black Cauldron, Heinrichs was inspired and began to sculpt the characters in three dimensions. “I thought they were very dimensional, but had that wonderful aspect of being very graphic and expressive at the same time,” he says. “In the work I’ve done with Tim, it’s turning graphic work into a kind of immersive world.” Their first film was the 1982 stop-motion animation short Vincent, based on a Burton poem.

The six-minute film tells the story of a young boy obsessed with horror actor Vincent Price. It’s dark and brooding and immediately identifiable as a Tim Burton work, with quirky characters and off-kilter structures.

A few years later, the two were sharing a studio in Pasadena when Burton began sketching scenes from a holiday poem he had written. “I saw this one drawing and almost immediately did a sculpture of Jack [Skellington],” Heinrichs says. He showed it to a stop-motion armature builder, who told him the legs were too thin. “So, I beefed everything up a little bit until he agreed he could make it. It was designed by everybody,” Heinrichs says. “As a result, you’ve got something never quite seen before, and that was a big part of the appeal. I want to work on a movie with other people. The fun is collaborating with them and coming up with something bigger than I could come up with on my own.”

Heinrichs won the Academy Award for Best Production Design for Sleepy Hollow. He created this sketch of the titular town (above). Courtesy of Rick Heinrichs (sketch); Entertainment Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo

EXPANDING THE GALAXY

While Burton’s films tend to occupy a world that is distinctively his, an increasing number of movies build upon existing fictional universes. Sequels, prequels, and reboots are big business, and Heinrichs has helped design some of the biggest—none more prominent than 2017’s Star Wars: The Last Jedi.

Heinrichs spent days in the Lucasfilm archives to prepare. He studied sketches and paintings done by the late Ralph McQuarrie, the conceptual artist who helped define the look of the original Star Wars trilogy in the 1970s and 1980s. “There’s a very identifiable look to the world he created. A simplicity of shape and color and lighting. It felt very modern and futuristic—but also weirdly retro at the same time,” Heinrichs says. His job was to carry that inspiration through a project that included 125 soundstage sets and locations in four countries. “That was the thing that was most exciting—coming up with elements that felt familiar and yet futuristic and cool.”

One of the film’s signature scenes unfolds on the planet Crait. It’s a classic Star Wars battle—good taking on evil against the backdrop of a unique landscape. Rickety Resistance ski speeders charge toward a menacing line of First Order AT-M6 Walkers. Laser blasts and shrapnel slice into the white mineral crust of Crait’s surface, sending red soil exploding into the air. The planet seems to bleed. The scene is reminiscent of the snowy battle on Hoth at the beginning of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, but it also recalls a moment from another Heinrichs film: the blood-covered snow in Fargo’s infamous woodchipper scene.

Heinrichs values his CFA education and the way it helps him interpret a range of artistic influences. For Captain America: The First Avenger, he had decades of Marvel comics to draw on, as well as World War II photographs and propaganda. The challenge, he says, was “the idea of visually presenting this confrontation between fascism and democracy—what are the colors and the shapes that attend to those opposing forces?” For the 2019 live-action adaptation of Dumbo—another Burton collaboration—he cites the painter Edward Hopper as an inspiration. “Understanding how he paints and composes his designs—those things live in your head and they combine with other ideas, and they ultimately come out in a completely different form as design ideas for film.”

Heinrichs also worked with Burton on the 2019 live-action adaptation of Dumbo. © 2019 Disney

YOUNG AT HEART

As formative as BU, CalArts, and Disney were, it’s been his ability to hold on to his childhood passion for creating that continues to fuel Heinrichs. “Nothing compares to your first discoveries and explorations as a kid,” he says. “Tim [Burton] would say that everybody’s an artist when they’re six years old. There is a purity and naïveté and passion to the work you do then. And he would joke, ‘It just gets beaten out of you over time.’” For the partners, success is avoiding that fate.

Heinrichs served as a production designer on the upcoming Amazon Prime Video series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. Watch a teaser trailer here. Video courtesy of Prime Video

Heinrichs can’t say much about his latest projects, Knives Out 2 and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power—both are in postproduction and scheduled for release later this year—but he continues to revel in world building. “It’s difficult to explain to other people how amazing it is to walk onto the sets and see what you’ve been imagining,” Heinrichs says. “It’s one of the reasons I love what I do.”

HEINRICHS’ HIGHLIGHTS

Rick Heinrichs got his start as an animation artist at Disney, but his big break came when he and Tim Burton produced a stop-motion animated short, Vincent, in 1982. The pair have since collaborated on 11 feature films. Heinrichs has worked his way up the creative ranks on both animated and live-action movies, and his design work and direction have enhanced some of the most memorable worlds in film. Here are some of the films that define Heinrichs’ career.

- Vincent (Short, 1982) • Producer, designer, sculptor

- Hansel and Gretel (TV movie, 1983) • Producer, model sculptor

- Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) • Animator, animated effects supervisor

- Beetlejuice (1988) • Visual effects consultant

- Ghostbusters II (1989) • Set designer

- Edward Scissorhands (1990) • Set designer

- Batman Returns (1992) • Art director

- Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) • Visual consultant

- Fargo (1996) • Production designer

- Sleepy Hollow (1999) • Production designer, Academy Award winner for production design

- A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004) • Production designer, Academy Award nominee for art direction

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006) • Production designer, Academy Award nominee for art direction

- Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) • Production designer

- Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) • Production designer

- Dumbo (2019) • Production designer

- The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (TV series, 2022) • Production designer

- Knives Out 2 (2022) • Production designer

“Life Altering”

Amy Sherald’s oil painting She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them (2018).

A Stone Gallery exhibition explores race and racism, identity, and inequity of wealth and power

By Mara Sassoon | Photos by Cydney Scott

The exhibition Life Altering: Selections from a Kansas City Collection, on view at the Faye G., Jo, and James Stone Gallery this past January and February, featured 23 striking works by women, people of color, and artists working internationally. The pieces explored such themes as identity, race, the experience of diaspora, and the impact of technology.

Among the works was New Jersey–based artist Amy Sherald’s oil painting She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them (2018)—the title a reference to a passage in the Zora Neale Hurston novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. In it, a woman with a stoic expression, wearing a bright orange cloche hat, teal shirt, and white floral-patterned pants, faces forward. She is set against a plain coral red background and meets the viewers’ gaze. Sherald has given much attention to the woman’s outfit, capturing the seeming heaviness of the large multistrand pearl necklace she’s wearing. The title of the work pairs with this intense focus given to the woman’s appearance—the viewer is privy only to what they see on the “outside.”

First Lady Michelle Obama selected Sherald to paint her official White House portrait. The painter is also known for her striking portrait of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman fatally shot by white police officers at her home in Louisville, Ky., in 2020. The image was featured on the cover of the September 2020 issue of Vanity Fair. Sherald renders all of her subjects in grisaille—a grayish monochrome—often set against solid color backgrounds, like the painting that was in the Stone Gallery show.

“The story of why I paint my figures gray has evolved over the years. I’m not trying to take race out of the conversation, I’m just trying to highlight an interiority,” she said in a conversation with fellow artist Tyler Mitchell for Art in America in 2021. “In hindsight, I realize that I was avoiding painting people into a corner, where they’d have to exist in some universal way. I don’t want the conversation around my work to be solely about identity.”

Visitors to the Stone Gallery exhibition take in Ethiopian artist Elias Sime’s Tightrope, Familiar Yet Complex 1.

All of the exhibition’s pieces were from the collection of Kansas City art collectors Bill and Christy Gautreaux, who have set out to acquire work by diverse artists. Bill Gautreaux says that collecting these works has been part of “a journey of learning and awareness that has been life altering.” The show featured artists from all over the world and many different cultural heritages, among them Elias Sime, an Ethiopian artist based in Addis Ababa, and Vibha Galhotra, an Indian artist who lives and works in New Delhi. Lissa Cramer (MET’18), managing director of Boston University Art Galleries, worked with independent curator Leesa Fanning to put together the exhibition.

“As with every exhibition at the BU Art Galleries, this show [was] about amplifying the artists’ voices,” says Cramer. “Giving these artists space to make their statement on topics like race, power, and wealth dynamics, and LGBTQIA+ rights—through such dynamic, beautiful works—[was] a timely gift to our BU community as well as to the Boston metro area.”

Explore Life Altering in the virtual gallery walk-through.

Conversation: Emily Deschanel & Daria Polatin

Emily Deschanel ('98), left, and Daria Polatin (’00).

Actor Emily Deschanel and screenwriter Daria Polatin talk about collaborating on the Netflix limited series Devil in Ohio

By Mara Sassoon | Photos by Ben Trivett (Deschanel) and Patrick Strattner (Polatin)

In Daria Polatin’s debut YA thriller, Devil in Ohio, teenager Mae escapes from a satanic cult and moves in with her psychiatrist, Suzanne Mathis. Mae is supposed to live with Mathis and her family for only a few days, but her stay turns longer and longer—to the dismay of Mathis’ 15-year-old daughter, Jules. Mae starts wearing Jules’ clothes, attending her school, and dating her crush. Then, the cult attempts to get Mae back, putting the Mathis family in danger.

The 2017 book is inspired by real-life events. Polatin’s manager, producer Rachel Miller, brought the story to her attention, and she was riveted by the dynamics at play between patient and psychiatrist. “I thought, ‘I need to tell this story,’” says Polatin (’00), an accomplished playwright and screenwriter who has written for Amazon’s Hunters and Jack Ryan. She tracked down and interviewed a source closely involved in the incident and began writing. “A novel seemed like the best format to tell the story initially,” she says. “Novel writing and TV writing are very different. Novel writing can be very interior—you can really live inside the head of the character. But I always had it in the back of my mind to also adapt it for the screen one day.”

In 2019, Polatin began working on a pilot script in earnest. Later this year, Devil in Ohio, a limited series starring Emily Deschanel as Mathis, will begin streaming on Netflix. Polatin, the showrunner and executive producer, and Deschanel (’98), known for her role as forensic anthropologist Temperance “Bones” Brennan on the long-running Fox series Bones, go way back. Both studied acting at BU and quickly became friends while in the program. They reconnected over Zoom in January, just as Devil in Ohio was in postproduction, to discuss their memories of BU, what it’s like playing a man onstage, and how actors and screenwriters can work together to produce great film and TV.

Daria Polatin: Emily, remember when we were in A Tale of Two Cities together at BU?

Emily Deschanel: Yes, how could I forget? Wait, who was the British woman who directed that?

DP: It was Caroline Eves.

ED: Oh my gosh, you have a great memory. I think Caroline Eves directed that junior year Shakespeare project. Was she doing that when you were a junior?

DP: Yeah, I loved the Shakespeare project. It was basically making a new piece by taking story lines from different Shakespeare plays.

ED: Yeah, it was a Shakespeare patchwork quilt kind of thing. And I think it gave the opportunity for women to play a variety of roles. I think we probably both played men quite a bit in college…

DP: Because we’re tall! Yes, I played a lot of men in college.

ED: What men did you play?

DP: I played Guildenstern. We also adapted the book The Awakening by Kate Chopin, and I played the lead woman’s husband—walking stick and all. I can’t remember what else at the moment, but it was definitely a thing.

ED: Oh, that’s fun. Yeah, you played men more than I did. But, you’re how tall?

DP: I’m six feet.

ED: And I’m five-foot-eight. I think I was in an all-female cast in a production of Mrs. Warren’s Profession, but we all played men at some point in that. Such is the experience of a theater student.

DP: I liked it because it was almost easier to dive into something so different. I also liked playing characters with dialects or accents. It helped me embody something different.

ED: I totally agree. It’s fun to dive into a role with a different dialect or accent, or different physical qualities. I don’t get to do that as much now. I mean, I’ve done dialects, but it’s not like in college when it was like, you will play an 80-year-old man with a limp from Austria.

DP: It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period—to get to explore all different kinds of characters and play all kinds of roles without any pigeonholing or judgments. I really loved how intensive it was.

"It was such a great artistic playground to be in during that period."

ED: I also loved the intensity of the program. We were in class from early in the morning through rehearsals late at night. For most of us, this was all we wanted to do. And I guess it prepared us for working in television.

DP: One hundred percent. It prepared us for 18-hour days.

ED: Except it’s a lot easier when you’re 20. Daria, you had told me that [the late CFA professor of playwriting Jon] Lipsky’s class was one thing that made you interested in writing. I want to hear what that experience was like.

DP: He had seen some of my work, and [during] my senior year at BU, he found me in the hallway and said, “You are a writer, and you need to take my playwriting class.” I enrolled, but almost dropped the class because I was so busy. I filled out my drop form and brought it to Lipsky. And I remember he said, “I’m not signing that.” I begrudgingly finished the play, an adaptation of Chekhov’s short story The Lady with the Pet Dog, turned it in, and the school ended up producing it for the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival. It won the regional contest, and then it was performed at the Kennedy Center and got published.

ED: Wow, that’s so interesting to hear. And to think if Jon Lipsky wasn’t your teacher. For the record, I took his playwriting class, and he did not tell me that I am a writer.

DP: Well, I’m glad to know he didn’t just say that to everybody and I just fell for it. [Laughs.]

ED: Do you miss acting at all?

DP: The last play I was in was an Off-Broadway production in the Summer Play Festival. I played an Italian actress/model with this great accent. It was so fun. But after that I was like, “I’m done.” I haven’t really looked back. Acting onstage made me very nervous. There’s no net—if you forget your lines, what do you do? I enjoyed it, but it gave me a lot of anxiety. Not that writing doesn’t give me a lot of anxiety.

ED: It’s funny because those kind of moments—being onstage or on set and you forget a line or someone else forgets a line, and you don’t know what to do next—they terrify the hell out of me, but they are also some of my most favorite moments in acting. It’s this crazy thrill of anything could happen. I thrive on that. I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it.

DP: Well, you’re very good at it. How did you find transitioning from mostly doing theater in school and then moving into TV and film?

ED: I didn’t have that transition some people have where they’re in New York doing theater first, even though theater was my first love. But I realized that there were so many more opportunities for me as an actor in LA. I found a manager in LA and then I started auditioning for film and TV roles. A few months later, I got my first job, a Stephen King miniseries called Rose Red. Scary stuff. I actually still use some of the script analysis things we learned at BU, and I think it’s helpful to have the background I got from BU to play different parts.

DP: The script analysis classes were so good at BU. I learned so much about storytelling and breaking down a story. I think what that gave me as a writer are the tools to know the kind of information the actor needs—the character’s motivations, backstory.

ED: Yeah, and us actors appreciate that. You can make lines work, but when you have the background to understand why you’re saying what you’re saying, it makes a huge difference. I’m thinking of our time on set. I got as much information as I could from you, both on the real story and your novel. I feel like I was always hounding you to give me more and more information. What was it like making your own book into a TV series?

DP: I have adapted other books for TV before. I worked on Jack Ryan for two seasons and the season of Castle Rock that adapted Misery and tells the Annie Wilkes backstory. But getting to adapt my own novel was so interesting. I just knew the characters and the world so intimately. For the TV version, we really wanted to go into it primarily through Suzanne’s eyes and experience the story from Suzanne’s perspective. Why does Suzanne take this girl home? Why does she want to help her?

ED: I found that fascinating too. It was really helpful that you had so much time with the characters and the story from writing the book and writing the series.

"I totally get the anxiety-producing part of acting, but I somehow love it."

DP: When you’re storytelling, it’s not only about what you’re showing, it’s also about what you’re not showing. So knowing what you’re not showing is helpful and adds that extra layer to creating well-formed characters whose world you’re just happening to get a glimpse into certain parts of.

ED: That’s a good point. There are always things the audience is not seeing. That’s so interesting to think about. Do you want to write another novel?

DP: I do. But novel writing is extremely time-consuming, and I’m always thinking about what medium is best for a story.

ED: A novel is no joke. I mean, not that TV writing is an easy feat in any way.

DP: It’s all very time-consuming. It just takes so much physical and mental energy when you’re really giving your all to a project. You spend years working on these things, so it has to be something that continues to bring you joy and be interesting. I first started the pilot with Netflix, like, three years ago at this point.

ED: And when did you start writing the novel?

DP: I think in 2013. The novel came out in 2017. All in all, with the show coming out, it’s been almost a 10-year process that the story has lived through.

ED: I think it’s interesting for people to understand how long some of these things can take. That’s not always the case. Most of my career was in network series. So it was grind, grind, grind. Sometimes I’d finish an episode and it would air, like, two weeks later.

DP: Oh wow! One of the advantages to writing a show for a streaming service is that usually you will finish writing the season before you film it. Of course, there are always things that you learn on set, and you still have to pivot for all the production issues, like weather…

ED: Weather? What? [Laughs.] Yeah, we definitely had to deal with our share of weather in Vancouver while shooting Devil in Ohio. Some bomb cyclones, atmospheric rivers…

DP: Snowstorms.

ED: That was nerve-racking when it snowed because it wasn’t going to match what had already been shot, and there were these consecutive things that we had to shoot.

DP: Yeah, we had to heat blast an entire field to get rid of the snow. It was a fast shoot.

ED: It was so great to have this shorthand with you on set, Daria. It was like, okay, we know each other. Let’s just dive into the work part.

DP: And you brought such a beautiful, intense focus to this role, and really graceful empathy to this character.

ED: Thank you. That’s very kind. It was really lovely to work together after so many years in such a different way than doing A Tale of Two Cities at BU.

DP: We’ve come a long way since A Tale of Two Cities.

Broadway is Back

As casts and crews return to the stage, many productions want to flip the scripts—to right systemic wrongs

By Mara Sassoon | Photo by Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

Walk around Manhattan’s Theater District these days and it may seem as though nothing has changed since the pandemic forced Broadway to go dark for 18 months beginning in March 2020. In the afternoon, a line of people hoping to snag discount tickets to a show snakes around the TKTS booth and its iconic red steps in the heart of Times Square. That evening, a throng of eager theatergoers waits to be let into the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre to see the Tony Award–winning singer and actor Patti Lupone in the revival of Company.

But look a little closer, and it’s clear that things have changed. Many people in the TKTS line wear masks. While they no longer check for proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test as of May 2022, theater personnel at the doors of the Jacobs continue to remind everyone in line that they must wear their masks throughout the entire performance.

Still, inside the Jacobs—or any of Broadway’s 41 historic theaters during those magical minutes before the lights dim and the production starts—audience excitement is palpable. A group of friends huddles together in their seats, giddily clutching their playbills and smiling behind their masks for a quick selfie. Others take in the intricate details of the theater. More than once someone says, “I’ve missed this.”

People line up outside the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre for a performance of Company in January 2022. Until May 2022, theatergoers had to show proof of vaccination or a negative COVID test to see a Broadway production. An Rong Xu/The New York Times

Yes, things are a little different, but Broadway is back after its longest break ever. A typical season might include 30 to 40 plays and musicals—both originals and revivals—that employ almost 100,000 people locally. The 2018–2019 season brought in almost $1.83 billion and was the highest grossing season in Broadway history, according to The Broadway League.

Since September 2021, more than 30 productions have opened or reopened, including Company, Funny Girl, and The Music Man. The musical Mrs. Doubtfire, which had only a few days of Broadway previews before the shutdown, resumed previews in October 2021 and officially opened two months later, although it faced a couple of COVID-related hiatuses and an early closure.

"Jeez Louise, was it emotional. We’re performers, so we’re inclined to be perhaps a little more dramatic. But I was unprepared for the swell of emotion being up there together again."

“It’s been a wild ride,” says Brad Oscar, who played Frank Hillard, the brother of Daniel Hillard (aka Mrs. Doubtfire), in the musical. Oscar (’86), a Tony Award–nominated actor who starred as Nostradamus in the original Broadway production of Something Rotten!, spoke with CFA in December 2021, at the tail end of Mrs. Doubtfire’s first four-day hiatus following multiple positive COVID tests in the company. “It’s frustrating because we’re playing a game of stop and start,” he says. “But even through these hiccups, we are back and we’re going to get through this.”

Despite the hardships that Mrs. Doubtfire and other shows have experienced, many have characterized the pandemic-induced pause Broadway went through as a much-needed opportunity to reconsider its systemic issues, including pay parity and diversity, equity, and inclusion. In November 2021, the New York Times reported that some plays and musicals, including The Book of Mormon, The Lion King, and Hamilton, “are making script and staging changes to reflect concerns that intensified after last year’s huge wave of protests against racism and police misconduct.”

Tony Award–nominated actor Brad Oscar (’86), at left, played Frank Hillard in Mrs. Doubtfire. Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

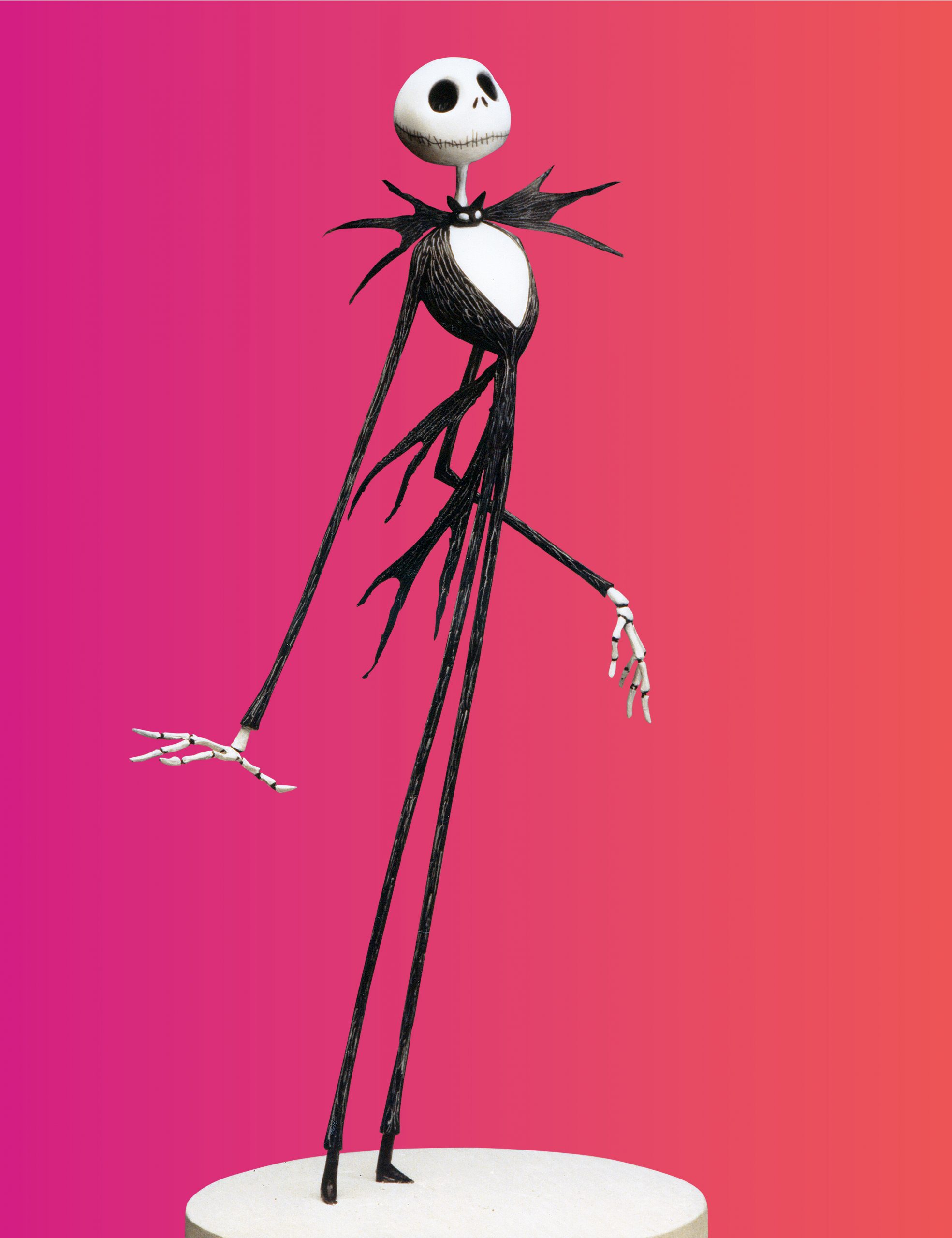

“I think it’s time the theater and film industries get with the program and realize that there are all sorts of truly brilliant actors out there who can play any role,” says Tony-winning producer Fred Zollo (CAS’75), who coproduced the Broadway revival of Macbeth, starring Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga. The production, which premiered in March 2022, is notable for its inclusive creative team and casting, including actor Amber Gray (’04) in the traditionally male role of Banquo, and the nonbinary actor Asia Kate Dillon as Malcolm. “It’s taken us a very long time—way too long,” says Zollo, “but we are finally starting to see productions taking this view.”

“It’s Gonna Be All Right”

A few weeks before Mrs. Doubtfire reopened on Broadway in December 2021, the cast appeared on Good Morning America to sing one of the show’s playful songs, “Bam! You’re Rockin’ Now.” At the end of their performance, they segued into a peppy riff on the musical’s closing number, “As Long as There Is Love.” Their words rang like a resilient battle cry: “It’s gonna be all right—as long as there is love.”

The show finally had its opening night on Broadway on December 5, 2021.

“Jeez Louise, was it emotional,” Oscar says. “We’re performers, so I think we’re inclined to be perhaps a little more dramatic. I knew I missed performing because this is such a part of who I am—it feeds my soul. But I was unprepared for the swell of emotion being up there together again.”

Watch Brad Oscar and the cast of Mrs. Doubtfire perform on Good Morning America in November 2021. Video courtesy of Independent Musicians Foundation

After it returned to Broadway, Mrs. Doubtfire followed intense COVID protocols, including working with an outside company to manage its staff testing program, and having two compliance officers at the theater each day to ensure theater staff and audiences adhered to masking, testing, and vaccination requirements. Oscar says he went to the theater every day to get tested.

Even so, not long after its short December hiatus, as Omicron cases rose, Mrs. Doubtfire’s creative team made the difficult decision to pause the show temporarily, from January 10 until April 14, 2022, promising to rehire everyone who wanted to return after that time. Lead producer Kevin McCollum told the New York Times that shutting down the production for that period would ultimately save it from running out of money. The Times reported that the show’s expenses ran close to $700,000 per week, regardless of whether performances took place. “My job is to protect the jobs long-term of those who are working on Mrs. Doubtfire, and this is the best way I can do that today,” McCollum told the Times. But by mid-May, he announced the show would have to close at the end of the month—three months early—because sales hadn’t improved enough. The musical still has plans for a month of performances in the UK in fall 2022 and a US tour beginning in late 2023.

Coming Back, Moving Forward

While Broadway shows are still contending with how to handle pandemic-related disruptions, they are also examining how to grapple with some long-standing problems. “We acknowledged that, yes we’re back, but let’s just not come back to where we were, let’s move forward,” says Oscar.

"The fact that we’re opening the door to writers, actors, and artists from everywhere—it only enriches the theater."

Even before the pandemic and the racial reckoning of 2020, the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion was a primary concern for many in the theater industry. The labor union Actors’ Equity has published a series of reports on these topics since 2017. In 2020, they released a diversity and inclusion report that looked at the demographics of its members from 2016 through 2019. In an opening letter to the report, Actors’ Equity executive director Mary McColl noted that while there had been some progress, such as more contracts being given nationally to women and people of color, “these gains have been woefully insufficient, and not uniformly true across the country.” The report found that of the total Equity contracts nationally—including principal, chorus, stage manager, and assistant stage manager contracts—63.95 percent were given to people who identify as white. “Among production contracts,” the report said, “much of the increased representation of people of color can be attributed to multiple productions of Hamilton alone.” The report also called out that “barely” one percent of contracts were given to members with disabilities.

“I think we’ve always been aware of the issues of representation in theater,” says Oscar, “but it continues to happen. And you think, ‘How does this continue to happen?’ I’m hopeful that something just broke—in a good way—and we make real change. It broke because it’s been breaking for, well, centuries.” He says Mrs. Doubtfire’s creative team made sure that the cast and crew attend a series of diversity trainings before diving into rehearsals.

Casting director Tara Rubin says that representation is at the center of every project she works on now. “It’s the first conversation we have, and it’s no longer a goal—it’s just a given,” says Rubin (CAS’77). “We didn’t do a good enough job in the past.”

Improving representation onstage begins with those who are doing the casting—a field distinctly lacking in diversity, says Rubin. “But I’d say there is an industry-wide consideration and movement toward improving that,” she says. The professional organization Casting Society of America launched a training and education program for young people who are interested in the field, with the goal of helping BIPOC students jump-start their careers. Rubin says that she and her colleagues also participate in a mentorship program with the goal of helping underrepresented groups break into the casting world. “We’re really training our eyes on how we can improve our own industry and create a viable pipeline for people.”

Oscar is upbeat about the changes he’s seen. In the two years prior to the pandemic, he performed in three regional plays that featured “the most diverse group of actors that I’ve ever worked with. I’m a white, middle-aged, Jewish gay man, but in all three of those productions, I was a minority. And I thought, ‘Isn’t that cool?’”

The Broadway revival of Macbeth is notable for its inclusive casting, including actor Amber Gray (’04), in the traditionally male role of Banquo. Greg Allen/Invision/AP

Harvey Young, dean of the College of Fine Arts, also says he’s observed “a sea change in artistic leadership [in regional theater], with more women and people of color appointed as executive or artistic directors.”

“The lineup of plays, playwrights, and productions [in regional theater] has never been more representative of the US,” says Young, a nationally recognized theater educator and a member of the College of Fellows of the American Theatre. “The single ‘diversity slot’—for a woman and/or person of color playwright—in a season has multiplied.

“What hasn’t changed, or has been slow to change, is the makeup of theater audiences,” says Young. “There is still more outreach needed to make theater accessible and affordable to more people.”

Some strides in improving accessibility of productions have been made, including presenting shows in new, experimental formats. Young points to the success of Ratatouille: The TikTok Musical and the Pulitzer Prize nomination for the online play Circle Jerk as signs that people are beginning to embrace alternate ways to attend and experience theater. Jeremy O. Harris, who wrote Slave Play, helped produce livestreamed productions of both plays.

Zollo, the producer of Macbeth, has made it a goal to improve the accessibility of his productions. The show had a Macbeth 2022 program designed to provide at least 2,022 tickets to students, with the goal of reaching students who are underrepresented on Broadway, including from BIPOC communities and those with disabilities. “We want[ed] everyone who want[ed] to see this production to have the opportunity to do so,” Zollo says.

Rubin hopes the industry continues to improve on another pressing issue: pay parity. “I would like to make sure that even though we’ve come back—and we’re all very proud of that, and it’s been incredibly hectic—that we don’t take our eyes off the big prize,” she says. “It’s time to really look at some of our financial models and pay structures for all of the departments in creating a theater production.”

Actors’ Equity, in a 2020 hiring bias report that it published in 2022, looked at the industry’s pay statistics in the three months before the pandemic shutdowns and found that “men still earn more than women on average across nearly every job category, and non-binary members tend to earn less than men or women.”

Though there is still a long way to go, Zollo, who has produced more than 100 plays and won seven Tonys in his 40-year career, says the initiatives that are being taken lately have given him hope for better inclusivity across all aspects of productions. “The fact that we’re opening the door to writers, actors, and artists from everywhere—it only enriches the theater.”

Solar Art

Laura Blacklow blends traditional photo techniques with modern messages to create the books in her Quarantine Project

By Marc Chalufour | Photos by Conor Doherty

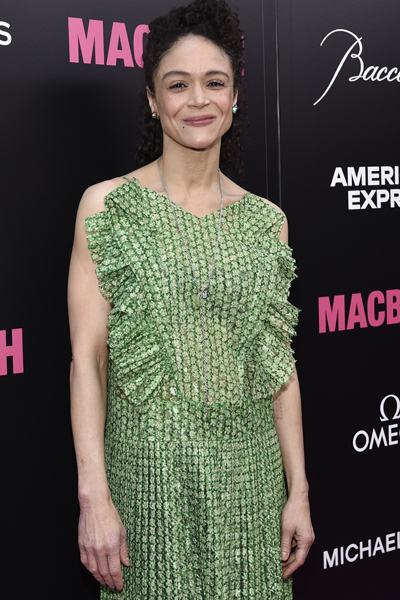

Blacklow prepares a solution she’ll use to coat her paper for a cyanotype.

Laura Blacklow learned photography long before the advent of digital cameras, but the Cambridge, Mass.–based artist never developed a fondness for working in a darkroom. Instead, she gravitated to processes like cyanotype and Van Dyke brown printing that she could do outdoors. “I just come alive when the sun comes out,” she says.

Those classic sun-printing methods are also conducive to experimentation. Blacklow (’67) has printed onto paper and textiles, and she’s created images with both photo negatives and three-dimensional objects. Developing the prints is often just the first step. She might color them with pastels or watercolor paints, sew them, or fold them into unique artist’s books.

Both artist and activist, Blacklow often blends words and images to convey a message in her work. She’s made prints with native rainforest plants to highlight the plunder of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala and with plastic toy soldiers to expose violence against the Maya. For the past two years, Blacklow has drawn inspiration closer to home—pulling words from her readings, objects from her home, and flowers from her garden, she has created a series of accordion-fold books that she calls her Quarantine Project.

“The Best of Multiple Art Forms”

To make a sun print, she lays the coated paper and objects she plans to print on a tray, covers them with a sheet of glass, and carries it all outside.

As a kid growing up in Washington, D.C., Blacklow followed the work of Jacqueline Bouvier, a photographer and columnist for the Washington Post before Bouvier married John F. Kennedy (Hon.’55). CFA didn’t have a darkroom when she attended, so Blacklow studied painting and drawing, then trekked down Comm Ave to take a photojournalism course at the College of Communication. A Robert Rauschenberg exhibit at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art during her senior year made a lasting impression.

“This man was combining photography with painting. I know it wasn’t journalism in the strict sense, but he was making statements about being alive,” she says. “He just knocked me out.” Blacklow began melding mediums and hasn’t stopped. More than five decades later, she still considers Rauschenberg her biggest influence—although the form that she has devoted most of her career to isn’t framed prints meant to be hung on a wall. “I’m not a person who needs to make heroic, large artwork,” she says. “I like little, intimate messages.”

To Blacklow, a book represents the best of multiple art forms. Each page can be observed alone, like a photograph or painting, while the book itself occupies three dimensions, like a sculpture. And the physical act of studying and turning the pages takes time, like viewing a film. “There’s such an intimacy there. You can hold it in your lap. You can leaf through it frontward and backwards,” she says.

The Quarantine Project

The pandemic cut Blacklow off from her usual sources of inspiration: traveling and doing deep archival research. Quarantined at home, she tended to her flower garden where she grows hibiscus, lilies, astilbe, hosta, ferns, iris, daffodils, tulips, crocus, bleeding hearts, wisteria, and cohosh. She cleaned out her grown son’s old closet and discovered a box of his high school English books and began reading, for the first time, James Baldwin, Nadine Gordimer, and James McBride.

Sometimes, she’ll use an indoor artificial exposure unit to make her prints if there is not enough sun outside.

The words of others help Blacklow process world events. “I’ve been an avid journal keeper since I was a child,” she says. “I write down quotes, I write down dreams.” With the pandemic worsening and amid the national reckoning over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, she decided to share some of the quotes she found most helpful. “It’s so hard to have hope sometimes. And I’m an optimist,” she says.

Blacklow began pairing quotes with plants from her garden or other objects found around her house, like old locks and keys, and making sun prints in her yard. Quarantine Project captures a vision of the pandemic that’s uniquely her own. Blacklow has produced more than a dozen one-of-a-kind books, drawing from sources as disparate as Native American proverbs, the late congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis (Hon.’18), 13th-century Persian poet Rumi, and contemporary Russian poet and mystery writer Elena Mikhalkova.

Each book is formed by a single sheet of folded paper that opens to reveal a print Blacklow created by laying objects and sheets of acetate, with words written on them, over light-sensitive paper.

Blacklow is quick to point out that she often employs more modern methods in her art. “I want to be really clear about this—I’m not a Luddite,” she says. When the first color Xerox machines were introduced, Blacklow printed onto the thickest paper its rollers could handle without jamming. She’s printed onto satin, which she had to stiffen with spray-on starch, experimented with Polaroid cameras, and embraced digital photography. “Spending a day in the darkroom with a red light is not my favorite thing,” says Blacklow, author of New Dimensions in Photo Processes: A Step-by-Step Manual for Alternative Techniques (Focal Press, 2018), now in its fifth printing. “What took me a day, I can do in 15 minutes with Photoshop and an inkjet printer.”

Inside her studio, she removes the objects and then rinses the paper in water to halt the cyanotype’s development process. “Cyanotype is my favorite because it’s the least fussy,” she says.

Photographers typically use paper that’s precoated with emulsion, but Blacklow likes to have more control over the surfaces she prints on. Her work begins in the renovated carriage house behind her home, where she has a studio and darkroom. If she’s making a cyanotype, she adds water to a mixture of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to create an emulsion and, with the lights dimmed, brushes it onto sheets of paper—often a high-quality cotton rag stock. Then she hangs the sheets to dry or, if she’s in a hurry, uses a hair dryer. For Van Dyke brown, the emulsion is slightly different: water, ferric ammonium citrate, silver nitrate crystal, and tartaric acid.

“I Love the Accidents”

Blacklow’s process of making a sun print is as crude as the results are delicate. She lays a sheet of coated paper and the objects she plans to print on a tray, covers them with a sheet of glass, and carries it all outside. For large prints, she arranges everything outside, shielded from the light by a tent she made by stretching black mulching plastic over a wood frame. Then she whisks away the plastic tent and watches her images develop.

"I just come alive when the sun comes out."

On her cyanotypes, the sharp contours of leaves, delicate petals, and skinny stems appear in shades of white against a deep blue background. Imagine a blueprint of a wildflower garden—cyanotype is the same process once used by architects to develop their plans. Van Dyke brown prints offer a more organic look, mixing golden yellows and browns.

When Blacklow makes a cyanotype, she may let it sit for an hour, an overexposure that creates a deep blue, as in Sonny’s Blues. The 12-panel accordion book features words from James Baldwin’s short story of the same name. Image courtesy of Blacklow

Blacklow doesn’t set a timer for her outdoor exposures, but watches them until she’s satisfied. The duration can vary greatly depending on the time of day, temperature, and cloud cover. A cyanotype may sit for an hour, a deliberate overexposure that creates a deep blue that Blacklow especially loves. She rinses the paper to halt the process: just water for a cyanotype, or a chemical fixer commonly used in photography for a Van Dyke brown. “Cyanotype is my favorite because it’s the least fussy,” she says.

Inherit the Earth, a Van Dyke brown print, uses a Native American proverb. Image courtesy of Blacklow

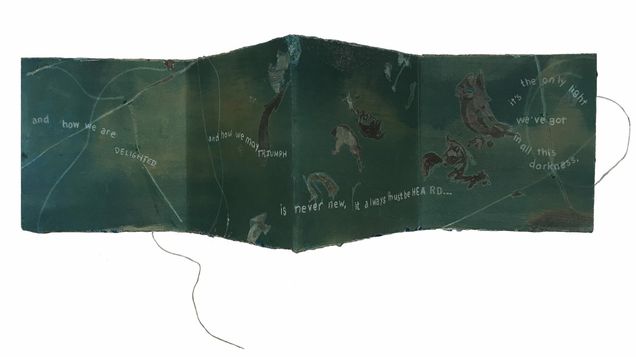

In Sonny’s Blues, a 12-panel accordion book, the paper is a deep blue-green, mottled with white that looks like clouds on an ominous day. Leaves seem to float in this fantastical sky. James Baldwin’s words, from a short story of the same name, flow across this scene: “The tale of how we suffer, and how we are DELIGHTED and how we may TRIUMPH is never new, it always must be HEARD…it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.”

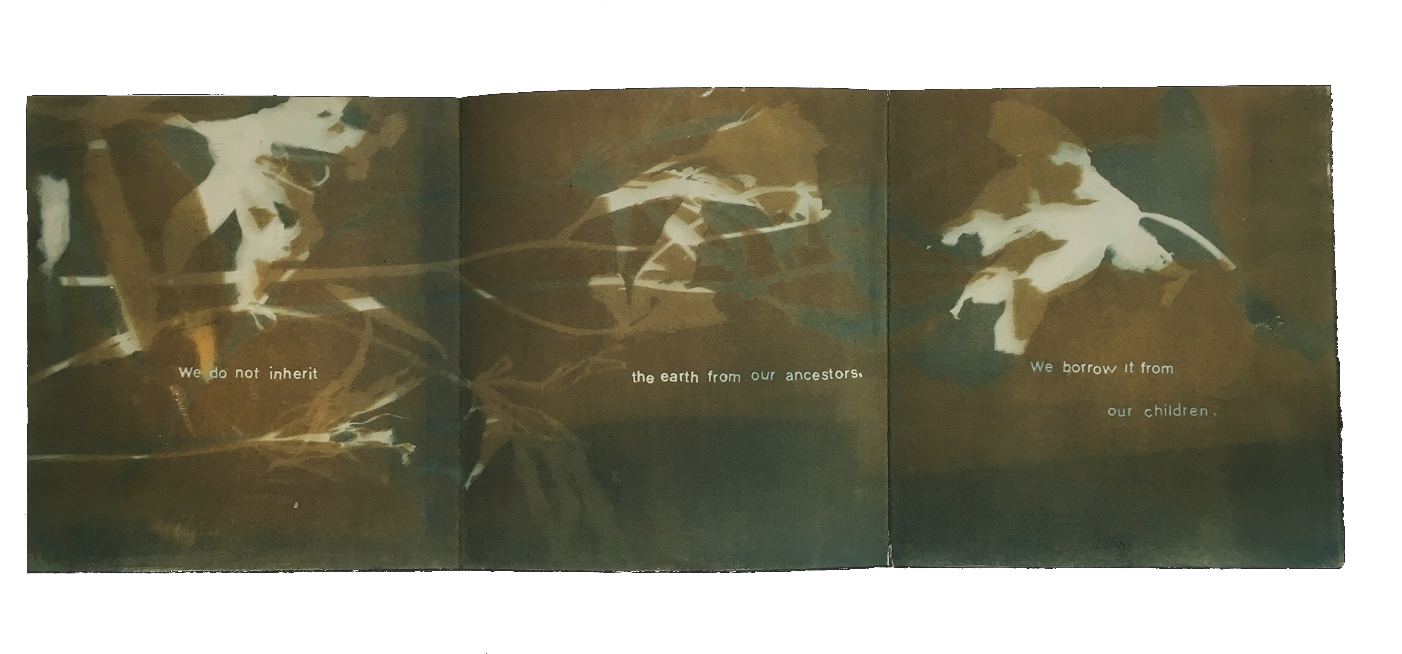

Inherit the Earth, a Van Dyke brown print, uses a Native American proverb: “We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors. We borrow it from our children.” A cluster of flowers—stems, petals, and all—reach across the page, parallel to the words. Each is rendered in shades of yellow and brown. They look burned onto the page, which, in a way, they are.

Part of Blacklow’s continued fascination with sun printing is that she never knows exactly what she’ll end up with. “I love the accidents,” she says. She doesn’t consider photography to be an exact representation of reality. “Just the fact that the three-dimensional world is translated onto a flat surface changes what you see.”

New Master’s in Fine Arts: Print Media and Photography

A form of art Laura Blacklow has spent her life on is now an MFA program. Beginning in fall 2022, CFA will launch an MFA in print media and photography. “This is a degree that bridges these two mediums,” says Lynne Allen, a professor of printmaking and director of the new program. “Printmaking and photography have much in common, including various techniques and the ability to make multiples. Bookmaking can also be a large part of a student’s oeuvre, and we encourage experimentation. I’m excited because this allows for a wider discussion about contemporary art—and print and photo’s place within it.”

Learn about CFA's new program merging printmaking and photography practices.

The Music Pioneer

Mari Kimura came to BU to study violin performance and left as an innovator at the intersection of art and technology

By Joel Brown | Photos by Conor Doherty

Mari Kimura grew up outside Tokyo in a solar house, one of the first in Japan. Her father was an architecture professor and a solar energy pioneer, always experimenting, and when she was little, the 1973 oil crisis made him famous and drew TV cameras to their home.

One day, “I remember so clearly playing outside in the cold winter light with a friend, and my shadow was very long,” says Kimura (’88). “I saw the shadow of my house, and there’s this sort of arch that shouldn’t have been there. So I look up, and it’s water gushing out of the solar panels because the pipes froze and erupted. I rushed into the house to tell my father, ‘There’s water coming out of the house! You have to go up on the roof and fix it!’ I was beside myself. And to my astonishment, he ran around the house shouting, ‘Where’s my camera?’ Fixing was not his priority—he had to document it.

“I grew up like that,” says the violinist, composer, and tech innovator, smiling. “Experimenting was in my blood, in a way.”

Now a professor of music in the Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Technology program at UC Irvine’s Claire Trevor School of the Arts, she is renowned as a violinist, performing with symphonies around the world, as well as for her innovations in “subharmonics,” a special bowing technique that produces notes an octave below the violin’s lowest string. She was invited to join the faculty at UC Irvine in 2017 in large part because of her growing use of digital technology, particularly motion detectors attached to her bow hand. The feedback she gets from the sensors—metrics such as the angle and acceleration of her arm—guides her own performances or the sounds, lighting, and projections that accompany them, and drives collaborative works with other artists.

She even has her own one-woman company, Kimari LLC, to develop and market her patented motion sensor, called MUGIC® (Music/User Gesture Interface Control), worn by her students at UC Irvine and the summer Atlantic Music Festival in Maine. The Wi-Fi sensor can create sounds, change lighting, and generate and control visual effects. Kimura wears the device in a glove on her bow hand; others attach it to their instruments or to wristbands or ankle straps or anywhere else that provides relevant data. The sensor is being used at institutions such as Harvard, Juilliard, and the University of Chicago.

"Experimenting was in my blood."

“Technology works for her in the same way it has worked for great artists for thousands of years,” says John Crawford, a professor of intermedia arts at UC Irvine who’s been collaborating with Kimura since he helped recruit her to the school. “At one point, the violin she plays now was seen as cutting-edge technology. They had to not only invent it but invent methods of playing. She finds ways of adapting technology to her own creative pursuits.

“The MUGIC device is a perfect example,” Crawford says. “People have done different kinds of motion tracking before, but she has found a way to harness the capabilities of these little chips and batteries and pieces of plastic to create new forms of expression. It’s extremely influential, really interesting, and a lot of fun to work together on.”

Violinist and composer Mari Kimura developed and patented MUGIC® (Music/User Gesture Interface Control), a Wi-Fi motion sensor musicians can use to create sounds, change lighting, and generate and control visual effects.

Kimura also has intellectual roots in the culture of innovation around Boston and Cambridge. Her parents met as Fulbright Scholars on a ship coming to the US; her father, Ken-ichi Kimura, was headed to MIT, and her mother, Aiko Kimura, a social scientist focusing on women’s labor laws, to Mount Holyoke and later Radcliffe. They married in the MIT Chapel, and returned to Japan when Aiko was pregnant. Kimura was born in Tokyo.

Kimura graduated with a degree in violin performance from Toho Gakuen School of Music in Japan (which also counts former Boston Symphony Orchestra music director Seiji Ozawa among its alumni) and came to BU to earn her master’s, studying under Roman Totenberg, the late CFA professor emeritus of music and a friend of her undergraduate mentor in Japan. She went on to receive a doctorate in musical arts from Juilliard.

Kimura’s interest in the intersection of music and technology, she says, began in earnest at BU—on and off campus.

To fulfill a requirement, she took an electronic music class, in which she was the only woman, she says. Samuel Headrick, a CFA associate professor of music, composition, and music theory, introduced her to a whole new world of sounds that were then produced largely by analog synthesizers.

While studying at CFA, she rented a room on Carlton Street in Brookline, near the BU Bridge. She was drawn into the social circle of Marvin Minsky, the late MIT computer scientist and a force behind that school’s artificial intelligence and media labs, who lived nearby on Ivy Street.

“I didn’t know how famous he was or anything, but I started hanging out in his kitchen,” Kimura says. “I got exposed to all these AI people and creative minds. And he said, ‘Oh, so you’re a violinist? What are you going to do if you lose your hand? You should start composing.’ And I’m like, ‘Who is this crazy person?’”

Together, Headrick’s class and Minsky’s prodding changed the course of her career. She learned about the groundbreaking work of the late Mario Davidovsky, a professor of composition at Columbia who became known for pairing electronic sounds with acoustic chamber music. She began integrating electronic elements into her own compositions and performances. She was eventually recruited to teach at Juilliard and NYU and was a visiting researcher at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics.

Along the way, she met and married a French mathematician and computer scientist, Hervé Brönnimann, who works in the hedge fund industry. Their daughter is a psychology student at UC San Diego, and their son joined the US Army Reserve this past year after graduating from high school.

Her work bringing the MUGIC to market has led her to pursue an executive MBA at UC Irvine, and her student cohort includes several veterans who, she says, “became a support group for me, the mom, saying, ‘Day or night, you can call us.’”

Kimura says she had moments early in her career where as a woman she may have been held back by the culture of the field. A white, male, prominent professor asked someone, ‘Who programs Mari’s sounds?’ thinking I wouldn’t be able to do it myself. I don’t think it was gender prejudice. It’s more like, ‘How can a violin player program for herself?’ The friend who got asked was more upset than I was.

“I have this image in my head of myself: I’ve been doing this very unusual thing for a classically trained violinist, and I have to have this huge machete to cut through the jungle and carve out the road I want to walk on,” she says. “So I thought, if I give machetes to five other people and we do this together, then the people behind us can go further and faster. That’s why I teach.”

Banish the Butterflies

Pianist Matthew Xiong helps musicians overcome performance anxiety

By Pamela Reynolds | Illustrations by Lydia Ortiz

By the age of 11, pianist Matthew Xiong could ascend a stage, calmly survey a sea of expectant faces, and, unperturbed, skillfully sail through Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1. For Xiong (’20), playing in front of an audience was exhilarating. Then one day in his early teens, he sat down at the piano at a high-pressure national music competition in his native Australia to perform his beloved Liszt concerto.

He froze.

“I had already been in quite a few competitions by that time, so I was not unfamiliar to the pressure,” he says. “But that competition, I felt extremely nervous. I had a gigantic memory lapse onstage, and it was just unrecoverable—and extremely humiliating.”

From that point on, Xiong was plagued by a dread of performing, something he describes as a “mild form of PTSD.” He carried on with his career, but before performances he would shake uncontrollably and his diaphragm would seize up.

“I would go onstage, and I’d be like, ‘Why am I so cripplingly anxious about this when I love performing and I love playing music?’”

The search for an answer to that question has brought Xiong to where he is today—a music instructor dedicated to helping other musicians overcome potentially career-killing performance anxiety.

Matthew Xiong (’20) works to help musicians manage performance anxiety. Courtesy of Xiong

Xiong teaches at two Boston-area music schools—Talent Music Academy in Brighton and Merry Melody Music Academy in Westwood. He says that traditional advice about overcoming stage fright—practice, practice, practice or play more public concerts—doesn’t begin to account for the complex interplay of factors leading performers to quake in fear onstage. Sometimes performance anxiety can be triggered by one bad performance, like his. Other times it can be related to deeper psychological issues. Sometimes anxiety can be intense and paralyzing, akin to a panic attack, Xiong says, or it can be the racing heartbeat that many of us feel when all eyes are on us.

His assessment is backed by research in the area, says Karin S. Hendricks, an associate professor of music and chair of music education. For example, some studies have suggested that musical performance anxiety is predicted by depression and certain anxiety disorders. Culture, genetics, and even nutrition can also play a role.

“Every one of us has such a complex and unique system of experiences and influences in our lives,” says Hendricks, who coauthored Performance Anxiety Strategies: A Musician’s Guide to Managing Stage Fright (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). “It’s really not just one thing that causes performance anxiety. We have influences from parents, teachers, experiences, but then we also have our own internal processes. And these all influence us to have our own recipe for anxiety. We call it performance anxiety or stage fright, but even that means something different to every person. What may be butterflies to some people, getting them excited to go onstage and jazzed up to give a marvelous performance, can paralyze another person.”

Karin S. Hendricks, an associate professor of music and chair of music education, is the coauthor of Performance Anxiety Strategies: A Musician’s Guide to Managing Stage Fright (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). Courtesy of Hendricks

For years after that failed performance, Xiong sought advice from musical mentors about what he might do to quell his paralyzing fear. Everyone told him that he shouldn’t worry, since he’d practiced so much. Their gentle admonishment: just don’t be nervous, you’ll do fine.

“That was really easy for them to say,” he says, “but what could I actually do to not be nervous?”

It wasn’t until Xiong, who received a master’s in music performance at BU, became a music instructor that he moved closer to figuring out how to help others with performance anxiety.

“It was actually when I got into teaching that I realized I need to solve this problem because I’m seeing this in my students and they’re suffering too,” he says. “It breaks my heart. I can see how I was in those situations. It only takes one bad performance experience for them to spiral into the void.”

Xiong began intense research and came across the work of Noa Kageyama, a performance coach at Juilliard, who advocates “centering” as a way of productively channeling nervousness. He combed through studies in the areas of anxiety and sports psychology. He discovered the concept of “flooding” or desensitizing phobia patients by immersing them in anxiety-provoking situations. He knew that such a model of treatment would not translate well to the stage, where anxious musicians are likely to feel even worse after a jittery performance, thereby reinforcing their anxiety.

“It just ends up being catastrophic,” Xiong says.

Over time, he developed his own methods. Rather than desensitize students to their performance fears, he allows them to decide for themselves exactly how much pressure they are willing to put themselves under. At first, they may play only in front of Xiong. Then they might choose to add another student or two. As time passes, they might grow their audiences little by little.

“Anyone could benefit with the kind of incremental exposure that I do with my students when they feel a sense of anxiety,” says Xiong, who has developed several other strategies for conquering stage fright. (For more of them, read “Five Steps to Help Manage Performance Anxiety,” below.)

“If they’re trained in that from the get-go, even if they have a catastrophic experience, they won’t fall into that ‘I’m having a post-traumatic stress response to this.’ They already have the tools to deal with it.”

Five Steps to Help Manage Performance Anxiety

If you experience stage fright before a big performance, pianist and music instructor Matthew Xiong (’20) and Karin S. Hendricks, an associate professor of music and chair of music education, offer suggestions to alleviate that anxiety

Take a holistic approach

Manage stress and maintain good health even offstage. That means eating well, exercising, getting enough sleep, and engaging in mindfulness practices such as meditation, deep breathing, and yoga.

“It’s most helpful to practice mindfulness in everything you do so it becomes a part of your disposition,” says Hendricks, “rather than just a Band-Aid you put on before you perform.”

These mindfulness practices also help build the awareness a performer needs to recognize tension. Once performers are aware of their tension, says Xiong, they can experiment with exercises to release it. One of Xiong’s favorites is to have students assume a floppy, marionette-like posture.

“This is what it feels like to be fully relaxed,” he tells students. “They have to recognize that there’s a different sensation first.”

Practice self-awareness

Xiong leads his students in exercises meant to address the gnawing physical symptoms that can impede a performance.

“The most important step to conquering those physical symptoms is actually just becoming self-aware,” he says. “Often in the moment, we’re not aware because we’re in fight or flight mode. When you tighten up your stomach, when your shoulders go up, when your breathing starts to get really shallow and labored—we’re not conscious of those things because we’re so afraid of the situation.”

When Xiong notices those symptoms, he asks his students to stop playing and acknowledge them as well.

“In piano, as soon as that tension occurs in your arms, you can’t play,” he says. “There’s no way for you to continue that free flow of music coming out of you. I can hear it in the playing. It’s not just a visual thing.”

Challenge negative thoughts

“Just like we practice our art and craft, we have to practice positive thoughts,” says Hendricks. “We have to unpractice negative thinking. The first step is noticing what we’re thinking, noticing what we’re feeling. For so many of us who were trained in classical music, it’s all about this level of heightened perfection. You’re so into getting everything right, but then you become afraid of getting things wrong, including your own thoughts, so you become afraid of your own anxieties.”

Hendricks suggests students practice replacing anxious thoughts with positive affirmations, including “restorying” past traumatic events. And Xiong asks his students to write down their negative thoughts, then actively question them.

“There’s always going to be a chance that you could make a mistake onstage,” says Xiong. “To challenge that would be to say, okay, what if that happened? Would my life fall apart? Often the answer is no. Just accept that it could happen, know that you can recover from it, and there is no reason to continue to linger on that mistake. This is creating a different pathway for them to go down, instead of spiraling into their negative thoughts. They can now question their thoughts.”

Reframe your experiences

Every performance should be regarded as just practice for the next, says Hendricks.

“Sometimes we think this is life or death,” she says. “Having watched students have juries, you can see the terror—like this is the only moment in their life. But it’s only one. They’re only practicing for the next jury.”

Recognize audience support

It’s important for students to understand that an audience is not there to judge a performance, but rather to simply enjoy it.

“People are here to listen to you play—not for your failure,” Xiong says.

Hendricks agrees: “For some reason, because we’ve made this thing where you perform on a stage and you have a proscenium between you and the audience, it becomes this practice of judgment that then brings fear with it. We need to change the culture.”