Category: Spring 2012

Going Digital

![]()

Find Esprit Online

A printed magazine is perfect for relaxing reading over breakfast or on the bus, while a digital magazine makes it easy to search for and share your favorite articles. Today’s readers expect their content to be available in both forms, and we know that CFA alumni are no exception. That’s why the College is now providing Esprit in hard copy and digital formats.

Beginning with this Spring 2012 issue, the articles in your print copy of Esprit are also available online, enhanced with additional links, photos, videos, and reader comments.

Photo by Michael Lutch

CFA Launches Virtual Concert Hall

By Amy Sutherland

When Melanie Burbules (’14) walked onto the stage of Symphony Hall last spring to perform in a BU production of Felix Mendelssohn’s Elijah, both of her parents were watching, despite the fact that her father was stationed in Baghdad and her mother was home in Chicago. Viewing the performance streamed live on their computers allowed the Burbuleses to share a simultaneous moment of parental pride.

Now, thanks to CFA’s new Virtual Concert Hall, more people can enjoy CFA events via virtual technology. The website now features several student performances and the 2010 Centennial Celebration of Roman Totenberg. More than 2,500 people have already watched the Elijah all the way through, more than double the number of people who attended the concert.

With the Virtual Concert Hall, BU joins a small but growing number of universities putting their concerts online, but no other school is yet recording in high definition or using as many cameras as CFA, says Casey Soward, School of Music assistant director of production and performance.

Dean Benjamín Juárez says the Virtual Concert Hall will increase the audience for CFA performances by making them more convenient and because they are free. “This is a fantastic way to share what we do in the school,” he says. “It’s an investment that’s impossible not to make.”

Juárez plans to grow the site incrementally, with several more concerts to be added next year. Over time, he says, the goal is to put more and more of the College’s 400 annual concerts online, as well as art exhibitions featured in CFA’s four galleries.

The latest addition to the Virtual Concert Hall: The BU Symphony Orchestra and Symphonic Chorus’s April 2 performance of Rachmaninoff’s The Bells and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11 was streamed live on the site and will be archived there.

This article was excerpted with permission from BU Today.

CFA Collage

Richard Crawley (Macduff) and John Irvin (Malcolm) with members of the BLO Chorus. Photo by Erik Jacobs for Boston Lyric Opera

Strengthening Ties with the BLO

On stage, in the pit, and behind the scenes, 30 members of the CFA community participated in Boston Lyric Opera’s season-opening production of Verdi’s Macbeth in early November. The cast featured Opera Institute graduate David Cushing (’04), current Opera Institute student John Irvin (’12), and Assistant Professor of Voice James Demler. CFA alumni, students, and faculty members also sang in the chorus, played with the orchestra (woodwinds, brass, and strings), and contributed to costume, lighting, and set design.

How did so many CFA affiliates end up on (or near) the BLO stage? Such high CFA participation, says Opera Institute Director Sharon Daniels, is a reflection of a longstanding informal relationship between the College and BLO and is also the result of a more formal collaboration recently begun under BLO’s new leadership. The partnership includes master classes for CFA students with BLO artistic staff, an opera arts course taught by BLO dramaturge John Conklin, and opportunities for CFA students and recent graduates to participate in BLO’s Emerging Artists program.

Beginning with its 2011–2012 season, BLO will help nurture young operatic talent by annually selecting nine Emerging Artists—seven singers and two coach/accompanists—to participate with the opera company onstage, in rehearsal, and at special events. Fully half of the singers chosen as Emerging Artists this season are alumni of the Opera Institute: soprano Meredith Hansen (’02), bass-baritone David Cushing (’04), and tenor John Irvin (’12). —Corinne Steinbrenner

In Memoriam

David Wheeler

Photo courtesy of American Repertory Theater

Associate Professor, School of Theatre, on January 4, 2012, at 86. Director and educator David Wheeler was a driving force in the Boston theatre scene. In 1963, he founded the legendary Theatre Company of Boston and served as its artistic director until 1975, working with a litany of now-famous actors, including Dustin Hoffman, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall, Spalding Gray, Stockard Channing, and Al Pacino, who has called Wheeler “one of the lights of my life.”

Wheeler later served as resident director at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge and directed successful productions for many other New England theatre companies. He also taught at several Boston-area universities, including Harvard, Brandeis, and BU, where he was an inspiring teacher of directing and dramatic literature from 1966 to 1979.

In a remembrance written for radio station WBUR, Boston theatre critic Ed Siegel (CAS’71) says audiences flocked to Wheeler’s productions for the “clarity, insight, and imagination that Wheeler brought to whatever he was directing—making the text come first and adapting the acting, set design, lighting, and everything else to serve those words.”

Wheeler, a veteran of World War II, is survived by his son, Lewis, and his wife, Bronia (CAS’47, GRS’48). The American Repertory Theater plans to host a public memorial service for Wheeler on Monday, May 14. —Corinne Steinbrenner

David Pressman

Photo by Michael Nelson

Former Chair, Department of Acting & Directing, School of Theatre, on August 29, 2011, at 97. A legendary television director, David Pressman made a lasting impact on the School of Theatre as founder of its acting and directing programs.

Born in 1913 in Tbilisi in what is now the Republic of Georgia, Pressman came to the United States at age 9. He began his career in the 1930s as a stage actor and director and then found success directing the new medium of television.

Pressman’s TV career came to a halt during the McCarthy era, when he was blacklisted for membership in the Communist Party. He was recruited to BU in 1954 by opera impresario Sarah Caldwell and served on the faculty of the then Division of Theatre Arts until 1959, leading the creation of the Department of Acting & Directing and forging important ties between the department and theatre professionals.

Pressman eventually returned to television, earning three Daytime Emmys during his 25 years as director of ABC’s One Life to Live.

A School of Theatre reunion honoring Pressman in 2004 was a standing-room-only affair, attended by such renowned actors as Verna Bloom (’59) and Olympia Dukakis (SAR’53, CFA’57, Hon.’00). —Corinne Steinbrenner

James V. “Tim” Nicholson

Photo by BU Photography

Professor Emeritus, School of Theatre, on August 9, 2011, at 84. Characterized as a team player and a talented theatre artist completely without ego, Tim Nicholson was held in great respect and affection by colleagues and students alike.

Nicholson came to BU in 1957, initially teaching lighting design, stagecraft, and theatre practice. In 1970, he assumed additional administrative duties, began teaching graduate directing, and became the primary advisor for all graduate students.

Even after his retirement in 1989, Nicholson continued to work on projects for the CFA community. Among them was the publication, Boston University College of Fine Arts, Reflections on the First 50 Years, 1954–2004, on which he collaborated with longtime colleagues William Lacey and Judith Flynn. In 2006, he made a generous gift to the College to refurbish the antique lighting fixtures in the Boston University Theatre.

“Tim was deeply devoted to the BU School of Theatre,” says Jim Petosa, director of the School. “His generosity was proof of his care, and his gentlemanly advice and expressions of support were always welcome to hear and receive. He will be greatly missed by our community.” —Ellen Carr

Jon Lipsky

Photo by Vernon Doucette

Professor, School of Theatre, on March 19, 2011, at 66. As a director, Jon Lipsky knew how to elicit the best from his actors. He believed that art lay hidden in the depths of one’s body, one’s soul, and one’s dreams.

“He did not force the work; he summoned it. Magically and reliably, he summoned it,” says Christopher Bannow (’09), who was among the thousands of students Lipsky inspired during his 28-year tenure as a playwriting and acting instructor at CFA.

Lipsky’s ability to translate emotions to the stage earned him critical acclaim. In 2007, he received the Elliot Norton Award for Best Direction for the plays Coming Up for Air (Alliger Arts) and King of the Jews (Boston Playwrights’ Theatre).

In the late 1970s, Lipsky became the in-house dramatist for Boston Theatre Works. During this time, he wrote Beginner’s Luck, They All Want to Play Hamlet, and A Matter of Ecstasy. His later plays include Maggie’s Riff, Molly Maguire, Book of Revelations, and The Survivor: A Cambodian Odyssey.

His book Dreaming Together: Explore Your Dreams by Acting Them Out was published in 2008. Dreams provided the basis for Lipsky’s full-length plays Dreaming with an AIDS Patient and The Wild Place. —Samantha Dubois

James Spruill (’75)

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

Associate Professor, School of Theatre, on December 31, 2010, at 73. Over the course of a five-decade career, James Spruill made his mark as an actor, a director, and a leader in the African American theatre community, but he is remembered foremost as an impassioned, dynamic educator.

“Jim Spruill was unfiltered, provocative, nurturing, challenging, and, most of all, devoted to his students and the art of teaching acting,” recalls Nina Tassler (’79), a BU trustee and president of CBS Entertainment.

Spruill came to Boston as an actor in the mid-1960s and, in 1968, cofounded the New African Company, which continues to mount the work of African American playwrights on stages across Boston, as well as in schools, colleges, prisons, and hospitals. He joined the CFA faculty in 1976 and taught acting, directing, theatre history, and literature until his retirement in 2006.

In addition to his stage performances, Spruill appeared on television and in several movies, among them the Steven Spielberg (Hon.’09) film Amistad. He also had roles in several films made by his son, Robert Patton-Spruill (CAS’92, COM’94), including Squeeze and Body Count. —John O’Rourke

Raphael Hillyer

The original Juilliard String Quartet (from left): Robert Mann, Robert Koff, Raphael Hillyer, Arthur Winograd. Photo by G. D. Hackett

Adjunct Professor, School of Music, on December 27, 2010, at 96. The founding violist of the Juilliard String Quartet, Raphael Hillyer taught viola lessons and chamber music studies at CFA from 1981 until December 6, 2010, just weeks before his death. A member of the Juilliard String Quartet for more than 20 years, Hillyer helped revitalize traditional chamber music, influencing and mentoring many younger quartets that followed.

Born in 1914 in Ithaca, New York, Hillyer began studying violin at age seven and joined the Boston Symphony Orchestra as a violinist in 1942. Four years later, he borrowed a viola and learned enough to successfully audition for the Juilliard String Quartet, which quickly gained acclaim for its innovative set lists.

After leaving the quartet in 1969, Hillyer began a teaching career that included posts at American University, Juilliard, Yale, Harvard, and BU.

Steven Ansell, principal viola of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and associate professor in the School of Music, told the Boston Globe that Hillyer “was a tremendous player, without a doubt one of the best violists of his generation.’’ —Samantha Dubois

A Greener CFA

For two years running, Boston University has been highlighted in the Princeton Review’s Guide to Green Colleges, thanks in part to the efforts at CFA.

A few years ago, a group of CFA staff initiated a recycling program for the building at 855 Comm. Ave., as well as for the College’s facilities across the street at 808. Now, every Friday at noon, students and staff for each floor collect blue bins full of paper, glass, and plastic, to be carted off by local recycling company Save That Stuff. Moreover, the Schools of Visual Arts and Theatre make it a point to reuse canvases, sets, and costumes, saving money as well as the environment. CFA buyers purchase greener paints and recycled or sustainable goods.

“We’re really on the move in terms of recycling,” says Liz Phillips, who spearheaded the initiative, called CFA Green. Phillips (MET’08) is the department administrator for the School of Theatre and managing director of the Boston Center for American Performance. “That’s true across the University. I like to think that CFA Green and a couple other groups started that in motion.”

Indeed, a year after the birth of CFA Green, Boston University formed a central Sustainability office to coordinate such efforts campus-wide. The recycling rate on the Charles River Campus shot up from 3 percent in 2006 to 24 percent in 2010. The Sustainability team credits this progress in part to the grassroots advocacy and efforts that bubbled up from the staff, students, and faculty at a few schools and colleges, such as CFA and the School of Education.

“We would be doing our students a disservice not to show them how to live a sustainable life,” says Phillips. “Even just doing the small things is really important.” —Patrick L. Kennedy

Artist at Work

![]()

James Fluhr (’11) • Actor, designer, and writer James Fluhr performed his one-man show, Our Lady, on the Huntington Theatre mainstage in October. The play, which honors the many gay teenagers who have turned to suicide in response to societal pressures, was the School of Theatre’s 2012 entry for the Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival, where it won honors in two categories: Distinguished Production of a New Play and Distinguished Performance by an Actor.

Photo by Kalman Zabarsky

Encore

![]()

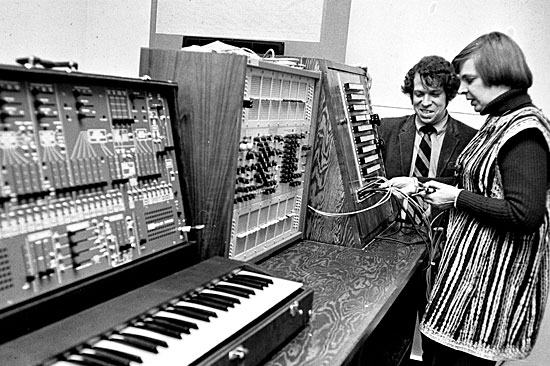

In the early 1970s, the Division of Music held its undergraduate course in electronic music in a lab outfitted with tape machines and a top-of-the- line ARP 2600 synthesizer. Today’s electronic music students work primarily on their laptops. Below (from left), graduate students Igor Iwanek and Heather Stebbins complete a sound check before an electronic music concert with assistance from Associate Professor Joshua Fineberg.

Photo by BU Photography

Photo by Vernon Doucette

Dressing Broadway

Tony Award–winning costume designer Jess Goldstein looks back on a career spanning English petticoats and Hollywood glam.

By Andrew Thurston; Sketches by Jess Goldstein

With well-placed stitches and carefully chosen swatches, Jess Goldstein (’72) ensures the stars on Broadway do more than act the part—he makes sure they look it, too. When it comes to costume design, Goldstein is A-list. He’s outfitted dozens of movies and smash Broadway shows, including the long-running Jersey Boys and the critically acclaimed 2011 Disney production, Newsies. A three-time Tony Award nominee (and winner for period comedy The Rivals), Goldstein has worked with such stars as Al Pacino, Kevin Kline, and Kristin Chenoweth. Here, he shares some of his favorite designs and the stories behind them.

Mrs. Malaprop, played by Dana Ivey, The Rivals, Lincoln Center Theater, New York City, 2005. Photo by Joan Marcus

1 ] Breeches to Bikinis • From petticoats to Speedos, sometimes in the same night; fortunately, not on the same stage. In 2005, Jess Goldstein was working on two very different plays: The Rivals, a comedy of manners written in the 1770s, and Good Vibrations, the Beach Boys musical. “I was constantly running between fittings of the glorious petticoats and breeches of late-eighteenth-century England,” says Goldstein, “to the wet suits and bikinis of an indeterminate period in Southern Californian culture. I even had to miss The Rivals’ opening night because of dress rehearsals on the other show.” Goldstein’s versatility would be rewarded: he scooped a Tony for his work on The Rivals.

Sir John Falstaff, played by Kevin Kline, Henry IV, Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, New York City, 2004. Photo by Paul Kolnik

2 ] Costume as Storytelling • A well-chosen costume can make the difference between an actor playing a character and becoming him. Despite decades of screen and stage success, Kevin Kline needed Goldstein’s help in 2004 to inhabit Falstaff, the bloated, errant knight of Shakespeare’s Henry IV plays. “Kevin was incredible as Falstaff,” says Goldstein, “but needed constant encouragement that he could make the physical transformation.” Goldstein adds that the production “really allowed me to show off the power of costume design as storytelling. The play shows a cross section of medieval life, from royalty to soldiers to peasants, and I felt I was particularly successful in making what is sometimes thought to be a rather primitive and clumsy period look attractive and sexy to modern eyes.”

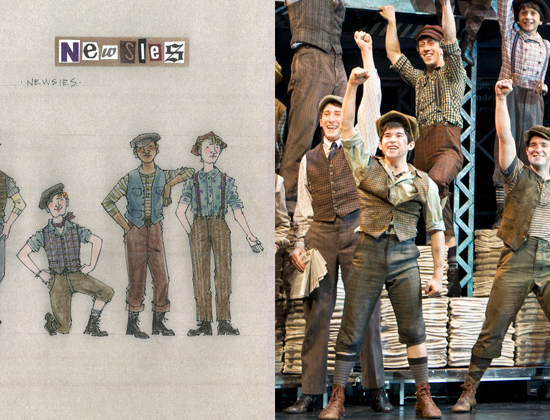

Newsies, Paper Mill Playhouse, Millburn, New Jersey, 2011. Photo by T. Charles Erickson, courtesy of the Paper Mill Playhouse

3 ] Extra! Extra! • A so-so movie in the 1990s, Newsies is proving a star performer on the contemporary stage. Goldstein suspects the Disney-backed musical, which tells of newsboys striking in 1899, could be in line for a long Broadway run. “I don’t think I’ve ever had as much fun on a show,” he says. “I didn’t really know what to expect of the young actors in fittings, but they all seemed to love their costumes and often remarked how much they wished people still dressed in those styles.”

Puck (bottom), played by Daniel Tamm, and Oberon, played by Bradley Whitford, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hartford Stage, Hartford, Connecticut, 1988. Photo by Jennifer W. Lester

4 ] Yuppie Shakespeare • This isn’t the cheeky Puck of history. For a 1988 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Goldstein was charged with spinning the sprite of Shakespeare’s forests into a character for a “postmodern yuppie world.” In the creative team’s vision of an industrial landscape, the mechanics—the gadgets that drive stage effects, such as putting winged characters into flight—also became part of the wardrobe. “The flying harnesses were difficult to conceal under the skimpy costumes, so they actually became a part of the look,” says Goldstein. “This is an early sketch of Puck that incorporates football pants, dunce cap, and a frankly theatrical hunchback pad.”

5 ] The Silver Screen • Sometimes stage leaps to screen and Goldstein’s designs follow—albeit with some tweaks. When comedic drama Love! Valour! Compassion! became a movie in the mid-1990s, Goldstein was asked to re-create and update his designs from an earlier Broadway production. In both adaptations, the all-male cast rehearses a ballet for an AIDS fundraiser: “The stage version did not allow the men the time offstage to make a full change into real ballet tutus,” says Goldstein. “They could only add tulle skirts and feathered headpieces to the white boxer shorts and tank tops of their previous costume. For the film, we went all out with the traditional classical ballet look. [I wonder if] the original concept wasn’t more interesting.”

Lotty, played by Jayne Atkinson, Enchanted April, Lyceum Theatre, New York City, 2003. Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Richards Associates

6 ] Tricky Twenties • Some eras are easier to re-create than others. The 1920s—the decade in which Enchanted April is set—is considered one of the most challenging, says Goldstein, with frills replaced by unappealing sharp edges. “I feel most historical periods need to be filtered somewhat for modern audiences who may not appreciate a need for museum-quality accuracy,” he says. “For Enchanted April, we tried to give the women’s boxy 1920s shape a little more curve and grace, and we used softer, lighter-weight fabrics for the men’s suits.”

Jersey Boys, August Wilson Theater, New York City, 2011. Photo by Joan Marcus

7 ] Big Man in Town • Wondering if you’ve ever seen a play outfitted by Jess Goldstein? There’s a good chance of it being this one. “Jersey Boys was that rare show that I knew was going to be an enormous hit just from reading the first draft of the original pre-Broadway production script,” says Goldstein. Of all the shows he’s worked on, Jersey Boys, now in its sixth year on Broadway, is one of the best known. Among Goldstein’s favorite Jersey Boys outfits are those worn by the show’s female actors. “There are only three women in the cast, but each plays about twelve different roles. This is my favorite set of their costumes, when they form the Angels to sing ‘My Boyfriend’s Back.’”

8 ] Rags to Riches • A quick-change conundrum: how to turn an actress from smudge-covered chimney sweep to a gold-glimmering star. “Quick changes can be tricky because when they’re really fast—under a minute—they inevitably lead to some sort of a compromise,” says Goldstein. “In The Apple Tree, Kristin [Chenoweth] had a matter of seconds to change from Ella the Manhattan chimney sweep to Passionella, the Monroe/Mansfield Hollywood star and icon; it meant really simplifying her makeup for both looks. Like a true Broadway star, Kristin was fearless!”

The Creative Life

Actor Julianne Moore and creative director Gael Towey talk about the arts, storytelling, and where they find inspiration.

Edited by Corinne Steinbrenner; Photo by Matthew Hranek

Their Manhattan homes are mere blocks apart, and they’re each mothers of two children. They both attended BU’s College of Fine Arts, and they share interests in storytelling, interior design, and healthy cooking.

When Academy Award–nominated actor Julianne Moore (’83) and Gael Towey (’75), the longtime creative director at Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia (MSLO), first met at a CFA alumni dinner, it was clear they had much in common—not least, their status as highly accomplished and multitalented women.

Moore—known for her intelligence, versatility, and distinctive red hair—has appeared in more than 50 films, ranging from the 1998 cult favorite The Big Lebowski to 2010’s critically acclaimed The Kids Are All Right. Her acting has earned her a Daytime Emmy, six Golden Globe nominations, and four Oscar nominations. In addition, her interior design talents have been featured in The World of Interiors magazine, and her popular Freckleface Strawberry children’s book series has inspired a successful off-Broadway musical.

After serving as design director for House & Garden magazine, Towey joined Martha Stewart Living in 1990 as its founding art director. She designed the magazine’s inaugural issue, establishing its iconic and award-winning visual style, and then moved into progressively larger roles at MSLO, directing the design of everything from magazines and books to home furnishings and merchandise. This year she accepted a new title as chief integration and creative director, overseeing the creation of digital magazines and mobile applications for the multimillion-dollar Martha Stewart brand.

The College of Fine Arts recently brought Moore and Towey together again—this time for an exclusive Esprit interview. Moore took a break from a busy schedule promoting the HBO movie Game Change, in which she portrays former Alaska governor Sarah Palin, for a casual conversation with Towey about arts education, raising children to be creative, and living a life in the arts.

Towey: You were an acting student at Boston University in the 1980s. Are there things you call upon that you learned at BU that are still important to you in your everyday life as an actress?

Moore: Absolutely. I had a variety of sources to draw from while I was there. Different techniques and methods were taught each year, and the one thing that I came away with is that there is no one method to acting, to performing. You have to find it yourself. You spend four years with some teachers you really respond to, and then there are other teachers whose methods you don’t respond to. At the end of the four years, you realize what you like and what works for you. So, absolutely, there are things that became fundamental to my acting.

Towey: Yes, it gave you a foundation. I was thinking about how, especially having children in college myself, so much of your education depends on what you bring to it as a student. I don’t know if all students realize the responsibility they carry when they go to university and how important it is for them to make choices and open themselves up to possibility.

Moore: I don’t think they do. I was at BU not long ago and spoke to some acting students. I talked to them about what was expected of them when they got out of school, but I think they should require those same things of themselves while they’re in school. I try to say it to my children even now. When my daughter says, ‘I don’t want to do this homework,’ I tell her, ‘Then don’t do it. Don’t do it and go in tomorrow and tell your teacher that you didn’t want to do it and didn’t finish it.’ Of course that makes her very upset, but I’m just trying to ask her to take responsibility. By the time you’re in college, you need to say, ‘I’m going to take responsibility for what I want to do and how I’m going to accomplish it.’

Towey: I think that’s true of visual artists, too. You have to open yourself up to take risks. Being willing to fail is important.

“It’s never a sure thing. As a musician, as a visual artist, as an actor—you have to be able to know you’re going to fail, and fail a lot.”

Moore: And you have to be brave about it. I talked to my daughter about this the other day, too, because she and her friends were all trying out for parts in a play. And one little girl said, ‘Well, you can’t get your hopes up because you might be disappointed.’ And I said, ‘No, you can get your hopes up. You should get your hopes up. You just have to be brave, because you might not get the part, and that’s going to be really disappointing, and it’s going to feel terrible. But you have to be brave enough to do it again, to try again.’ I think that’s what it’s about in the arts in general, because it’s never a sure thing. As a musician, as a visual artist, as an actor—you have to be able to know you’re going to fail, and fail a lot.

Towey: And it’s hard to find that inner resource. I think it actually takes a lot of practice. With your father in the military, you were brought up all over the world. You were in a new school almost every single year. Obviously, that had a big impact on how you approach life. I can imagine you felt as though you had to test those inner resources every time you walked into a new school and tried to make new friends.

Moore: I did, and the thing I learned is that behavior is not character. Behavior is mutable. I think that when you stay in the same place, you believe that behavior is a static thing, that it’s part of who you are. It’s not. It changes from place to place. What’s universal is a different sort of thing—it’s deeper. Universal truth—something that everybody shares regardless of language, culture, behavior—I’m always looking for that within a narrative.

Towey: Storytelling is such an important part of our lives. In the magazine business, that’s what we do, and that’s obviously what you’re doing, too.

Moore: And you’re doing it visually. That’s something that I tell acting students: look at the frame; don’t just hear the words. If someone has chosen to frame something a certain way and placed actors within it, there’s a narrative there. Or, there’s a narrative within a collection of objects in a room and the way they’re placed.

Towey: You’re a very visual person, so I wanted to ask you about the movie sets you’ve worked on. What are some of your favorite sets?

Moore: A Single Man comes to mind.

Towey: The house that your character, Charley, lived in was so 1960s, sophisticated.

Moore: The style was very Hollywood Regency, yes. And George, played by Colin Firth, lived in a really modern, tiny Lautner house that’s actually in Pasadena. It’s always great to be on a set where someone has taken a lot of care in the storytelling and put real thought into who your character is and what they would have around them and what would be meaningful to them. That’s just fun. It fills in your story.

Towey: I want to segue to the subject of raising kids. Giving my children the ability to learn how to be creative is a huge part of my life, and it’s made my life with my children and my husband so fulfilling. My husband is a designer, and we share a lot. You and your husband are both in the film business, and you obviously have a lot in common. What do you do to make sure that your children have that creative life?

Moore: I feel that exposure is everything. I made both of my kids take piano when they were five. My son took piano for a year, and then he wanted to take guitar. I said, ‘You can’t quit piano yet. At the end of the year, you can decide.’ Well he decided guitar, and he stuck with it. And now he’s a teen, and he’s been playing guitar all these years. My daughter struggled through piano, struggled through guitar; that’s not her thing. So with each child, you’re going to learn what sticks. In terms of visual arts, you try to demystify it by talking to them and bringing them to museums.

Towey: And it’s all here in New York. It’s the best place in the world to bring up children—what they’re exposed to just on the street is so inspiring.

Moore: Yes, you can see street artists and say, ‘Look at that. See what this person has done. What does it look like? How would you draw it?’ Even with the books that I write, when I talk to little kids about them, I tell them, ‘I wrote the words. Someone else did the pictures. I’m sure you make books in school. You can make them by yourself and put the words and pictures together, or you can get a partner like I have.’ You try to demystify it so that the book is not just something that’s created somewhere out there. It’s something they can understand.

Freckleface Strawberry series covers

Towey: I wanted to ask you about your writing. You’ve been able to intermingle your creative life as an actress with that of being a writer at the same time.

Moore: Well, I’m not a novelist!

Towey: I know, but you’re telling stories. And did the lessons in the stories come out of your own personal experiences?

Moore: I think for most children’s book writers, it’s all autobiography. I always tell little kids that everything they say about my character’s freckles in Freckleface Strawberry, people said to me as a kid. Freckleface Strawberry and the Dodgeball Bully is really about my experience hating dodgeball. Best Friends Forever, which is the third book, is a metaphor for marriage. So, yes, they’re all things I wanted to talk about, but they’re written from a child’s point of view.

Towey: How did you find the courage to try your hand at writing, to branch out from acting and try something new?

Moore: Well, it doesn’t hurt to try. That’s what my mother always said. You might as well try. The worst thing that can happen is that you fail. And it’s painful, and it will hurt your feelings—and my feelings have been hurt many, many times—but what else are you going to do?

Towey: Exactly. And for young artists who are just beginning their careers, would you recommend they concentrate on a single craft until they’re more experienced, or should they branch out from the beginning?

Moore: This is interesting because when I was at BU last year, a student asked me this. He said, ‘What should I do? Should I diversify?’ and I said, ‘We’re talking about your life. When you get out of school, you’re thinking about career, career, career. But take a step outside that and realize that your career is just one part of your life.’ Diversification is not about getting ahead; it’s about what you enjoy. So, by all means, do what you want to do. There’s no right or wrong.

“I think a creative life is a whole life. In a creative life you never stop working. You’re always looking. You’re always learning.”

Towey: I agree. It’s about passion. If you let your passion lead you, you’ll discover the wonderful things you can do. I think a creative life is a whole life. In a creative life you never stop working. You’re always looking. You’re always learning. Lifelong learning is one of the most important things you can do for yourself and the people around you.

Moore: I think that’s absolutely true.

Towey: And you have to learn so much. I was reading about your recent Sarah Palin movie and about the technical part of learning a character. It’s similar with art: craftsmanship is tremendously important. You begin with a creative inspiration, but it’s the time you spend on the execution—your technical craftsmanship—that enables you to fulfill the original vision.

Moore: I’m glad you brought that up. That’s something people don’t always talk about—about the things you have to do technically. It gives you a framework. If you have an idea, an inspiration, it can pull you around all over the place. Until you have a framework for it, it goes nowhere. That’s where your technique comes in: it allows you to take the idea and to shape it and present it. That framework is what school is all about. It’s what I learned from my teachers—different techniques and ways to structure things. You don’t exist as a creative person without that.

The Edge of Glory

After winning the opera world’s toughest talent competition, soprano Michelle Johnson is about to go global.

By Andrew Thurston; Photo by Paul Sirochman

As you’d expect from the soprano touted by the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Times as a future superstar, Michelle Johnson (’07) is listening to Verdi nonstop. Well, maybe a little gospel, too—she did grow up singing in a church, after all. And, sure, the Texan might occasionally blast a little Gaga from her car speakers.

“I’m on this kick,” confesses the winner of the 2011 Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. “I don’t know pop music at all, so I’m on a kick of learning it. My soon-to-be sister-in-law is a Lady Gaga fan, so she made me a list of songs to listen to.”

Johnson doesn’t have the playlist of an average soprano. As the Met judges confirmed, she doesn’t sound like one either.

“When you hear my voice, you’re able to tell it’s me and not Suzy from down the street,” says Johnson, who joins a select, stellar list—including stage legends like Renée Fleming and BU’s own Grace Bumbry (’55)—in winning at the prestigious Met auditions. “It’s richer, has a darker tone to it.”

It’s a big voice, too; a fulsome lyric soprano. In opera terms, that means she can compete with the booming sound of an orchestra, but still flutter gracefully between the high notes. Opera Institute Director Sharon Daniels enthuses like a sommelier when she describes Johnson’s voice as “beautiful, sizable, plummy,” but one that’s “quite rare and wonderful.” Daniels expects it to take Johnson “to the far corners of the Earth.”

As a kid, Johnson sang at church and in the odd school musical, but it wasn’t until eighth grade that she began to realize, “I have something special.” The toughest challenge for many sopranos is that even though they might have the beginnings of a remarkable instrument, their voices won’t likely fully mature until they hit their thirties. “You’re not going to be financially stable,” says Johnson, “until your instrument is stable.”

For years, Johnson posted herself as a mezzo-soprano—“I could get to the top notes, but I didn’t know if I really wanted to sustain up there”—until a music teacher “flat out said, ‘I won’t teach you anymore until you make the full switch’” to soprano. The change made, Johnson came to BU’s Opera Institute at just 22 (making her one of its youngest students) where she learned the craft—the languages, the stage presence, the daily drills—of being a working opera singer.

Now 29 and comfortable in her voice, Johnson really lets loose on stage. Track down an online video of Johnson performing and you’ll see, and hear, the refined energy: Johnson’s voice brimming with power, the singer keeping everything flowing evenly. If you snuck backstage, you’d see it in her preperformance routine, too: 20 minutes of quiet meditation and then, boom, “I’m off. I have to move.” Johnson says her brothers were all athletes growing up and her preparation sounds as if it’d probably be more at home in a locker room than a greenroom.

“You have to get pumped up, you have to psych yourself out in order to get the energy you need to go onstage.”

“You have to get pumped up, you have to psych yourself out in order to get the energy you need to go onstage,” she says. “But once I’m onstage, I feel at peace. I have to be comfortable, yet calculate and always be on my toes and thinking.”

Winning at the Met means that a lot more people will hear Johnson’s rich voice. “The biggest change,” adds Johnson, “has been that my name is on a radar now—and I have the most random people asking to be my friend on Facebook.”

If a little fame comes along, Johnson is happy to take it, but she’d mostly just love to make a living, and pay her parents back. Given her success at the Met, Johnson’s parents probably won’t have to wait too long for the repayments to begin.

From the Dean

The economy in our country and world has brought challenges to arts organizations. We tend, during times like these, to reduce ambitions and diminish dreams. Some think it’s safer to look to what we already know, and only to those people and ideas that are familiar. But I am happy to report that Boston University and the College of Fine Arts are not turning inward or scaling back our goals. We face the future as our students do—prepared and full of enthusiasm.

BU is poised to play a significant role in global arts education in the years ahead. BU’s history is replete with firsts: the first black dean at a predominantly white university; the first U.S. university to open all its programs to women; the first black female to earn an MD; the first U.S. university to offer a music degree. We innovated in the 19th century and continue to do so.

Embracing our roots means expanding efforts to find qualified students from underrepresented groups and redoubling our efforts to attract talented students from all areas of the globe. Excellence is our first commitment, but a global perspective, which is central to excellence, requires diversity in our faculty, students, disciplines, and programs. This broadens the educational experience for all by offering a view of the world as it is—richly diverse, challenging, and exciting.

To achieve these and many other goals, I ask for your help. Make a gift to the College, attend our events (either in person or through our ever-growing virtual channels), and submit regular class notes to keep us informed of your personal and professional progress. By supporting CFA, you ensure that the arts will continue to flourish not only at BU, but across the world. Your support directly benefits new musicians, actors, teachers, and artists who will enrich the lives of future generations around the world and remind us of what it is to be human.

Now, more than ever, the world needs the unvarnished truth that only artists and art can provide.

—Benjamín E. Juárez

Open Studio

By Corinne Steinbrenner; Photos by Kalman Zabarsky

Marc Schepens, a second-year student in the graduate painting program, makes large-scale paintings based on small shards of the past. Schepens grew up visiting his grandparents in Nahant, a community on a peninsula north of Boston, where he combed the beach for fragments of blue and white 18th-century Canton china that often wash up on shore there—remnants of shipwrecks from the colonial-era sea trade. Schepens now lives in Nahant himself and continues to collect the porcelain shards, which inspire his current work. He recently offered Esprit a tour of his painting studio.

In all graduate programs, you’re afforded some sort of studio space, but the spaces here are generous in size. The studios really encourage us to be here as much as possible and to generate as much work as possible.

In terms of painting surfaces, I’ve been using pages from books and medical journals—things we found in my grandparents’ attic after they passed away. These pages show images from the Wawel Cathedral in Poland, which I picked because I grew up Catholic, so there’s always a Catholic influence somewhere in the background inside of me.

There’s a little red up here in the corner. The painting started out mostly blue, but the color of my geraniums started to work its way onto the canvas.

I’m starting with something that is a very small piece of what was once a complete pattern, and then I’m amplifying it into a larger scale. Sometimes the images feel like things that are concrete and recognizable—like landscape or ocean. Other times they feel simply like gesture.

I’ve taken two contemporary art history courses with Greg Williams, and those classes have been invaluable. Art historians love to categorize periods—modernism, then postmodernism. It seems the term art historians are using to describe the world we’re in now is globalization. When I began working on paintings derived from these shards of china, I was struck that although we talk about globalization in terms of today and now, these shards are emblematic of globalization and cross-cultural exchange that have been going on for a long time.

When we did the studio lottery for this year, I specifically wanted to be on Commonwealth Avenue because I’d have the north-facing light, which is the best light during the day. I tend to work during the day because I have kids and try to get home in the evenings to be with them.

Keyword: Violence

What role does violence play in human society? What role can the arts play in the search for an answer?

By Corinne Steinbrenner; Photo by Graham Edmondson (’13)

Jack leads his band of war-painted hunters in a rhythmic dance. As more boys join the circle, their stomping and chanting become louder, more fervent. “Kill the beast. Cut his throat. Spill his blood. Kill the beast. Cut his throat. Spill his blood.”

We’re midway through act two of the School of Theatre’s adaptation of William Golding’s 1954 novel, Lord of the Flies, the tale of a group of British schoolboys who devolve into a tribe of savages after being marooned on a lonely island. The mood in the small black-box theatre is tense; even audience members who read Lord of the Flies in high school and know how the scene plays out are holding their breath.

By the time the boys disperse, they have, indeed, killed—not the unknown beast that haunts their dreams, but Simon, one of their own.

“The play really dropped in for us, as a group, when we got to the staging of Simon’s death,” says Jake McLean (’12), who acted the part of Jack, the ringleader. “We all stepped out of that first day thinking, ‘Wow. That’s scary.’ We felt what it would be like to participate in such an act.”

After being cast as Jack, McLean began talking with his professors about techniques for cooling down, “shaking it off,” at the end of a rehearsal or performance. “If you’re doing a comedy and it brings you joy, you want to carry that into your life,” he says. “I don’t want to carry around murderous, angry, twelve-year-old.”

Playing Jack, who transforms from head choirboy to head hunter, was “quite a journey,” says McLean, “and I began to realize that a lot of his transformation comes out of fear—fear of disapproval and fear of the unknown. One thing that we discussed a lot with Jack is that whenever there’s a problem, he doesn’t think logically how to solve it. He just goes, ‘Okay, we’re going to go out and kill something now.’ That’s how he copes with things, with violence.”

Lord of the Flies’ exploration of violence is the reason it was chosen as part of the School of Theatre’s 2011–2012 lineup. This academic year is the inaugural year of the College of Fine Arts’ “keyword initiative,” which encourages CFA’s three schools to center their annual programming on a specific word. This year’s keyword: violence.

Catalyst for Conversation

Dean Benjamín Juárez hopes that CFA’s annual keyword efforts will strengthen ties among CFA’s three schools and spark conversations across campus. “We are trying to build a two-way dialogue with schools and colleges throughout BU, inviting our community to feel, think, and act around themes that are relevant to all of us,” he says, explaining that CFA is including experts from throughout BU in roundtables and lectures associated with CFA performances and exhibitions.

It’s an idea that has succeeded on other U.S. campuses. Since 2006, the University of Southern California has sponsored a university-wide arts initiative called Visions and Voices that explores the university’s core values (“search for truth,” “respect for diversity,” etc.) through performances, film screenings, lectures, and workshops. In 2007, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill launched Carolina Creative Campus, a program that uses the arts to catalyze campus discussion around a specific topic. In its first year, UNC chose the theme “Criminal/Justice: The Death Penalty.”

Reed Colver, who helped organize the UNC program, says that first theme turned out to be far more relevant to UNC than anyone expected. Partway through the academic year—just before a planned performance of Dead Man Walking, a play about a convicted murderer awaiting execution—UNC’s student body president was murdered. Because of the sensitivity of its subject, Creative Campus organizers considered cancelling the play, but they ultimately decided, says Colver, “We need to continue to provide the space that we’ve been providing for dialogue about these issues.” The structured discussions held in conjunction with the performances, she says, “gave students, faculty, and staff a chance to talk through and process, within a fairly safe environment, what was happening in our day-to-day lives.” Creative Campus became a perfect example of art’s power to build community and to help explore and explain the human condition.

Choosing Violence

The idea of using violence as CFA’s first keyword came during a visit to the gym last winter. “I was on the elliptical machine at the Y,” says School of Theatre Director Jim Petosa, “and the news reports about the shooting of Representative Gabby Giffords came on the air. It was such a stunning moment.”

The extensive news coverage of Giffords’s attempted assassination prompted Petosa to choose violence as a theme for his School’s coming year of theatrical programming. When he shared the idea with Juárez, the dean was so enthusiastic that he proposed extending the theme across CFA. “And then it became this notion of a keyword, which is different from a theme,” says Petosa. “A keyword actually suggests a Google way of thinking—cloud-based thinking—which is a much more generous way of examining the potency of a given word.”

Petosa and colleagues chose a range of plays for the School of Theatre’s exploration of violence—from Monster (an adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) to Shakespeare’s bloody revenge story Titus Andronicus. Fittingly, considering the event that inspired this examination of violence, the School is staging two plays that deal with political assassinations: Execution of Justice, the story of Dan White, who assassinated San Francisco’s openly gay city supervisor, Harvey Milk, and Assassins, a Stephen Sondheim musical that explores U.S. history through the eyes of people who either assassinated or attempted to assassinate U.S. presidents.

For its keyword programming, the School of Visual Arts invited controversial painter Enrique Chagoya to give November’s Contemporary Perspectives Lecture (see sidebar). While on campus, Chagoya made a series of small prints for the School inspired by Francisco Goya’s famous series, The Disasters of War. Visual arts professors leading junior and senior seminars are also incorporating the theme of violence into their course discussions this year.

Because opera so often deals with the extremes of human behavior, Opera Institute Director Sharon Daniels had no trouble selecting violence-themed operas to include in her 2011–2012 season, including Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites, the story of 13 nuns sent to the guillotine during the French Revolution. BU Symphony Orchestra Conductor David Hoose also found he had plenty of material to choose from. “Unfortunately, violence is so omnipresent in our culture and our world,” he says, “that it’s something composers have responded to through a lot of music history.”

Hoose says that applying a keyword or other unifying concept to a season of programming is a wonderful idea that more arts organizations should consider. It’s particularly tricky, however, in a teaching environment. “The music that the orchestra plays or the chorus sings, that’s their curriculum,” he says, so while a keyword must be provocative enough to ignite conversation, it must also be broad enough to allow faculty to choose music, plays, and exhibits that will meet the educational needs of their students.

With these parameters in mind, CFA students and faculty members are already deep in discussion with professors and administrators from across BU, working to choose a fitting keyword for next year’s explorations.