Category: Features

Objects of Her Affection

Anna Valdez layers personal stories into lush, plant-filled paintings

By Andrew Thurston | Photos by Shaun Roberts

Artist Anna Valdez’s California studio is full of plants. Vines tumble from shelves stacked with art books, and succulent green leaves frame oversized canvases. Her childhood home bloomed with flora, too: her dad grew up on a farm and worked in a nursery.

Self-Portrait in Studio (2019) Oil and acrylic on canvas 72 x 72 in. In this piece, Valdez has obscured her face behind a fiddle-leaf fig plant.

“Plants remind me of home and they just bring life to a space,” says Valdez (’13). “And they provide form in my paintings. They grow into the space and create lines. They really help me in navigating my compositions.”

Plants are everywhere in Valdez’s recent creations: in 2019’s Self-Portrait in Studio, the artist’s face is hidden by fiddle-leaf figs; 2018’s Landscape in Studio is a painting of a painting of palms, snake plants, and more.

Valdez’s work—primarily oil on canvas, but also monotypes, ceramics, and wallpaper—has been shown at galleries and museums across the United States and Canada. In 2018, Facebook commissioned her to paint a mural in one of its Menlo Park, Calif., buildings.

In its review of her 2019 New York exhibition Natural Curiosity, art and culture magazine Juxtapoz complimented Valdez’s “signature palette of rich reds, bright yellows and sumptuous surfaces,” calling the show “visual poetry at work, at once rooted in art-historical practices while also remaining faithful to the present moment.” Vice has said her “houseplant paintings have seriously chill vibes.”

These items in Valdez’s studio make appearances in paintings such as Objects of Affection (below, right).

Valdez has painted sparse deserts, rocky bays, even old beer cans, but for the past couple of years, her botanical studio has been the star of her work. It’s not just crowded with plants. The space is filled with canvases and painting supplies, books, fabric wall hangings (her mom is a quilter), sculptures, pottery, shells, an upturned milk crate.

“The paintings I’m making right now are very much about the studio,” she says. “It’s an environment that I have complete control over and have curated over time. I suppose I end up loving the space that I am creating as it becomes reflective of a personal landscape or as a self-portrait.”

In 2020’s Objects of Affection, the canvas brims with details from Valdez’s studio. A skull, a Venus de Milo statue, and an amphora of the goddess Diana fight for space on the desk; a cow pelvis leans against a stack of books about women artists. There’s a story in the objects—all what she calls symbols in art history.

“I wanted to make a painting that glorified women in art, but without it being a nude of a woman reclining,” she says. “When you see women depicted in art, it’s usually from a male lens, so it’s usually sexualized.”

Objects of Affection (2020) Oil on canvas, 85 x 80 in. The painting brims with details from Valdez’s studio.

Objects of Affection is a big painting, more than seven feet tall and six feet wide. Valdez says she spent a lot of time climbing up and down a ladder to add the many details.

“It’s a very physical action to make that painting,” she says. “It’s interesting because big paintings are considered masculine paintings. I like that little bit of duality in the piece.”

Valdez appears in few of her paintings, but says they’re all “self-portraits to some degree.” Before becoming an artist, she studied anthropology and archaeology and sees parallels between recording the past and chronicling her present.

Objects of Affection, solo exhibition installation at Hashimoto Contemporary in San Fancisco, Calif.

“When I was studying archaeology, we would re-create and reconstruct someone’s life based off the objects that were in that space,” she says. “You would write a story from the things they surrounded themselves with.”

Despite her autobiographical approach to art, Valdez’s paintings are not straightforward retellings of her life. The paintings show not only what she sees in the studio, but what’s on her mind—things she’s noticed and thought about over days and weeks.

“There are so many moments that go into making one painting,” she says. “I try to layer a lot of moments into a piece. You see me as a person in it.”

Boston View with Taxidermy Butterflies (2019) Oil and acrylic on canvas 52 x 42 in. In some of Valdez’s paintings, the view shown from a window may be an artistic lie: a snapshot from a previous day or even of a different place altogether.

Occasionally, the view shown from a window may be an artistic lie: a snapshot from a previous day or even of a different place altogether. Sometimes, the artworks shown hanging on her studio walls live only in Valdez’s sketchbook—they have no canvas of their own.

“And there are little surprises that happen,” says Valdez. If she paints a vase into a picture that doesn’t exist beyond the canvas, she’ll try to re-create the vase in real life—then paint it, for real this time, into another work. “I like to play,” she says. “I like to not take myself too seriously.” When galleries show her work, viewers can track the genesis of an object: the painting that gave birth to its fictional creation, the ceramic that made it real, the painting that immortalized it.

“I am fascinated by how one idea can lead into the next,” says Valdez. “Or, more specifically, how one painting creates an idea for the next painting. Incorporating ceramics and other mediums into my still life installations feels like a natural step.”

Landscape in Studio (2018) Oil and acrylic on canvas 66 x 84 in. Most of Valdez’s paintings start with a rough ballpoint pen sketch. Then she’ll do an underpainting in acrylic before building the final piece with oil paints.

Most of Valdez’s paintings start with a rough ballpoint pen sketch—she carries a sketchbook everywhere. Once she’s set up her canvas, she’ll do an underpainting in acrylic—“just getting the skeleton of the painting down”—then begins building the final piece with oil paints. The paints are homemade: she buys pigments, mixing them with oils in her studio. It’s a practice she picked up during Associate Professor Richard Raiselis’ CFA classes on painting and color.

“It’s this journey of this relationship to making the whole painting,” says Valdez, who compares it to growing, making, and fermenting her own food. “It gives me a better understanding of why certain colors will work with each other, understanding the chemistry of why one pigment is oilier than another, its absorption rate, its lightfastness, how it will change over time.”

Anna Valdez (’13) has filled her California studio with plants. “Plants remind me of home and they just bring life to a space,” she says.

Reviewers often comment on Valdez’s use of color, praising its Californian brightness or making favorable comparisons to Henri Matisse. But her relationship to the vibrant colors in her work is complicated. It’s one reason she doesn’t expect the COVID-19 pandemic to reshape what or how she paints.

“I’ve struggled with depression and anxiety for most of my adult life,” she says. “People will look at my paintings and they’ll assume I’m a really happy person. These things are ways of focusing my energy and being able to step into this reality that I’m creating. I don’t want to change that, because I find safety in these spaces I’m creating.”

The Future of Opera

Chicago Opera Theater Music Director Lidiya Yankovskaya is one of America’s few women conductors and a force for change

By Andrew Thurston | Photo by Karen Almond

If you watch any US orchestra, particularly one with a multimillion-dollar budget, you’re almost guaranteed to see a white man standing on the conductor’s podium. Most estimates put the share of women conductors in America at or below 10 percent—and that’s only if you include those holding the baton for community groups, youth orchestras, and summer festivals.

At Chicago Opera Theater, Lidiya Yankovskaya is among the few to crack an especially thick glass ceiling. She’s one of only a handful of women conducting at a leading US orchestra—and one of just two at a major opera company.

“There’s a larger percentage of women who are studying conducting at universities, conducting with smaller organizations, or doing really fantastic work out there,” says Yankovskaya (’10), who sets the tempo and cues in the musicians as Chicago Opera Theater’s Orli & Bill Staley Music Director. “Not enough of them have gotten opportunities to move to the next level and work with larger-budget institutions. But I think it’s changing and will probably continue to change.”

In part, that change is a result of Yankovskaya’s efforts. She chooses work that lifts young composers and helps mentor women looking to follow in her path.

"Her presence behind the podium is breaking down barriers that have long existed for women in the industry.”

“Her presence behind the podium is breaking down barriers that have long existed for women in the industry,” says Ishan Johnson, associate director of development at Chicago Opera Theater. A voice performance major at CFA, Johnson (’06) has known Yankovskaya since 2008, when the two worked on an Opera Boston performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose. “There is a lack of minority and women leadership in opera administration, and Lidiya seeks to change that.”

A Nontraditional Trajectory

Born in perestroika-era St. Petersburg, Yankovskaya spent her early childhood in a crumbling Soviet Union, then in a Russia struggling to find its identity. As the country staggered through coups and constitutional crises, waves of Jewish families left, including Yankovskaya’s. In 1995, they fled their home in Russia and became refugees.

“I remember passing by a major square in the middle of the city where fascists would fly large swastika flags and hand out pamphlets that said ‘Kill all the Jews’ on them,” she told Newsweek in 2016. “Russia, in general, at the time was in economic and political turmoil, so there was a lot of hardship overall. When that happens, people tend to blame any larger minorities that exist.”

Many Russian Jews emigrated to Israel, but the Yankovskayas came to upstate New York. Despite the upheaval for young Lidiya—just nine when her family moved across the world—there remained one constant: music.

As a child, Yankovskaya studied piano and voice, adding violin when she moved to the United States. Music was more than a hobby. “It was always something I lived for and that was a top priority for me. I even remember as a kid saying I’d rather just stay home and practice than go do the social thing.”

During high school and college—she studied music and philosophy at Vassar College—Yankovskaya kept practicing and playing, but wasn’t sure what a life in music would look like.

“You see these traditional musical trajectories of where your career would be,” she says. “For me, it seemed that solo piano would be the thing I would have to do, and I did not want to sit alone in a practice room for that many hours and be traveling alone. That just wasn’t right for me.”

Her undergraduate experience included conducting—and she’d even had a few turns with the baton as a teenager. But it was “not something I realized you could make a career out of,” says Yankovskaya.

At CFA, her thinking began to change. For two years, Yankovskaya studied musicology, music theory, and conducting techniques, learning the technical skills necessary to hold an orchestra together. She also began to work as a conductor, standing out front for Opera Boston, Boston Opera Collaborative, and Lowell House Opera. After graduation, she was appointed artistic director and conductor for the Juventas New Music Ensemble, a group dedicated to performing the work of young, contemporary composers, and later added the Commonwealth Lyric Theater to her résumé. Soon, she was being hailed as a rising star.

“If there were a futures market for classical music, the touts would be pushing Lidiya Yankovskaya,” wrote Keith Powers for WBUR in March 2017. “She’s busy. She’s busy because she’s good.”

Three months after that glowing review, Yankovskaya was named music director at Chicago Opera Theater.

“She is as skilled with operas of the past as she is with works of living composers,” said the president of Chicago Opera Theater’s board of directors, Susan J. Irion, of the appointment. “Lidiya is sure to be a charismatic ambassador of opera in today’s world.”

New Audiences

There’s a common conductor stereotype: tyrannical, wild-eyed, eccentric. It’s generally unfair—and it’s definitely not Yankovskaya. She describes conducting as a collaborative process, working with individual musicians to help them become part of a whole. Sometimes, that simply requires her to provide a channel for them to connect with each other; other times, she has to firmly guide them. She says each group of musicians and each piece of music bring their own dynamic—it’s as much an exercise in psychology as understanding and interpreting a score.

“One type of artistic work may require something very rigid and precise, while another needs complete freedom,” she says. “One of the things I strive for is figuring out for each piece of art, what does this piece need from me in this moment, what do I need to do to create the greatest impact?”

There’s also plenty that happens offstage and outside of rehearsals. Yankovskaya is a leader and figurehead for Chicago Opera Theater, working with donors and shaping the organization’s direction through its choice of shows. Given her history, Yankovskaya is especially interested in Russian masterpieces, but she’s also an advocate for contemporary opera. Under her leadership, the theater has given Chicago premieres to work as diverse as Jake Heggie’s 2010 opera, Moby-Dick, and Tchaikovsky’s 1892 lyric opera, Iolanta.

As music director of the Chicago Opera Theater, Lidiya Yankovskaya ('10) makes it a point to choose work that lifts young composers and helps mentor women looking to follow in her path. Photo by Kate Lemmon

"One of the things we focus on is bringing work to the stage that speaks to our audiences today and that is about issues or questions that may arise for our audience."

“One of the things we focus on is bringing work to the stage that speaks to our audiences today and that is about issues or questions that may arise for our audience,” says Yankovskaya. “Even if it’s for traditional work, making sure that we connect it to our audiences and their experience.”

One part of that is helping the theater reach new audiences. In February 2020, the theater premiered Dan Shore’s Freedom Ride, about the civil rights activists who rode buses to protest segregation. The show was produced in partnership with the Chicago Sinfonietta, which aims to improve diversity in—and increase access to—classical music.

“She’s made a commitment helping to make opera accessible to different communities,” says Johnson, “exploring repertoire that adds to the canon, and finding innovative ways to bring opera to a greater audience.”

Yankovskaya also started Chicago Opera Theater’s Vanguard Initiative, a mentorship and development residency program for emerging opera composers. And, as music director, she’s involved in the theater’s broader educational efforts, including one in Chicago Public Schools that gives children the chance to write their own operas.

Just before she spoke with CFA, Yankovskaya was on a call in support of the Taki Concordia Conducting Fellowship, which mentors young women hoping to make it at the highest level. In 2015, she was one of those who benefited from its backing.

“One of the most important things in order for any industry—for our world—to have progress and change moving forward is to attract the brightest young talents,” says Yankovskaya. “It’s also important to make sure that we fight the inequities that exist that prevent new ideas from entering our work.”

A Refugee Orchestra

As a refugee, Yankovskaya is also focused on tackling the inequities that impact people forced to flee their home countries.

In 2016, she founded the Refugee Orchestra Project to help raise awareness of the role émigrés play in American society. The orchestra, which has played concerts across the northeastern United States and in the United Kingdom, brings together musicians who found shelter in the US after escaping persecution, as well as their families and friends. Yankovskaya says the nonprofit proved especially vital during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Because so many refugees lack family networks or other support systems, they’re especially vulnerable to health or economic insecurities.

Yankovskaya founded the Refugee Orchestra Project in 2016 to raise awareness of the role émigrés play in American society. Photo by Scott Bump

“We commissioned composers to write solo work for some of our performers that they can play on their own, record on their own,” she says. “It was an opportunity for the creation of new work and to showcase the artists and composers we work with—and to give them some employment and some opportunity to create.”

With theaters shuttered for much of 2020, Yankovskaya has experimented with other virtual projects, too, including digital performances and online conversations about the inner workings of an opera theater. While that may have encouraged an exploration of different ways of reaching new audiences or sharing music, she says the year has mostly been a chance to reflect on what she loves the most.

“To me, live performance is irreplaceable,” she says. “I so miss being in a room with people making music. I do not think there’s a substitute for that.”

Also in This Issue: How CFA professor Michael Reynolds supports youth music education programs.

Mining the Past, Mirroring the Present

Adrienne Elise Tarver’s art explores perceptions of Black women

By Taylor Mendoza | Photos by Stephanie Eley

In Adrienne Elise Tarver’s Three Graces, a trio of women stand together in naked repose. Surrounded by sugarcane and banana and pineapple trees, they lean into each other: hands gripping hands, arms and heads resting on shoulders. It’s a seemingly peaceful scene—but the inspiration for the painting is mired in racism. Three Graces is based on a photo Tarver (’07) found online showing Black women who were exhibited in Europe in the 19th or early 20th century. In Tarver’s painting, the women’s expressions are solemn and shadows of palm fronds slash across their shoulders and faces, reminiscent of the bars of a cage; the foliage covers turquoise boxy forms, suggesting a constructed background.

Three Graces (2019) Oil on canvas 84 x 72 in. The painting is based on a photo Tarver found online showing Black women who were exhibited in Europe in the 19th or early 20th century. Adrienne Tarver

“There were human zoos all around Europe and America throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries,” says Tarver, an interdisciplinary artist whose work has been shown across the world and lauded by publications like the New York Times and Brooklyn Magazine. “We understand how wrong that situation is and how exploitative it is, and yet the way the women were posed, it reminded me of so many images I had seen through my entire education, which had been sculpted and painted by mostly European men.”

Tarver was particularly reminded of postimpressionist Paul Gauguin’s exoticized and idealized depictions of French Polynesia and the women who lived there. She says the trope of the sexualized tropical seductress is one that has influenced the perception of modern Black women and that she has explored in much of her art.

“My work for the past five years has really been about Black female identity within the Western landscape,” she says. For Tarver, Black femininity of the past and present are inseparable. “I was thinking about the dualities of how we have been made to exist within this context, from this domestic, silenced figure who’s supposed to fade into the background to this oversexualized tropical seductress on display, and figuring out the narrative to give women in these spaces more agency.”

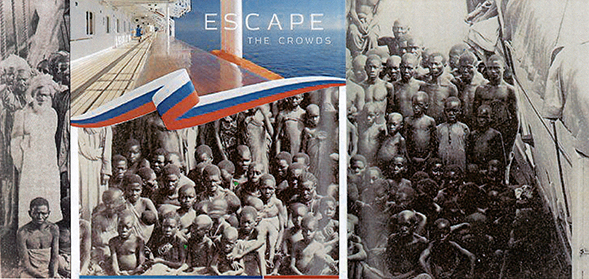

Escape

Three Graces debuted in January 2020 in Escape, an exhibition of Tarver’s work at Victori + Mo, a contemporary art gallery in New York City. The exhibit showed how the history of colonialism continues to impact Black women, showing lush tropical landscapes, vacation photos, and cruise ads, as well as images of human suffering and exploitation.

Escape the Crowds (2019) Cut paper collage. In collages like this one, Tarver subverts imagery from the tourism industry, calling attention to its roots in slavery and colonialism. Adrienne Tarver

“I was thinking about the duality of the word ‘escape,’” says Tarver, who centered the exhibition on the tourism industry and its roots in slavery and colonialism. “Sandals resorts and all of these vacation places, they all use ‘escape’ in their ads. The idea that you’re escaping your normal life, you get to go visit this place for a moment and forget everything. It just felt so ironic, because, ultimately, these places were built upon slave labor. The people who were creating these seductive landscapes that everyone is trying to escape to would have loved to escape to freedom.”

Escape also included a projected installation of tropical vacation photographs from the ’60s and ’70s. Tarver says she wanted to play with the feelings of nostalgia the photos provoked.

“It’s easy to fall into the warm, fuzzy feeling of memory with that, and as you walk down this narrow hallway, there are these collages juxtaposing ads for cruise ships and resorts with historical imagery of plantation workers, domestic help, and slave ships, so it’s clear that this more lighthearted thing is not as it seems.”

Head Above Water (2018) Oil on canvas 84 x 72 in. New York Times art critic Jillian Steinhauer wrote that the painting first connoted “glamorous freedom,” but after seeing works like Three Graces, “instead of seeing a scene of luxury, I imagined one of the women swimming to freedom.” Adrienne Tarver

The first painting viewers saw as they entered Escape was Head Above Water, which shows a woman’s legs dangling as she floats in sunlit water. Her crisp white bathing suit bottom contrasts with her brown legs. In her review of the show, New York Times art critic Jillian Steinhauer said when she first saw the painting, it suggested “glamorous freedom,” but after seeing the slideshow and works like Three Graces, “instead of seeing a scene of luxury, I imagined one of the women swimming to freedom.”

Art and Identity

Photography has long been an important part of Tarver’s art. While Three Graces was influenced by a photograph she found online, much of her earlier work was inspired by family photos—in particular those of her older brother. He died when she was 16.

“I painted a lot of photos of him, of him and me, of my family,” she says. “I went to a summer program at the Art Institute of Chicago and made this series of 16 small paintings all arranged together of different parts of my brother’s life.”

Tarver teaches at the Savannah College of Art and Design's Atlanta campus, where she is the associate chair of fine arts.

Although Tarver had initially thought of architectural design as a potential outlet for her creativity, her brother’s death prompted a fresh look at her plans. “I was really understanding how short life is,” she says. “I really don’t know if I would have pursued art if that hadn’t have happened.”

“It’s not possible to separate my experience as a Black woman from my art, because so much of my art is about my experience.”

At CFA, Tarver shifted away from portraits of her family—“I couldn’t separate how people talked about the art from what I felt about my family”—and began to use her art to explore what it meant to be Black and female in America.

“I got a bunch of old silver platters and silver serving things and I started doing a lot of self-portraits. I balanced the tray on my head with the objects, taking on this character of a house servant. I was diving into this history of who I was to America—the domestic woman.”

Now an associate chair of fine arts at Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, Ga., Tarver says her identity as a Black woman continues to be essential to her work. “It’s not possible to separate my experience as a Black woman from my art,” she says, “because so much of my art is about my experience.”

Projecting Futures

Escape closed on March 14, 2020, around when New York placed coronavirus-related restrictions on its residents. While Tarver had some downtime in the wake of her exhibit closing, the uncertainty of coronavirus and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests have inspired her to explore the ideas present in the exhibition, as well as what the future means to Black people.

“The longer we were in this situation, the more unknown it became, I thought a lot about fortune-telling and tarot,” says Tarver, who began studying the stories of—and attitudes toward—Black women like famed New Orleans Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau and TV psychic Miss Cleo. “There’s this idea of the Black woman holding some sort of deep wisdom or mythology, so there’s always a separation between this world and their world. In a moment where there’s so much uncertainty, I think people fall back to religion or astrology, just because nobody else can tell them real answers.”

This summer, Tarver started making her own tarot cards. Using ink, oil pastel, and colored pencil, she created a series of vibrantly colored images inspired by Afrofuturist ideas and imagery of the tropics. The titles of the works share the names of cards typically found in a tarot deck, such as High Priestess and Chariot. In Strength, a woman sits perched on an elephant’s trunk. Both woman and elephant are painted in washy ink, starkly contrasting with the bold yellow sky behind them and the bright blue ground beneath them, which is thickly built up with pastel. Tarver will eventually make these images into a printed deck of cards.

“It was this understanding that saying that we exist in the future—that there’s a future for Black people—is actually a radical statement,” says Tarver. “This idea of projecting futures, of telling fortunes, is a radical idea in and of itself, and telling somebody that you will exist tomorrow is a really heavy statement when you are consumed with how unpredictable life can be.”

Changing Minds

Good cop, bad cop, superhero. Michael Chiklis discusses how he reinvented himself to stay on top in a fickle business and dishes on his new show, Coyote

By Mara Sassoon | Photo by Patrick Strattner

Michael Chiklis

(’85) earned critical acclaim for his role on The Shield, for which he won a 2002 Emmy and a 2003 Golden Globe. Reed Saxon/AP (top); Kevork Djansezian/AP (bottom)

In the 2002 pilot episode of the hit FX series The Shield, the show’s merciless and corrupt protagonist, Los Angeles Police Department detective Vic Mackey, played by Michael Chiklis, brutally beats a suspect and murders a fellow officer in cold blood—and it only gets worse from there. For the rest of the show’s seven seasons, Mackey displays increasingly disturbing and illegal behavior: torturing and killing suspects, stealing evidence, embezzling money. Not only did the events of that first episode make it onto Rolling Stone’s “The Shocking 16: TV’s Most Heart-stopping Moments,” but Entertainment Weekly also named Mackey one of its “16 Ultimate TV Antiheroes.”

It’s a role Chiklis (’85) played with compelling, can’t-look-away grit and one that earned him critical acclaim—he won a 2002 Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series and a 2003 Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Television Series Drama. And he’s bringing a similar captivating performance to his starring role in the upcoming series Coyote. But before he got to the A-list, Chiklis had plenty of time out of the limelight, working in a host of small theaters, waiting a lot of tables, and even starring in a movie so controversial he thought he’d never act again.

The Acting Bug

“My parents used to tell me that I announced when I was five years old that I was going to be an actor,” Chiklis says. Growing up in Andover, Mass., he recalls watching The ABC Comedy Hour, which featured a group of comedic impressionists called The Kopykats that included the actors Frank Gorshin and Rich Little. Chiklis would walk around “imitating those two guys imitating other people” and make people laugh. “I think it was that response that made me feel like acting was my calling.”

That calling became a little more real during the ninth grade, when Chiklis starred as Hawkeye Pierce in his school’s stage production of M*A*S*H. “It was pretty racy for a high school play,” he says. His turn as the chief surgeon caught the attention of a casting director from a local summer stock theater, landing him a spot in a production of Bye Bye Birdie. The production’s director, Mark Kaufman, would become Chiklis’ first theatrical mentor. When Kaufman cofounded the Merrimack Repertory Theatre in Lowell, he cast Chiklis in a production of Romeo and Juliet during its first season.

“I gained incredible insight from watching Mark open a regional theater, from inception to fruition,” Chiklis says. “Seeing that process and getting to be onstage so much, it solidified my love for the theater and acting.” Kaufman also encouraged him to apply to Boston University’s theater program. It was the only school Chiklis applied to. “Now, I think to myself, ‘Oh my God, what if I didn’t get in?’ I don’t know what I was thinking.”

Chiklis at a rehearsal for a 1984 BU mainstage production of The Hostage. Rehearsals, he says, “were where I learned the most.” BU Photography

Chiklis attributes much of his success to the guidance he had as a young actor from people like Kaufman and—at CFA—the late Jim Spruill, who was an associate professor of theater. “Good mentorship can completely change the outcome in a person’s life,” Chiklis says. That kind of mentorship, he believes, extends far beyond acting advice. During his freshman year, he was blindsided by the news that his parents were divorcing. “My family broke. It really cracked my foundation and sent me into a kind of a spiral.” His grades and performances started to suffer and Spruill took notice. “He knew I was a good student, that I loved the craft. But all of a sudden, I was aimless and unfocused. He cared enough to say, ‘What’s up with you? What’s happening?’ He nurtured me through it. He cared enough to just ask a couple of questions.”

While Chiklis fondly recalls performing in shows like On the Razzle at the Huntington Theatre Company, which BU had established during his freshman year, he loved the rehearsals more than anything. “They were where I learned the most. At rehearsals, we were exchanging ideas—students from all over the country, from every race, creed, and walk of life. The truth is, we would go at it. Everyone was super opinionated and we discussed and argued about the shows.

“BU just opened my mind to so many things, so many people. It made me think, ‘Wow, there’s just so much to know.’”

Breaking Through

As graduation loomed, Chiklis envisioned himself heading to New York and getting a big break on Broadway. He moved to the city two days after graduating, ready to make headlines.

“I commend the School of Theatre for all the things I learned in terms of the craft and how to be the best actor that I could be. But what was lacking at the time was learning the vocational side of it—the business of show business,” he says. “That’s why I love coming back to BU and speaking to students, because I feel like I was that wide-eyed kid five minutes ago thinking, ‘Please give me some insight.’”

Chiklis spoke at the 2018 CFA Convocation. “Music, art, theater, dance, film, all of these art forms make the world a far better place,” he told the graduates. “Can you imagine our world without them?” Video by BU Productions

“I love coming back to BU and speaking to students, because I feel like I was that wide-eyed kid five minutes ago thinking, ‘Please give me some insight.’”

When Chiklis arrived in New York, Broadway was in a slump. “There were only maybe eight theaters lit,” he says. “It was all musicals and they were mostly revivals. There were almost no original musicals happening at that time.” He found some small off-Broadway and off-off-Broadway gigs, and did a few performances at La MaMa, the experimental theater group in the East Village. But he was mostly biding his time, waiting tables and bartending to make a living, and hoping that something big would come along soon. It would take two years.

Chiklis was working as a waiter at a West Village restaurant called Formerly Joe’s, alongside the late chef Anthony Bourdain and an up-and-coming Edie Falco. One day, his agent called the restaurant’s phone—Falco was the one who picked up: Chiklis had gotten a break. While he was still at BU, a casting director for a forthcoming film adaptation of Bob Woodward’s John Belushi biography Wired had spotted Chiklis in the senior theater showcase in New York City at Lincoln Center and offered him an audition for the role of Belushi. It took more than 12 auditions over the course of two years to finally get the role.

Things were looking up.

Reinvention

Until they weren’t.

Woodward’s book had reaped its fair share of controversy when it was released, with Belushi’s friend and Saturday Night Live costar Dan Aykroyd claiming it misquoted him and misrepresented Belushi. When the film adaptation was announced, there were plenty of vocal opponents: Chiklis has long maintained that at least one of them warned casting directors not to hire anyone from the movie. Wired’s coproducer Edward Feldman told Time magazine months before the film was released that “word was put out that this was a project not to be touched.”

“Here it is, I got a huge break playing an icon in a big feature film with an Academy Award–winning producer. It was a completely exciting, life-changing moment,” says Chiklis. “And then, by the time I’m not even finished filming the movie, I find out that I’m going to be blacklisted from making movies. My career seemed like it was over.”

For a little more than a year, Chiklis says, he was snubbed: “I couldn’t get seen for anything,” he says. “It was a horrible, fretful time.”

When the film eventually appeared on screens, Chiklis says it was “cut to pieces to avoid the onslaught of lawsuits pending against it.” The movie was panned. Moviegoers walked out of the 1989 Cannes Film Festival premiere.

"I did what I had to do to change minds,” Chiklis says. “It’s a very fickle industry. Listen to the lyrics of Frank Sinatra’s song ‘That’s Life’: ‘Riding high in April, shot down in May.’ That is exactly the life of an actor.” Patrick Strattner

Chiklis returned to New York and played some small parts in stage productions while trying out for guest roles in popular television series. Finally, the television doors opened when the late Burt Reynolds advocated for him to get a part in an episode of his show B.L. Stryker. A cameraman who had worked on Wired was now working on B.L. Stryker and arranged for Chiklis to meet with Reynolds. In a 2015 interview with the Television Academy Foundation, Chiklis says Reynolds told him he “didn’t believe in blackballing and thought I was a great talent, and he wanted to hire me, so he did.” Guest starring roles in some of the biggest shows of the time, like Murphy Brown, L.A. Law, and Seinfeld, followed. Networks were even considering him for his own show.

In 1991, he landed the starring role in The Commish, in which he played Tony Scali, the affable police commissioner of a small town in New York. He was encouraged to gain weight for the role; although he was in his late 20s when the show started filming, he was playing someone more than a decade older. The show ran for a successful five seasons, but Chiklis felt stuck, pigeonholed by the part. “Everybody thought that I was a 50-year-old, roly-poly nice guy.”

At his wife’s encouragement, Chiklis shaved his thinning hair and hit the gym, ready to reinvent himself. “At this point, no one would have hired me to play Vic Mackey. I did what I had to do to change minds,” he says. “It’s a very fickle industry. Listen to the lyrics of Frank Sinatra’s song ‘That’s Life’: ‘Riding high in April, shot down in May.’ That is exactly the life of an actor.”

Striking Gold

In 2019, the Guardian reminisced about The Shield, writing, “If you talk about the golden age of TV without mentioning The Shield, you’re doing it wrong.” The newspaper lauded the show for maintaining its quality all the way through its last episode and not petering out with a disappointing final season like other programs have. It praised Chiklis’ “magnificent performance” of a character who, despite his amoral deeds, still garners sympathy. Playing Mackey, which has arguably become Chiklis’ best-known role to date, was “an amazing, life-changing experience,” he says.

“We knew we were doing something special. It was artistically just such an incredible time. The show felt very relevant. It still feels so relevant because a question we were asking at the time through the show was, ‘What are we willing to accept from law enforcement in post–9/11 America to keep us safe?’ And, as it turns out, a lot of us were willing to accept way too much.”

Chiklis, a lifelong comic book fan, played The Thing in Fantastic Four and its sequel. 20th Century Fox

His turn as Mackey opened up other parts, like Ben Grimm/The Thing in Fantastic Four and Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (passion projects for Chiklis, a lifelong comic book fan) and more recent roles in American Horror Story: Freak Show and Gotham.

Soon, Chiklis will bring a Mackey-esque tough-guy edge to his starring role in the upcoming series Coyote, set to premiere on an as-yet undisclosed streaming service in early 2021. He plays Ben Clemens, a longtime US Border Patrol agent who, on the same day of his mandatory retirement, finds a tunnel used for smuggling black market goods into the United States from Mexico. Through a series of events, he becomes a coyote, someone who smuggles people across the border. Chiklis, who also serves as a coexecutive producer on the series, worked with the show’s director and executive producer Michelle MacLaren for more than two years to polish the series and get it ready for development.

In the upcoming Coyote, Chiklis plays US Border Patrol agent Ben Clemens. Like many shows and movies in 2020, Coyote's premiere was pushed to 2021, but Chiklis says it is worth the wait. Video courtesy Rotten Tomatoes TV

“This show is about a collision of cultures. It’s very timely, but the show is not political,” says Chiklis. Half of the show’s writing staff, he says, are South and Central American and Mexican, while the other half are from the United States. He is drawn to playing the complex Clemens, a character whose “viewpoint has been galvanized through echo chambers. But he starts questioning his views. It’s very disillusioning for him and very disorienting.”

Filming for the show started in November 2019, mostly around Baja California, Mexico, and Chiklis often faced rigorous shoots—including one that landed him in surgery. While shooting a scene in the Sonoran Desert during the first couple of weeks of filming, he was running up a mountain face and hopped over a prairie dog hole to avoid it. “Unfortunately, I landed right above the hole, where the tunnel was, and it collapsed. My knee completely hyperextended.” He kept going and finished the take. Although he knew he was hurt, he continued filming through the next few months with two tears in his meniscus.

Then, in March, six and a half episodes into filming, production had to suddenly shut down due to COVID-19. “We had to stop in the middle of this amazing experience that we were having. It was horrible,” says Chiklis. Still, he was inspired by how the cast and crew adapted.

“The postproduction on those episodes was done entirely remotely, which was just an extraordinary and arduous experience. But it was the only way to be able to do it. I really think this will change the way the industry does business in the future.”

Chiklis says filming Coyote brought back memories of making The Shield.

“Sometimes, when people watch something on TV, they’re watching with this benign, removed attention,” he says. But, he’s not interested in that. “I want to affect people. I want to make people feel something. It’s so satisfying when I make something that entertains people, but also gets them thinking, gets them engaged, and maybe makes them see things in a different way.”

The Paintings on the Doors

How muralist Lena McCarthy transformed a Victorian firehouse

By Marc Chalufour | Photos by Janice Checchio

"Every project is so, so different,” says muralist Lena McCarthy. She has painted murals in Chile, India, and Ireland, as well as the United States. She might paint a 100-foot brick wall one week and multiple sides of a concrete courtyard another. So when she accepted a commission to transform the front of a historic century-old firehouse 30 minutes from her home outside of Boston, McCarthy (’14) wasn’t phased by the challenge.

Jannelle Codianni, director of ātac, the community arts center that has organized exhibits and live performances in the Framingham, Mass., firehouse since 2008, gave McCarthy a lot of freedom with this project—but it was no blank canvas. The mural needed to span three large bay doors. Small window panes would interrupt the design while brick columns topped by iron sconces split it into three panels, creating a giant triptych. McCarthy would be trying to reflect themes of hope, connection, and resilience.

Over four hot days in June, muralist Lena McCarthy (‘14) transformed the front of a historic firehouse in Framingham, Mass., that now houses ātac, a community arts center.

Codianni wanted to hire a local artist and reached out to McCarthy, a past exhibitor at ātac, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We’ve been closed to the public since March and are preparing to start our fall season with virtual performances,” Codianni says. “I’m hoping the mural reminds people we’re still here, even if in a different form for now.”

The two met in April to discuss the project. Then McCarthy got to work.

Finding Her Way to the Wall

McCarthy’s mural career sputtered at first. She founded a mural club at BU, but it was a failure. “We only did one project,” she says, a mural in a Brighton park. The club disbanded after McCarthy graduated.

The fine arts major knew she wanted to paint, but graduated without an immediate career plan. “I was interested in traveling and seeing the world,” she says. She moved to Chile, where she taught English for two years. McCarthy immersed herself in Santiago’s active street art community. “It was a very stimulating environment,” she says. By the time she returned to Boston, she considered murals to be her primary focus.

To work as a muralist, McCarthy says she had to learn “how to be brave and put yourself out in the world and how to make connections with the community you’re painting in.”

McCarthy found that her fine arts training served her well in muralism. But there were still some new skills she had to learn, among them, “How to be brave and put yourself out in the world and how to make connections with the community you’re painting in,” she says. Helping her make that transition has been a series of mentors, including Cambridge, Mass.–based street artist Caleb Neelon, coauthor of The History of American Graffiti.

“There’s a lot of graffiti history intertwined with muralism,” McCarthy says. Part of that influence is the value of visibility—finding spaces that will be seen by the most people. McCarthy estimates she’s completed between 30 and 40 murals, and as she’s established herself, she’s begun considering other factors. “I’ve looked for more projects where the site has meaning, or the site has impact, like neighborhoods that don’t have as much public art.” Sometimes that means a work has an explicit social message: McCarthy collaborated with Neelon on murals in Queens, N.Y., of Gynnya McMillen, a 16-year-old who died in police custody, and Marsha P. Johnson, a gay rights activist who died under suspicious circumstances. McCarthy is planning murals for the playroom and garden at a home for teen moms.

Drawing from Within

Once McCarthy and Codianni had discussed the goals of the firehouse project, she began the same way she starts every project: pencil on paper sketches. “A sensation or a feeling of ‘hope’—that’s an infinite thing,” she says. “I tried to just draw from within myself, what I believe that would look like. It’s my interpretation of the language that they asked me to use.”

McCarthy expects her art to evolve once she begins to paint. “I always have to leave room for it to breathe—I never make things exactly as they look [in the sketch],” she says.

Accepting a commission means agreeing to some limitations. In this case, that meant sticking with ātac’s color palette. Fortunately, the teals and blues contrasted nicely with the building’s red brick. Some commissions involve several rounds of revision, but there was no micromanaging of this project. McCarthy presented four sketches to Codianni and the ātac board. Once they chose one, she imported her drawing into Procreate, an iPad app. Using an Apple Pencil, she refined the drawing, added colors that matched the paints she planned to use, and layered it onto a photo of the building.

“One of the main things I love about mural painting is it’s so in your body. It’s so cheesy but it’s true: You become the tool. You’re the brush.”

McCarthy expects her art to evolve once she begins to paint. “I always have to leave room for it to breathe—I never make things exactly as they look [in the sketch],” she says. McCarthy began her mural career using brushes and rollers, but she’s since moved to fine art spray paints, which allow her to work fast and cover just about any surface. Color selection is important—she can’t mix paints as an artist with a palette might. But, she says, “there are ways to blend and overlay colors.” McCarthy uses two types of spray can caps: a skinny cap creates fine lines while the versatile New York fat cap has a broader stroke for filling and shading. It can even create a mist effect. By adjusting her finger’s pressure on the cap, the can’s angle to the surface, and the speed of her arm, she can create different visual effects on the wall.

“One of the main things I love about mural painting is it’s so in your body,” she says. “It’s so cheesy but it’s true: You become the tool. You’re the brush.”

The Many Layers of a Mural

On June 17, McCarthy unloaded her Honda Civic in front of ātac and began painting. Then, over four hot days, she transformed the façade of the firehouse.

McCarthy worked within ātac’s color palette of teals and blues, which contrasted nicely with the building’s red brick façade.

McCarthy’s gear, beyond the 22 cans of spray paint she had estimated she would need, is limited. She has an adjustable ladder and sometimes uses a piece of cardboard as a straight edge. And, she says, “A friend gave me a really nerdy muralist’s tool belt that I wear [so] I can hold six spray cans.”

“On the first day, the goal is to get ready to paint,” McCarthy says. She scrubbed the wooden doors and laid out some of her design’s straight edges with a chalk line. Then she sketched the more organic shapes with spray cans. She also used a paint roller on an extension arm to draw on the wall from a distance so she could see what she was doing.

When she returned the next morning, she began covering the doors with paint. She filled in dark background colors, then began layering on lighter shades. Over the next three days, the contours of her design took shape. Three tiered triangles extend toward the center of the building while the natural curves of leaves and grass blades spring up behind them.

McCarthy began her mural career using just brushes and rollers, but she’s since moved to fine art spray paints, which allow her to work fast and cover just about any surface.

Some muralists project their design on a wall to provide a guide, others use stencils. “I’ve never been a very exact person,” McCarthy says. “I just go for it, and if it’s wrong, I fix it. I think the organicness of my stuff lends itself to that method.”

She checks her work frequently, though, backing away from the wall and asking, “‘What did that stroke just do to the whole thing?’ It’s kind of like this dance back and forth.”

After working her way to the lighter end of the spectrum, it was time for some final flourishes. “I make some wispy lines that weave through everything,” McCarthy says. “And I do some starburst-like dots. Those are the last little highlights that make it sparkle.”

The Art of Inclusion

McCarthy’s completed mural evokes a moonlit scene. A dark sky emerges from the recesses of the doors’ arches. Grasses reflect light and bend in a gentle breeze. Delicate dandelions appear ready to release their seeds. “I’m using organic forms to convey a sensation,” she says. “I wanted it to feel like there was a light or an energy coming from within the space.”

Floral elements permeate McCarthy’s murals. “There’s a really strong male energy in graffiti, and my work can have a more feminine vibe,” she says.

Scroll through McCarthy’s Instagram account, @lenamccarthyart, and you can see why she uses the word organic to describe her work. Floral elements permeate her designs. A mural in Cambridge, Mass., features a red heart sprouting colorful leaves and branches. Female figures are also a frequent motif. “There’s a really strong male energy in graffiti, and my work can have a more feminine vibe,” she says.

Reflecting on the difference between her outdoor work and studio paintings, McCarthy says, “There’s something about public art and muralism that’s so inclusive.” No curator has chosen where to hang the painting. No museum guard stands nearby. “You’re injecting color in your neighborhood—it’s fun, it’s energy. We should live our lives surrounded by art all the time,” she says. “To me, that’s a no-brainer.”