Book Reviews

Book Reviews for Fall 2009

Balkan Caesar: A Novel of World War II

Peter Lucas (CAS’60) Fiction (Aberdeen Bay)

Two years after publishing a history of America’s involvement in pre-Communist Albania during World War II, Lucas returns to the topic, this time with a fictionalized account. The inherently dramatic story is a natural for fiction: Office of Strategic Services operatives, here a motley crew of Bostonians, are given the task of undermining Hitler in Albania. That means working with the charismatic but brutal Albanian Communist Enver Hoxha, real-life leader of Albania from the end of the war until his death in 1985, in a morally ambiguous mission many come to regret after Hoxha’s rise to power. “You can’t make a movie these days about being on the wrong side,” laments one character, an OSS member-turned-actor, as the Cold War kicks into gear. Maybe not, but between Lucas’s dedication to the subject and the book’s endorsement from Albanian-American director Stan Dragoti, anything’s possible. ~Katie Koch

Camping Day

By Patricia Lakin (DGE’63, SED’65) and Scott Nash Fiction (Dial Books for Young Readers)

Crocodile friends Sam, Pam, Will, and Jill are back for their fourth adventure, and this time they’re taking to the woods. Off they dash, with maps, packs, lights, and tent. On their hike, they pause to check out the view, the flowers, the birds, and the trees. But when they settle in for the night, the strange sounds and shadows set their imaginations racing, and soon they’re running for the safety of their van. All is not lost, though. They find a way to spend a night under the stars.

Camping Day is the latest in a series of picture books featuring these happy critters, with text by Lakin and cheerful illustrations by Nash. ~Cynthia K. Buccini

Repeat After Me

By Rachel DeWoskin (GRS’00) Fiction (Overlook Press)

With the 2005 publication of Foreign Babes in Beijing, an account of her brief career playing an American temptress on a popular Chinese soap opera, DeWoskin proved to be an accomplished memoirist. Now, in her debut novel, Repeat After Me, the graduate of BU’s Creative Writing Program again draws on her insights into contemporary Chinese culture.

Set in 1990s New York and in Beijing a decade later, Repeat After Me is the story of Aysha, a young English as a second language teacher who falls in love with Da Ge, a Chinese dissident enrolled in her class. At twenty-two, Aysha is moderately obsessive-compulsive, with one nervous breakdown behind her, making Da Ge’s direct speech and straightforward pursuit of her appealing. But as their relationship develops, Da Ge’s own family conflicts and experiences with mental illness throw up personal and cultural roadblocks. A decade passes before Aysha, now living in Beijing with her daughter, truly begins to understand her former student.

DeWoskin’s funny and probing memoir examined the linguistic and cultural boundaries she encountered living in Beijing, and she allows Aysha to follow in her footsteps, most memorably through the emerging friendship of Aysha and another Chinese student, Xiao Wang. The two watch movies from Aysha’s childhood — Dirty Dancing, Pretty in Pink — together.

“I realized I had never noticed anything about my own culture until Xiao Wang sat me down on my couch and showed me the movies I was showing her,” DeWoskin writes. “She and Da Ge were the first people who ever forced me to pay attention, to look out and see in.” ~Jessica Ullian

Spoon

By Robert Greer (SDM’73,’74, GRS’89) Fiction (Fulcrum)

Besides being a University of Colorado professor and pathologist and author of nine mysteries, Greer is a rancher, and his new novel is about the love of the land that makes small family ranches viable still.

The Darleys are struggling to keep their Montana ranch going (on land granted the family by Warren G. Harding) despite the traditional opposing forces — hard economic times and drought — and a contemporary villain, a large energy company wheedling, bullying, and cheating neighboring ranchers out of their mineral rights and often their land. Then Arcus Witherspoon (“It’s Spoon, ma’am”) appears, looking for work as a hired hand. Half black and half Indian, he has a rancher’s mechanical skills, a loving way with animals, and an appetite for hard work, plus a mix of other abilities and knowledge and a mysterious clairvoyance that defeats natural and human adversaries.

Since we know all along the ending will be happy, it’s not spoiling the considerable reading pleasure to say that big business loses, teenaged TJ Darley declines his college scholarship to continue working on the ranch, and Spoon rides off into the sunset, perhaps to fight elsewhere for truth, justice, and the American way. ~NJM

The Day We Lost the H-Bomb: Cold War, Hot Nukes, and the Worst Nuclear Weapons Disaster in History

By Barbara Moran (COM’96) Nonfiction (Presidio Press)

On January 17, 1966, a U.S. B-52 bomber carrying four hydrogen bombs exploded during a midair refueling over the village of Palomares, on Spain’s southeastern coast. The accident killed seven airmen and scattered the bombs, each with seventy times the explosive power of the one that destroyed Hiroshima, over land and sea. The flight was part of a USAF Strategic Air Command (SAC) program called airborne alert, the goal of which, Moran writes, many believed was to keep the Soviets in check. At the time, SAC controlled most of the nation’s nuclear warheads, bombers, and missiles. “Their influence was so great that it seemed perfectly reasonable — even necessary — for pilots to fly toward Russia, during peacetime, with four hydrogen bombs in their plane,” she writes.

The search for the four bombs — three were quickly located, and the fourth was found at the bottom of the ocean two months later; none had exploded — cost millions and was the most expensive salvage operation in history.

It also sparked some soul-searching among the public. “Suddenly,” according to Moran, “the 32,193 warheads stashed around the country seemed less like a security blanket and more like a loaded gun with the potential to misfire.” ~CKB

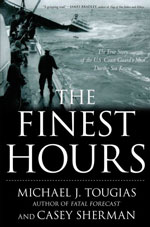

The Finest Hours: The True Story of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Most Daring Sea Rescue

By Casey Sherman (COM’93) and Michael J. Tougias Nonfiction (Scribner)

In February 1952, long before the Andrea Gail’s last fateful trip, another perfect storm assaulted the Massachusetts coast. Amid seventy-foot waves, not one but two oil tankers (both made from shoddy steel) split in half in the freezing Atlantic. That a majority of the ships’ eighty-four crew members survived, Sherman and Tougias write, testifies to the bravery, and luck, of the Coast Guardsmen in sleepy Cape Cod towns who undertook the rescue.

Aboard thirty-six-foot cutters — the Coast Guard lacked waterproof clothing, much less helicopters — rescuers overcame poor communication, punishing weather, and cramped quarters, in one case bringing back thirty-two survivors in a boat meant for four.

Sherman, author of the Boston Strangler chronicle A Rose for Mary, and Tougias, a writer of maritime-disaster histories, came to the story separately, but as with the men they profile, their efficient teamwork pays off. A brisk read, The Finest Hours grippingly recounts a clash of man, machine, and Mother Nature in circumstances where, as the book acknowledges, the outcome was far from certain. ~KK

The Little Book on Meaning: Why We Crave It, How We Create It

By Laura Berman Fortgang (COM’85) Nonfiction (Tarcher)

This once-aspiring actress uses her training as an interfaith minister, her practice of meditation, and her experience as a wife, mother, and friend to help readers find meaning in their lives by recounting tales that proved especially meaningful in her own. Quoting religious figures and intellectuals, including Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel (Hon.’74), Boston University’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, Fortgang offers advice while reasoning that there is always room for improvement and growth. ~Brittany Rehmer (COM’11)

Sisters in War: A Story of Love, Family, and Survival in the New Iraq

By Christina Asquith (CAS’95) Nonfiction (Random House)

Asquith, who has written for the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer, spent two years on assignment in Baghdad before writing Sisters in War. In 2004, she was forced to hide in the Baghdad home of female friends as the situation for journalists grew more dangerous. There, she had a perfect vantage point for observing the effects on Iraqi women of limited electricity and water, the constant fear of a suicide bombing, and the inability to leave home without a male escort.

She writes about a woman who tells her two young daughters that Iraq used to be a “paradise” for women. But Saddam Hussein’s regime brought abuse and the end of women’s rights. The Iraqi people trusted that the American occupation would help restore peace and order, but as the war progressed, the Americans were unable to control the rising insurgency and secure the country.

Asquith focuses on four spirited women — two Iraqi sisters, an ambitious U.S. soldier, and a U.S. aid worker — fighting for Iraqi women who endure physical and mental abuse and have no legal rights and little education. ~Amy Laskowski

The Slave Next Door: Human Trafficking and Slavery in America Today

By Ron Soodalter (CAS’68) and Kevin Bales Nonfiction (University of California Press)

“It is right that we should never forget the horrors of antebellum plantation slavery,” write the authors of The Slave Next Door. “But if all we can see when we hear the word slave is a picture from Gone with the Wind, our eyes will be shut to the slaves of the present.”

Domestic workers put on punishing schedules without pay, migrant farmworkers forced to work for free to repay those who smuggled them into the country, and teenaged prostitutes — all examples of why slavery isn’t a thing of the past, according to Soodalter and Bales. Throughout the book, they demonstrate how easy it is to ignore modern-day slavery and how often it intersects with our daily lives. “Slavery probably crept into your life several times today, some before you even got to work,” they allege. The coffee beans in your morning cup might have been picked by slave laborers in Africa; the cotton T-shirt you wear could be the product of slave labor from India, West Africa, or Uzbekistan. Even your cell phone could be tainted — most use the mineral tantalum, often dug by poor farmers in the Democratic Republic of Congo enslaved for that purpose.

The authors intersperse heartbreaking stories with grim facts: trafficking cases are notoriously hard to prosecute, since they require proof of psychological coercion, so there’s a wide disparity in penalties for offenders. They call for more consistent state antitrafficking laws, more federal accountability, and greater public awareness, even at the neighborhood level. They write, “If you or I live in a community without slavery today, it is possibly because someone in the past turned to his neighbor and said, ‘This must end.’” ~JU

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Post Your Comment