BU Neurologist’s New Book Explores Tales Our Brains Tell Us

Pria Anand’s The Mind Electric is a sweeping yet intimate look at the mysteries of the brain

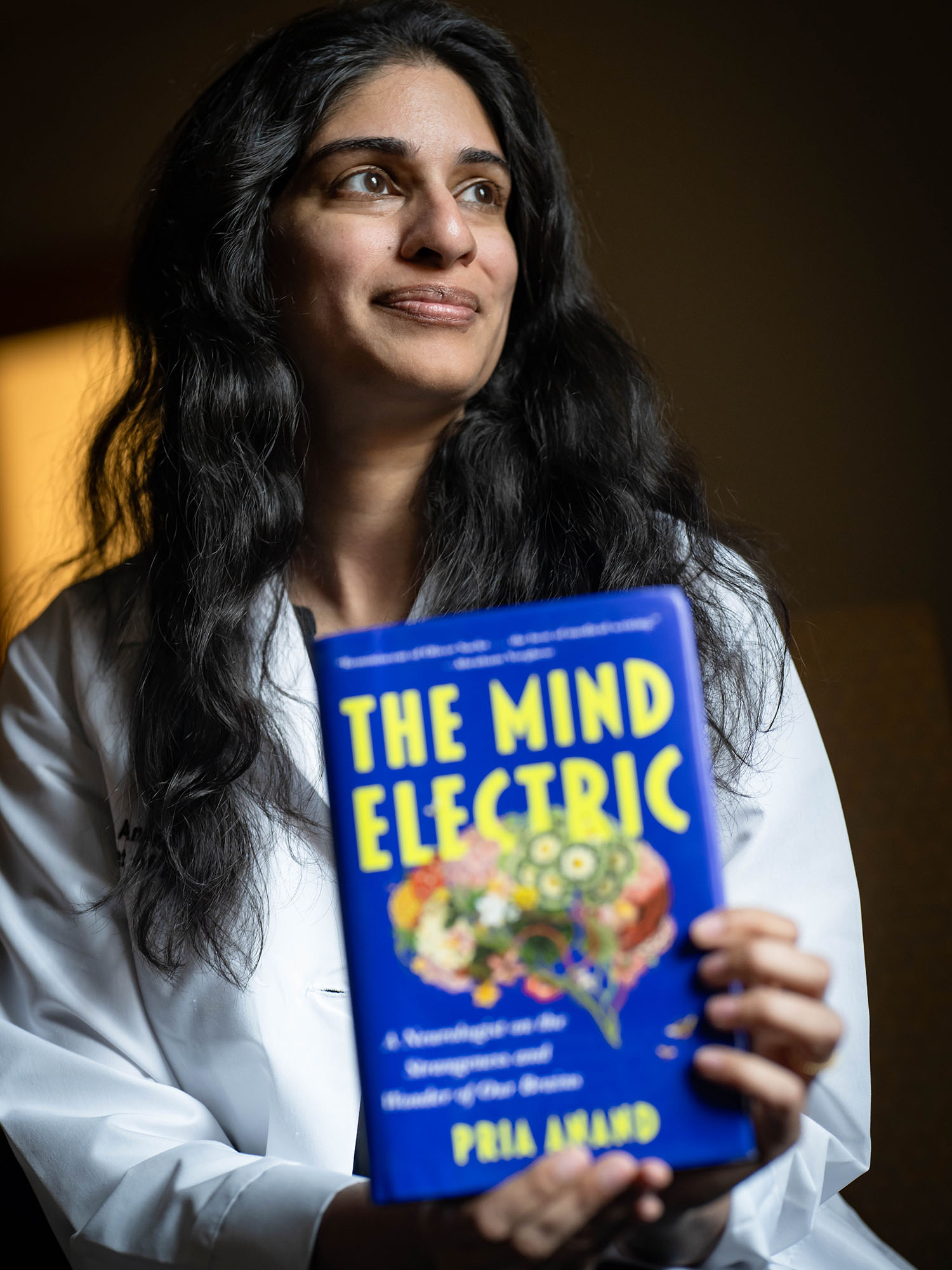

Pria Anand, a BU assistant professor of neurology, is director of Boston Medical Center’s neurology residency program. In April, she received the A. B. Baker Teacher Recognition Award from the American Academy of Neurology. Mentoring young doctors, she says, helps her stay grounded in the awe that first drew her to medicine.

BU Neurologist’s New Book Explores Tales Our Brains Tell Us

Pria Anand’s The Mind Electric is a sweeping yet intimate look at the mysteries of the brain

When neurologist Pria Anand began her medical training, she often worried that she was relying too heavily on her patients’ personal stories of their ailments and not enough on their lab results. Today, she views it differently—she’s come to understand that these personal narratives are crucial to gaining a comprehensive picture of the issues a patient faces.

“I’ve learned to piece together diagnoses not only from the involuntary tells of the body,” says Anand, an assistant professor of neurology at Boston University’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, “but also from the ways people choose to tell their story, informed by what they value, what they love, what their illness has taken from them.”

In her debut book The Mind Electric: A Neurologist on the Strangeness and Wonder of Our Brains (Washington Square Press, 2025), Anand explores how storytelling shapes our understanding of illness. Blending clinical anecdotes, historical case studies, and even tales from Arabian Nights, the book offers a sweeping yet intimate look at the mysteries of the brain and the power of narrative in medicine. Reviewers liken it to the writing of Oliver Sacks, Publishers Weekly calls it engrossing, and The Telegraph superb, noting that Anand “writes with circumspection and sensitivity, and with creativity and verve as well.”

Before entering medicine, Anand had once considered a career in journalism. In college, she briefly worked as a medical caseworker for incarcerated people reentering the community. “I really loved the experience of interviewing people and the idea that that could be alchemized into something bigger or more universal,” she says. “It engaged with this social conscience that I was interested in, and I think I was surprised by how much the medical aspects of the job moved me and stimulated me. I became interested in the way that science could be a part of changing someone’s story.”

In the book’s introduction, Anand discusses the neurological phenomenon of confabulation—when people unknowingly create false memories to fill gaps in their cognition, often due to dementia, strokes, tumors, or vitamin deficiencies—“an inevitable response of wounded brains,” she writes.

She’s fascinated by the idea that people can lose so much, yet still tell stories. “Even though I was taking care of people who had really esoteric illnesses,” she says, “it felt like there was something universal about human beings, and how we make meaning in our world.”

Take, for example, sleep paralysis. Patients often describe it as a dreamlike state of immobility, sometimes accompanied by an eerie figure or a strange noise. “I could tell you exactly what’s happening in your spinal cord when you have sleep paralysis,” Anand says, “but that doesn’t capture what it feels like to be paralyzed and see a shadowy figure. Every culture has a way of explaining it, whether it’s a witch or a sorcerer or a dissatisfied spirit. It felt like there was a truth in that, [that these stories] complemented the truth of my textbook.”

Anand emphasizes throughout the book that every diagnosis is rooted in a story. She tells of a student who lost her vision and believed it was divine punishment for the first kiss she had received a week earlier. Her diagnosis? A rare complication of Epstein-Barr, the virus that causes mononucleosis. Another woman, dismissed as having psychosomatic symptoms when she claimed her husband was poisoning her, was later found to have encephalitis.

Anand also reflects on her own experiences of illness, especially during her two pregnancies. She writes vividly of restless legs, sleeplessness, searing round ligament pain, and acid reflux. Like many women, she also faced skepticism from medical professionals. Alongside her personal tale, she delves into the historical mistreatment of women, including the dark legacy of Salpêtrière, the 17th-century Parisian asylum where women with mental illness, physical disabilities, and even pregnancy were often subjected to inhumane treatment.

“Doctors are less likely to treat women’s pain, particularly the pain of Black and brown women, less likely to diagnose common diseases in women than in men, less likely to believe women’s symptoms,” Anand writes. “Doctors, in short, are skeptics when it comes to the bodies of women.”

She is also critical of the language used in clinical settings. “In medical notes, words such as complain or deny sometimes read like harmless jargon, but in the real world of illness, language has stakes… A burgeoning movement in medicine advocates for a shift in language from complaint to concern,” she writes. Sometimes this charged language leads patients to be afraid to be truthful about their symptoms.

It’s a lesson Anand carries with her today, as director of BMC’s neurology residency program, where she oversees 28 students. In April, she received the A.B. Baker Teacher Recognition Award from the American Academy of Neurology. Mentoring young doctors, she says, helps her stay grounded in the awe that first drew her to medicine.

“Our bodies are miraculous, and I think the longer that you’re a doctor, the easier it is to forget that,” she says. “[But] for the person you’re taking care of, it [might be] the worst day of their life, and for you, it’s like just another day. And I think working with people who are newly inaugurated into the world of medicine is a good reminder of what is unusual about the work that we do.”

Anand completed her fellowship in neurologic complications of infectious diseases and autoimmune neurology, and today sees patients of varying socioeconomic backgrounds at Boston Medical Center, the largest safety-net hospital in New England. “We care for a lot of asylees and refugees, and so I see a lot of people from all over the world with a whole range of different exposures,” she says, and that is part of what makes BMC special.

Ultimately, Anand hopes that The Mind Electric will appeal to a broader audience drawn to a complexity of stories often overlooked in medicine.

“I’m thinking about people who are marginalized and the ways that we can serve them better,” she says. “I hope that this book speaks to a broader range of experiences that many people in the world have been exposed to.”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.