A Paper Strip Test for TB?

BU engineering postdoc demos promising portable diagnostic

Diagnostic tests for tuberculosis usually involve chest X-rays, which require heavy and expensive equipment, or phlegm samples, which can take weeks to culture. In resource-limited countries where TB is endemic, such tests are hard to come by outside of major cities, leaving health care workers with few good options. The simplest is a TB test that works like a home pregnancy test, diagnosing the disease based on the detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM), a biomarker for TB present in the urine of TB-infected individuals. Although the test is cheap, easy to use, and can be administered at the point of care, it produces accurate results only for patients who are also infected with HIV, since LAM is more abundant in their urine.

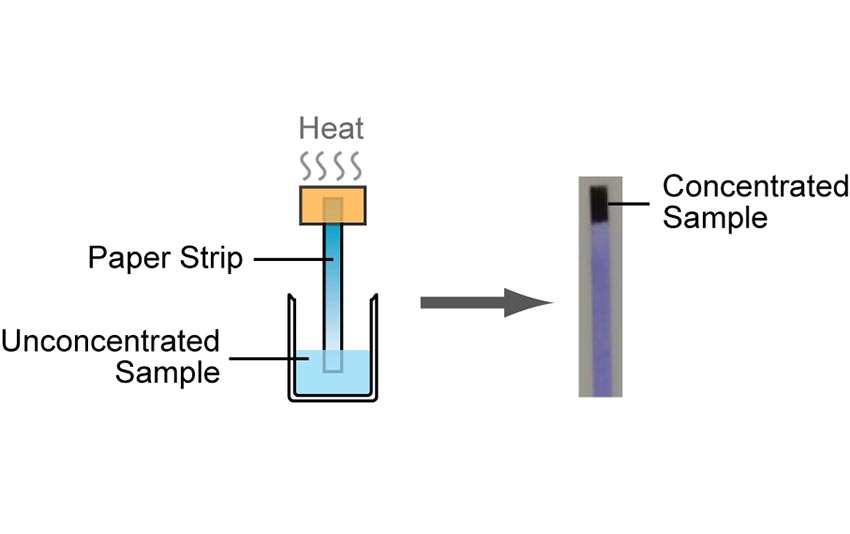

Now Sharon Wong, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Boston University Associate Professor Catherine M. Klapperich (biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, materials science and engineering), is working toward a similar inexpensive, user-friendly test that can overcome this limitation and serve the general TB population at the point of care. By applying heat to a strip of chromatography paper dipped in a urine sample, the device would concentrate LAM while evaporating most of the liquid sample. As a result, the low levels of LAM in non-HIV patients’ urine, which don’t register in the commercially available test, are increased and can be more easily detected.

Described in the December 16, 2014, online edition of the American Chemical Society journal Analytical Chemistry, the new test is the first to demonstrate the use of heat on a paper-based device for the purpose of quickly concentrating biological material for clinical analysis. Wong developed the test in collaboration with Klapperich, Research Assistant Professor Mario Cabodi (biomedical engineering), and Jason Rolland, the former director of research at Diagnostics for All, a Cambridge-based nonprofit focused on low-cost, user-friendly, point-of-care solutions for the developing world.

“This protocol that Dr. Wong has developed has the potential to increase the utility of one of the most simple and inexpensive methods to detect TB,” says Klapperich. “Strip tests are easy to use and understand and could positively impact patient care in many low-resource settings.”

In lab tests, Wong diluted a small quantity of LAM in a sample of synthetic urine in a beaker and inserted one end of a piece of chromatography paper into the sample. The urine wicked up the paper until it reached the other end, which was warmed to 220 degrees Celsius by an electric heater. Most of the urine evaporated off within 20 minutes, leaving a concentrated amount of LAM at the tip of the paper strip. Using an antibody that binds to LAM, Wong then determined that the biomarker was 20 times more concentrated at the tip than at the end submerged in the sample.

“After spending months trying different ways to heat the paper, this was my last-ditch effort,” says Wong. “So it was very exciting when it finally worked. I can now envision, in the foreseeable future, a TB diagnostic that can be used on anyone, by anyone, anywhere in the world.”

Wong’s next steps include optimizing the system by fine-tuning the heating temperature and duration, paper strip dimensions and other variables; validating it on clinical samples; and identifying other unplugged power sources, such as batteries, to make it portable. Beyond the lab, she envisions a test that not only indicates the presence of TB with a single line, but also shows higher concentrations of LAM with additional lines. This extra information could enable clinicians to easily track the effectiveness of drug treatment for the disease over time.