My First Year in Fifth Grade: A Teach for America Diary

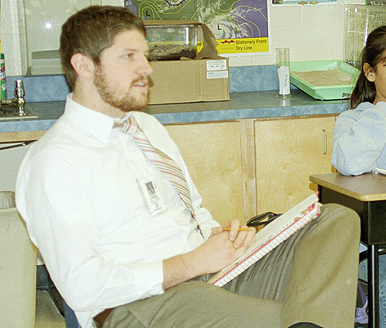

Cole Farnum left Commonwealth Avenue for Brownsville, Tex., when he joined Teach for America after graduating from BU. In this series, taken from letters to his family and friends, Farnum (CAS’06) recounts his first year in the classroom. Check BU Today each day this week to read about beginnings, endings, and the ups and downs in between. This year’s Teach for America application deadline is November 2; e-mail TFAatBU@gmail.com. Click here to read part one.

I just got a new student, and she is on grade level — a surprise, since late-fall admissions are usually straight out of Mexico, knowing little of the curriculum and speaking very little English. This girl attended my school the previous year, and has just switched back. So she is fitting in well.

I’m also fitting in: my professional appraisals have been completed, and I did very well. Many people have dropped by my class to observe and take notes on my teaching style, and all have come back with praise and helpful comments. It really helps when I remind myself that they’re there to make me a better teacher — not to catch me not doing my job. Even my mom stopped in when she visited in October. The things that go through kids’ heads are hilarious: “Sir, was that your sister?” ”Sir, was that your girlfriend?” ”Sir, was that your grandmother?” Like I’ve said, the good times are those that make me smile.

What the walk-throughs don’t see are the daily struggles. Sometimes I find myself demanding a lot of my students, more so than the other teachers. I expect them to do their homework, and if not, there are consequences. If it happens more than once, there are more consequences. One student has a limited understanding of this concept. He cried when I confronted him with his missing assignments, and stared me down with clenched fists. His third grade teacher, at another school, he told me, said openly in class that he was retarded, and this incident has had a lasting effect on him. Since then, he has fundamentally distrusted his general education teachers, and I have been no different. It is so hard to connect with him, since most of the day he is outside of the classroom for resource math, reading, and writing. I want him to be part of the class, but he needs so much special attention that I am honestly not certified to give him. And so he barely interacts with me, except when I have to address what he is responsible for.

Just because I have been to college and accepted into Teach for America does not make me certified to deal with the daunting realities inside a public school. But I’m here and I’m trying.

My heart goes out to the special education teachers — they have the real tough jobs. Based on what a friend at a nearby middle school tells me, the most difficult job is special education inclusion — you go from class to class to monitor every student, each of whom is being exposed to something above his or her capabilities, with different goals according to his or her own individual education plan (IEP). Some students are striving to master 70 percent of the material, some 50 percent, and some to keep their heads off their desks for the duration of the school day. It’s all different and individualized and almost impossible for one teacher to manage. Inclusion teachers help out with this, but there is only one inclusion teacher in my friend’s school for each grade level. This means one teacher has 60 students in different classes. It makes my responsibilities seem like mere chores.

Teaching is almost inequitable, in practice, due to the state testing. As an educator whose efficacy is judged on a state exam score average, I need to put my energy towards the children who are most likely to pass or who failed the tests last year by a small margin. We call these kids the “bubble students.” They are the easiest kids to pull into the next grade. This is the smart way to do it — or the way that will make you look like a better teacher since the scores will be higher. But then, have you done your duty towards the children? It’s hard to tell, and it’s something that I think about constantly. I don’t think I will ever come to the conclusion that I did everything I could have. What happens if you do this for one child — is that equitable to the whole class?

I cannot say that I’ve solved the puzzles of teaching, but I have learned how to deal with them in some ways. Some of the injustice you see or the inefficiencies you experience must simply be accepted until you have the time and the energy to spend on them. You have to live with things you find completely wrong. It’s the only thing that you can do for the time being.

Cole Farnum can be reached at cole.farnum@corps2006.tfanet.org.