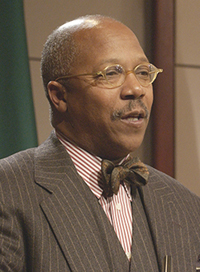

APARC director will receive two honorary degrees

Q&A: Ambassador Charles Stith says Africa needs help from African-Americans

Former U.S. Ambassador to Tanzania Charles Stith, founder and director of the African Presidential Archives and Research Center (APARC) at Boston University, returned from Africa last month to learn that he had been awarded honorary degrees from two prominent Southern universities in recognition of a career as a minister, a civil rights activist, and a civil servant. Stith will receive an honorary doctorate from the University of South Carolina on May 5 and one from Clark Atlanta University on May 15.

Stith had been in Johannesburg, South Africa, attending the fourth annual African Presidential Roundtable, which was organized by APARC and hosted by the University of Witwatersrand. The two-day conference, on April 20 and 21, brought together former African presidents from Botswana, Burundi, Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, and several other countries to discuss the progress and the needs of sub-Saharan African states, with particular focus on two issues: the continent’s image in the American media and the engagement of Africa’s Diaspora in the development of Africa. Stith spoke with BU Today about APARC’s mission and Africa’s needs.

BU Today: What exactly is the problem with Africa’s image in the American media?

Stith: The preponderance of media coverage is overwhelmingly negative. It’s about disaster and disease and destruction from war. That’s a problem for the continent because it’s through those lenses that the average American sees the continent. So there is reluctance to invest and reluctance in terms of tourism.

Is there a disconnect between the reality of Africa and the image presented by the American media?

Well, you don’t see stories about South Africa, which since elections in 1994 has experienced the longest period of sustained growth in its history. There are no stories about the increased investment in education in Ghana or Botswana or the development in downtown Dar es Salaam in Tanzania or the five-star resorts in Mauritius. And there are other opportunities for tourism people aren’t aware of.

What are the reasons for this disconnect?

Part of it is the press’s rule that “if it bleeds, it leads.” That kind of mentality in the popular media is one reason, and the other is just laziness on the part of reporters covering the continent. It’s easier to cover disaster, disease, and destruction than to battle with editors who have preconceived notions about the continent.

What can be done about it?

I think it’s important for reporters to develop strategies to counter the deluge of negative coverage, but a main goal of our conference was to look at ways to re-brand the coverage and market Africa better. It’s important for institutions like Boston University and the College of Communication, which can look at training future journalists, to cover developing countries so they have a better understanding of context and the content of what’s going on in some of these places.

There was a piece this week on the front page of the New York Times reporting on the 900 percent inflation rate in Zimbabwe. Harare is described as a place that suffers from electrical blackouts and a place where cholera and dysentery sweep through the streets. Is there something wrong with that coverage?

It’s the same story. Substitute the headline, white-out the name of the country. But you don’t read about inflation rates that had double digits in Tanzania in the 1980s but are in the low single digits today. There are positive economic indicators in South Africa, such as the millions of units of housing that were built for people who were displaced during apartheid, and yet we hear the same story over and over.

Why does it matter what the American media write?

It would make a difference in a way as simple as giving Americans a willingness to tour the continent. Folks don’t appreciate its wonders. Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge is home to some of the oldest human remains ever found. Mount Kilamanjaro is the rooftop of Africa. That drive from Victoria Falls to Cape Town rivals a ride on the Orient Express.

The roundtable also discussed engaging Africa’s Diaspora in the continent’s development. What does that mean — engaging Africa’s Diaspora?

It means leadership on the continent having very specific strategies. It’s not enough to say, “Here’s the welcome mat, come on in.” It means getting people to appreciate that Africa is more than the sum of its problems. Tourism is a source for hard currency. It can significantly and exponentially grow that sector, creating incentives for investment. The African-American community has an annual aggregate income of $750 billion a year. If one percent of that were harnessed in terms of Africa’s development, it would be huge. That represents more than we send in foreign aid to the entire continent.

In what ways might it be engaged?

One thing that is critical is that as African leadership comes to this country, they make a specific effort to reach out to African-American communities. When they are in the UK they make a specific effort to reach out to Africans in London, because those folks have tremendous skills and tremendous resources.

What are the obstacles?

Understanding that is an important point of our roundtable. We began to walk leadership through the benefits, the upside of engaging the African Diaspora in development, and brainstorming about ways to do that. The primary impediment is folks’ appreciating the need to do it.

What is the plan?

Our mission at APARC is pedagogical. We want to create a forum to help them engage one another. Our hope is that more former heads of state and retired senior officials in multilateral organizations engage and pick up the mantle on these issues. Our mission, in terms of providing a forum and data to discuss these sorts of things, has been fulfilled.