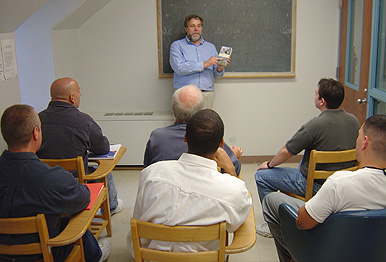

Prison Education Program expands with new grant

Bridge to College prepares inmates for degree programs

Boston University’s Prison Education Program (PEP), run by Metropolitan College, has thrived for more than three decades despite the ongoing difficulty of finding inmates with the requisite college courses to qualify. But MET Dean Jay Halfond says a new grant should solve that dilemma.

The $180,000 grant, from the Lynch Foundation — founded by Peter Lynch, a president at Fidelity Investments, and his wife, Carolyn — will support a two-year pilot Bridge to College program. Each year 75 prisoners can be enrolled in courses aimed at addressing the specific needs of first-year college students. Those who pass all the courses will be eligible the following year to enroll in regular PEP courses.

“This is designed to broaden access and exposure to higher education in state prisons while ensuring the academic standards of the Prison Education Program and the success of the students,” says Halfond. “It will allow us to expand the program and move more prisoners towards college degrees and more constructive lives.”

A 50-state analysis released this month by the Institute for Higher Education Policy shows that postsecondary courses are available to only 5 percent of the U.S. prison population. A majority of prisoners involved are taking vocational courses and are not earning college degrees, even at the associate’s level, in any significant numbers. BU is one of only a few private, four-year institutions working inside prison walls.

In 1972, under the leadership of President John Silber, BU began offering college-level liberal arts courses to Massachusetts prison inmates on the proven premise that education curbs recidivism. Over the next two decades, support from federal Pell Grants available to prisoners spurred the University of Massachusetts, Curry College, and several community colleges to offer courses in prisons. These courses served as feeder programs for PEP. But when Congress eliminated Pell Grants in 1994, most participating colleges bailed out — including all Massachusetts colleges except BU.

“Our enrollments began to drop in the late ’90s as students either graduated or were released, and fewer new students could meet the qualifications of the BU program,” says Robert Cadigan, a MET professor, who teaches in the program. Enrollments gradually increased, he says, because of a probationary admissions policy created in 1999 by Carl Sessa, a MET assistant dean, and efforts by groups such as Partakers, Inc., to help potential students meet admissions requirements.

“But because of the exodus of the other Massachusetts schools, incarcerated students have not been able to secure the freshman-level transfer courses needed to be admitted to BU’s program,” says Halfond. “This grant will enable us to broaden our reach and impact more lives. These students are highly motivated and appreciative, and we can see the direct benefit we bring to them and to the community they hope to reenter.”

BU is among only about a dozen schools nationwide teaching credit courses inside prison walls (others offer correspondence courses). This year 180 students are enrolled in 22 PEP courses at the Norfolk, Bay State, and Framingham state correctional institutions and at the South Middlesex Correctional Center.