Cuba Gets a New Normal

Normalized diplomatic relations a vital first step, BU expert says

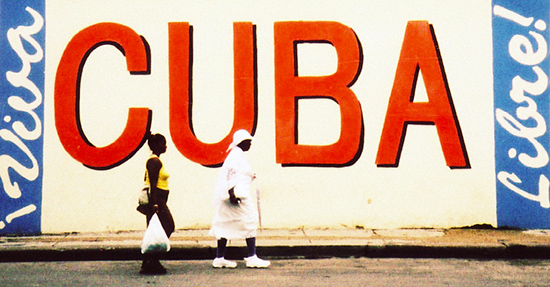

Diplomatic relations with Cuba will hasten the “post-Castro era,” BU’s Paul Hare predicts. Photo Courtesy of Flickr Contributor Flippinyank

An irony worthy of the ancient Greek writers lay in President Obama’s December decision to restore diplomatic relations with Cuba: ending an isolation that was intended to hasten regime change on the island nation could finally summon that change.

So says Paul Hare, former British ambassador to Cuba and a visiting lecturer at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, who argues that diplomatic relations mean Cuba’s “whole revolutionary ideology will need to change, and many in Cuba will see the post-Castro era as much closer now than before December 17th.” The revolution begun in 1959 by former president Fidel Castro is “in transition,” Hare says, with the country’s resources strained by heavy state spending and a likely cut in subsidies from its benefactor, Venezuela. Meanwhile, says Hare, current president Raul Castro, Fidel’s brother, has failed to map the country’s economic and political future.

Diplomatic recognition will allow family trips, public performances, and travel for professional, educational, and religious purposes to Cuba. It will also permit US credit and debit cards to be used there. But tourism remains banned, and the US trade embargo against the island will stand until Congress agrees to repeal it.

BU Today asked Hare to parse the economics and politics of the momentous decision.

BU Today: Do you support President Obama’s action?

Hare: Yes, very much. President Obama has signaled a new direction in US policy to Cuba—away from regime change and more to one allowing a full US diplomatic presence on the island, which will promote economic and political openness.

The president can’t unilaterally lift the US trade embargo against Cuba. So how big a change will this be?

President Obama is chipping away at the block. The whole edifice will take a lot of dismantling. Previous presidents have used their executive power to make adjustments to the embargo. What he can’t do is bring down the whole Helms-Burton legislation [stiffening the embargo]. That has to be by Congress. And from January 2015, the Republicans control both houses. So free trade and investment is still some way off. Helms-Burton states that no official US assistance, such as development aid, can be given to Cuba as long as Fidel or Raul Castro is in the government. What Obama is doing is making travel under license easier, authorizing use of credit cards, some banking facilities, et cetera. But free travel to Cuba by all Americans is some way off.

Critics say the president’s decision rewards Cuba for remaining a dictatorship.

Human rights remain a problem, but the US will find allies who have full diplomatic relations with Cuba—like the UK, Germany, Spain, Canada, Mexico, and Brazil—who all have an interest in promoting more openness and tolerance of diverse views in Cuba. So being a full diplomatic player like these other countries will mean the US has to develop a wide-ranging foreign policy with Cuba, which includes elements of engagement but also, like the EU, elements of criticism. That is what diplomacy is normally about. And now the US will be treated as a full diplomatic mission. The opposition and civil society [organizations] like the churches will feel they have more “space” in which to operate. They will have a more powerful ally in the US, which is no longer seen by Cuba as its enemy. They know that any new crackdown on them would jeopardize Cuba’s new relations with the US.

Will the new relationship have any economic effect on the Cuban economy—or the US economy?

It should have a big effect eventually. The immediate easing of travel restrictions, use of US-issued credit cards, and NGOs [allowed to] open bank accounts will all make a difference. But the real change—allowing all US tourists to visit Cuba—is not authorized. That would bring in the big bucks. For example, some 900,000 Canadians visit Cuba each year, but currently only around 150,000 Americans do so under license. Some 500,000 from the diaspora community visit every year. The remittances and cash—perhaps over $5 billion a year, no one really knows—being brought into Cuba are a vital current lifeline for the Cuban economy.

For American business, the opportunities will be enormous, but the tense of the verb is still future. Cuba needs everything in products, services, and expertise. It has fantastic natural assets. But given current political ties, it is unlikely the Cuban government will approve a US company project, rather than a Venezuelan or Chinese [one]. However, many US products enjoy a big price advantage over the competition, so if Cubans were allowed by the US to be granted credit, trade could grow quickly.

Do you think Obama’s decision will be a net plus or minus, politically, for politicians who support it?

Cuba issues count for less and less in Florida and US national politics. Obama won Florida both times in 2008 and 2012 and almost got half the Cuban American vote in 2012. Younger Cuban Americans really want to reconnect with families and see the Cuba issue as one about economic conditions, not ideology or past vendettas. I think most politicians would want to put the Cuban issue behind them as a major factor in how people vote. But given the significant powers that certain individuals can wield in Congress—for example, to delay funding or appointments—this may be a forlorn hope.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.