Celebrating a Century of Performance Art

New show at BU Art Gallery explores genre’s history

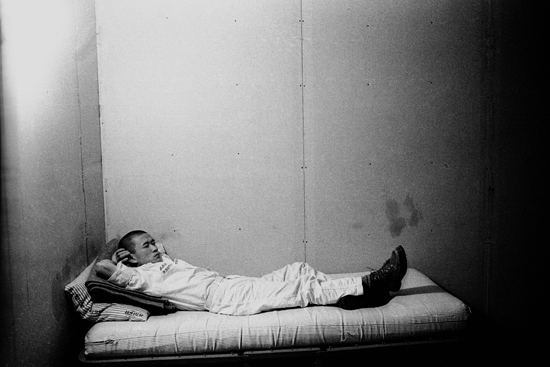

A photo of Tehching Hsieh’s yearlong performance piece, during which he locked himself in a small cell, is included in the BU Art Gallery’s new exhibition. Photo by Tehching Hsieh.

There’s something a bit ironic about 100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012), the Boston University Art Gallery’s new show examining the evolution of performance art over the last century. As Roselee Goldberg, one of the exhibition’s organizers, notes, “Performance art is the avant avant-garde.” Yet as the show makes clear, the cutting-edge, genre-bending art form has become so established that it now warrants a historical exhibition.

Over the past century, performance art, with its few strictures and its emphasis on experimentation, has easily managed to remain fresh. Artists of all stripes have been drawn to it: architects, dancers, sculptors, painters, actors. It can resemble opera, public sculpture, guerrilla theater, stand-up comedy, political protest, even a party. Two examples in the show demonstrate that stylistically, the form ranges widely, from the abstract, such as sculptor Dennis Oppenheim’s 1970 work in which he covers his hand with rocks, to the exceedingly visceral, such as William Pope L.’s 1996 performance piece during which he walked through Harlem wearing a 14-foot-long white phallus.

“Performance can be extreme, such as someone undressing in public while chewing shards of glass, or it can be a theatrical performance with song and dance,” says BUAG director Kate McNamara, who is currently teaching a College of Arts & Sciences art history class on the subject.

The unifying force behind all performance art is that the art is freed from being a mere object, that the creative act itself is the end product. Consequently, these works have a fleeting, transitory nature, unlike art that hangs in museums (think Yoko Ono’s 1965 piece in which she invited audience members at Carnegie Hall to cut her clothing off). That in-the-moment aspect has made performance art difficult to exhibit. Museums are usually left with only documentation of the performance: films, photos, and videos.

100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012) incorporates a wealth of these, such as photos of actress Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box in a gallery and a video of Christo’s monumental orange curtain hung across a mountain gap in Colorado. A video of Ono’s aforementioned performance is included. The list of artists represented in the show reads like a who’s who of performance art. A notable absence is the artist Karen Finley, who made the genre notorious and attracted the ire of conservative politicians in the 1990s with graphic performances in which she covered herself in chocolate, meant to symbolize feces, and recorded videos of herself painting canvases using her own breast milk.

In the BUAG show, six video monitors and scads of photos are organized along a timeline that runs around the gallery. The exhibition begins in 1909 with the Futurist Manifesto, a declaration by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti rejecting the past and embracing all the future had to bring, and ends in 2009 with photos of Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto bashing mirrors with a sledge hammer. The show requires a lot of reading and watching, so the gallery has added special benches for visitors to view the work.

As the exhibition’s subtitle implies, this is the fourth version of the show, which was organized by McNamara’s previous employer, MoMA P.S. 1, in Queens, N.Y. McNamara helped organize the show there and worked on subsequent installations in Moscow and Dusseldorf. Each incarnation has been slightly different, as curators at each venue add elements from their local performance art scene. Here, McNamara has recruited Boston-area performance artists, notably members of Mobius, the artist-run nonprofit established in 1977 to generate experimental art. Since its founding, the organization has produced hundreds of performances in Boston and around the world. Mobius will present a number of performances by various artists during the exhibition’s run.

McNamara has also included works by other area performance artists, among them Philip Fryer and Sandrine Schaefer, Dirk Adams, and John Gonzalez, who has transformed the gallery’s small annex into a trading post of sorts, where visitors can swap a personal belonging for one of the artist’s own.

Despite its long history, performance art remains little known to, or understood by, the general public. For the uninitiated, 100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012) is a thorough introduction.

100 Years (version #4 Boston, 2012) runs through March 25 at the Boston University Art Gallery, 855 Commonwealth Ave. The gallery is open Tuesday through Friday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday and Sunday, from 1 to 5 p.m. Admission is free. There is an opening reception tonight from 6 to 8 p.m.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.