Learning to Adapt

Peter Busher: Beavers, Beavers Everywhere Peter Busher: Beavers, Beavers Everywhere

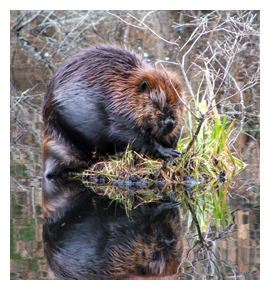

A century ago, there were virtually no beavers in Massachusetts. Farmers in the state had cleared beaver habitat for pasture and cropland, and the population of the North American beaver dwindled. Restoration campaigns during the last half of the 1900s and a decline in the fur market returned them to a near-original range, and today the beaver population seems to be growing exponentially. Between 1996 and 2001, the beaver population grew from 24,000 to nearly 70,000 animals. Beavers are beneficial for the environment because they dam streams, expanding the wetlands which in turn filter groundwater and provide habitat for other wildlife. But beavers can also be a nuisance to humans, damaging property, contaminating water supplies, and flooding roads and buildings.

Many people want to harvest beavers to control these threats, but biologist Peter Busher suggests a more passive approach. “My old advisor puts it this way,” he says. “Either you love beavers or you hate them, and that depends on whether they’re doing positive or negative things for you.” Busher says that the high numbers may not represent the true population across the state because beavers tend to live in small groups, making their population difficult to estimate. Also, the beaver population is dynamic; beaver families may try out one area but move on the next year if it turns out not to be suitable habitat. Dispersal of young adults also affects mating and rearing behavior. Two-year-old beavers leave the parent territory to find mates, so an extended period of migration can delay reproduction. Many people want to harvest beavers to control these threats, but biologist Peter Busher suggests a more passive approach. “My old advisor puts it this way,” he says. “Either you love beavers or you hate them, and that depends on whether they’re doing positive or negative things for you.” Busher says that the high numbers may not represent the true population across the state because beavers tend to live in small groups, making their population difficult to estimate. Also, the beaver population is dynamic; beaver families may try out one area but move on the next year if it turns out not to be suitable habitat. Dispersal of young adults also affects mating and rearing behavior. Two-year-old beavers leave the parent territory to find mates, so an extended period of migration can delay reproduction.

Busher adds that the high rate of increase seen in beaver populations, while alarming to residents whose trees have been cut or basements flooded, may not be a permanent trend. For years, Busher has been monitoring beaver populations on Prescott Peninsula, the strip of land between the east and west sections of Quabbin Reservoir that is off limits to visitors. After plotting the number of beavers on the peninsula over the past half-century, he noticed that the population grew exponentially at first, reached a brief plateau, and then fell to stabilize at 25% of its peak.

Many regions in the state are in the expansion phase, Busher explains, because they haven’t had beavers as long as the reservoir has. He says that although it seems like a big problem now, some of those areas are not suitable habitats for beavers and the animals will eventually move on. “The state is just lagging behind the peninsula,” Busher says. “We have studied how the natural population [in the absence of human impact] has grown and then decreased on the peninsula. This understanding can be applied to populations that are butting up against humans where conditions are less favorable for the beavers. If you give an area 25 years, it will stabilize at some lower level.”

The issue at hand, he explains, may be one of human tolerance. “It’s what wildlife people would call the ‘cultural carrying capacity’. How much will humans put up with?” There are so many benefits to tolerating the beavers, he says.

“We need to be more aware of our place in the whole ecosystem and learn to live with wildlife,” Busher says. If people can learn to live with beavers now, they will reap environmental benefits and the beaver problem will most likely take care of itself.

To read more about Busher’s research, visit www.bu.edu/cgs/faculty/inserts/busher.html.

For information on Quabbin Reservoir Fishery, www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/dfw_quabbin.htm.

For beavers in Massachusetts, www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/dfw_beaver_law.htm.

— by Leah Eisenstadt |

Peter Busher: Beavers, Beavers Everywhere

Peter Busher: Beavers, Beavers Everywhere  Many people want to harvest beavers to control these threats, but biologist Peter Busher suggests a more passive approach. “My old advisor puts it this way,” he says. “Either you love beavers or you hate them, and that depends on whether they’re doing positive or negative things for you.” Busher says that the high numbers may not represent the true population across the state because beavers tend to live in small groups, making their population difficult to estimate. Also, the beaver population is dynamic; beaver families may try out one area but move on the next year if it turns out not to be suitable habitat. Dispersal of young adults also affects mating and rearing behavior. Two-year-old beavers leave the parent territory to find mates, so an extended period of migration can delay reproduction.

Many people want to harvest beavers to control these threats, but biologist Peter Busher suggests a more passive approach. “My old advisor puts it this way,” he says. “Either you love beavers or you hate them, and that depends on whether they’re doing positive or negative things for you.” Busher says that the high numbers may not represent the true population across the state because beavers tend to live in small groups, making their population difficult to estimate. Also, the beaver population is dynamic; beaver families may try out one area but move on the next year if it turns out not to be suitable habitat. Dispersal of young adults also affects mating and rearing behavior. Two-year-old beavers leave the parent territory to find mates, so an extended period of migration can delay reproduction.