Millennials: A User Guide

You want to hire them, but do they want to work for you?

Associate Professor Jack McCarthy knows what you need to know about millennials.

He deals with classrooms full of them every day. In fact, you can trace a line from his undergraduate organizational behavior course to the challenges facing managers in just about every professional enterprise. McCarthy’s course, designed to elicit both self-reflection and thoughtful action among students in their late teens and early 20s, poses questions that drive every endeavor: How do I get people to perform their best when working in a group? How can we cultivate an environment where teams collaborate effectively? How can we demonstrate that our work together serves a larger purpose in the world?

By 2025, Millennials will make up 75% of the American workforce

Businesses are struggling to answer these questions. A 2013 Gallup report, State of the American Workplace, found that 70 percent of workers are “not engaged” or are “actively disengaged” from their workplaces, meaning they are not committed to making positive contributions to their organizations. Notably, Gallup found that younger millennials are the most likely to leave for a better job when given the chance, even when economic times are uncertain.

The millennial generation—typically, those born between 1980 and the mid-1990s—attracts a great deal of attention among researchers, marketers, and professionals in every industry. These are the young adults who are sitting in undergraduate and graduate school classes today. The 2014 Business Education Jam at Questrom, designed to identify ways to modernize the management curriculum, devoted an entire track to engaging millennials. The recent graduates among them have entered the job market, and employers have found that it pays to accommodate their working styles. Many in their late 20s and early 30s have risen to managerial positions and leadership roles. By 2025, they will make up 75 percent of the American workforce, and they already account for $1 trillion in US consumer spending.

Ignoring Millennials is not an option.

In addition to their tech savvy and comfort with multitasking, millennials have more experience than their elders working with peers from diverse backgrounds. And while they want to have autonomy in their pursuits, they expect to receive feedback, lots of it, about their progress. They want to make an impact—now. They don’t want to feel like they are wasting their time because there are so many other things they could be doing. They have high expectations for themselves, believing their efforts should matter and that the organizations for which they work should serve a greater purpose. And, by the way, they want time off to achieve a semblance of work-life balance.

And while the descriptions of a generation like the millennials are by definition imprecise—not everyone who came of age in the 1960s was a flower child—there are some useful lessons to share that can benefit every age group working today and those coming up next.

Millennial Relationship Management

McCarthy recalls hearing a colleague propose that a professor, concerned about students’ web surfing and texting in class, block internet access in the lecture hall.

“The suggestion was, why don’t we do it during the lectures because then they will pay attention more, and they won’t be able to do text messaging and check YouTube, and do all the things these crazy millennials are doing. And I was outraged at that suggestion,” says McCarthy, an associate professor of organizational behavior.

“We don’t want to stop them from doing what they are doing,” he says. “What we want to do is to deliver content in a way that enriches their learning experience. And if we are really interested in engaging them in discovery, then maybe the lectures we are delivering are too boring. Maybe it’s not all their problem.”

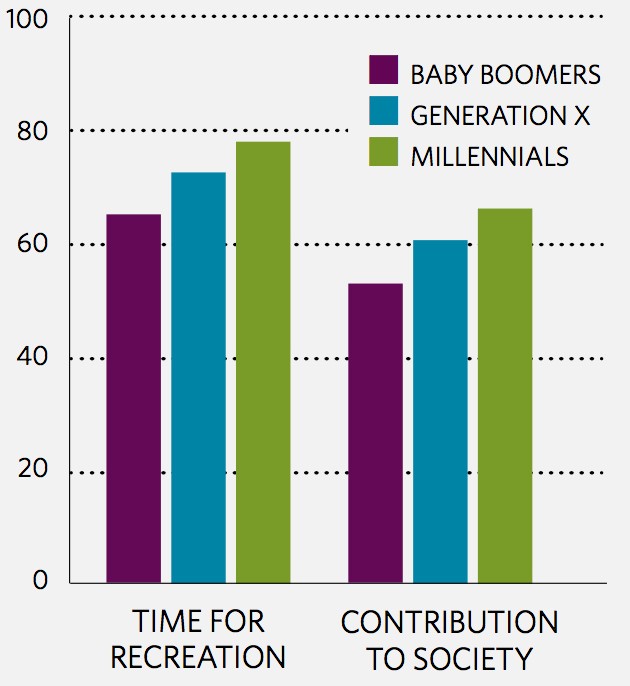

Percent Saying Life Goals Are “Quite or Extremely Important”

What McCarthy has learned in the pursuit of more engaging learning experiences applies to business, too. He says the current batch of undergraduates are skilled questioners, good debaters, and expert at connecting with people worldwide. “They have had Facebook friends around the world since they were nine years old. I’m interested in how we create environments for that generation to be excited about learning and the ways in which they push their own creativity and innovation,” he says.

Consequently, he says, many of his large lectures are gone. In their place are three-hour discussion classes in which students are responsible for their own learning. Students work in small teams to tackle challenges, research, and observe team dynamics. One scenario sends teams armed with a GPS device and clues to find items around Boston. Another assigns teams to interview six managers at one company about the challenges they face. And when class does meet in an auditorium, the material presented can take many forms: for example, discussions on group dynamics and leadership prompted by scenes from Shakespeare’s Henry V performed by theater students.

Millennials are not shy about questioning the relevance of these exercises, and McCarthy says he extolls their value for students’ careers. “They will say, ‘This is really interesting, but what does it have to do with me getting a better job?’ Then our job as faculty is to explain there are technical skills they will learn. And those technical skills are really valuable for the first job, the second job, or the third job out of college. But they are actually not that valuable for the fourth, fifth, or sixth job. What will set you apart is your ability to work with and through people,” McCarthy says.

This has always been true, McCarthy adds, whether people toted their iPad to high school or they recall flipping through a Rolodex. And while today’s business students crave knowledge about what it takes to succeed, McCarthy, who teaches executive leadership seminars, says the baby boomers also seek to understand how best to work with the millennial generation.

“Both groups of populations want the same thing,” he says. “The millennials are yearning to understand what it is to be a business man or woman, what it is to work in business, and [they] say, ‘Please teach me those secrets.’ And the baby boomers in their 50s and 60s, they are asking, ‘What are the millennials doing? What do they think? How do they work?’”

Attention: Millennials at Work

Rachel Reiser, assistant dean for the undergraduate program at Questrom, has been studying millennials since first hearing the label 14 years ago. Reiser’s efforts to better understand the students she was supporting as a college administrator led to her publishing a book in 2010 (Millennials on Board: The Impact of the Rising Generation on the Workplace) and founding a consultancy, Generationally Speaking, to help organizations develop strategies for employing millennials and deploying techniques for cross-generational collaboration.

Millennials are yearning to understand what it is to be a business man or woman, what it is to work in business, and [they] say, ‘Please teach me those secrets.’—Jack McCarthy

“One of the largest diversity issues in the workplace is across that generational issue,” she says. “There are different styles of communication, different points of view on how work should be conducted, and what employee engagement means.”

For example, consider a multigenerational group sitting at a conference room table during a work discussion. A baby boomer employee spots a millennial colleague swiping and poking at the phone in front of them. She thinks, He is not paying attention. I find that offensive. But the younger person could reasonably counter: How does she know I’m not looking up a salient point?

“Sometimes that is the case, and sometimes it’s not,” Reiser says of a smartphone user in this hypothetical situation. The point, she adds, is that getting the various demographic groups to collaborate effectively means cultivating cross-generational understanding, including a consensus of mutual expectations, so that baby boomers (born 1945 to 1964), generation Xers (born between 1965 and 1980), and millennials can understand each other’s working styles and how to accommodate them.

Reiser says she has found a number of useful techniques that enterprises can use to attract, retain, and engage millennials while encouraging cross-generational collaboration. Among them:

Reverse mentoring pairs a younger person with an older colleague to share knowledge about a topic, often technology-related. The arrangement, promoted by Jack Welch when he led General Electric, empowers the less-experienced employee, establishing her as a subject matter expert while opening an opportunity to cultivate a relationship with a more-established coworker. Millennials find this useful because “they want to make an immediate impact within the organization, and they can feel disappointed if they are not having the opportunity to do that,” Reiser says.

Corporate social responsibility programs that involve employee action demonstrate to millennials that companies are serving a broader purpose besides making a profit. Millennials are looking for their employers to make money but also to make a difference, a 2015 Deloitte survey found: 75 percent of millennials see businesses as too focused on their own goals and not paying enough attention to improving society.

These programs can also enable younger employees to take a leadership role from the start of a project. They can work with or lead others in developing the idea and plans for a community service project, and then implement it, Reiser says.

Feedback-rich environments with hands-on managers who engage millennials at frequent intervals. Reiser says that providing a structure in which new employees can perform pieces of a project and have frequent check-ins with a manager keeps them on task while providing opportunities to build expertise. This management style of leading through teaching helps retain them. “You have to be explicit about how you are working with them and why,” to answer questions about the purpose and payoff of this working style, Reiser says.

“Very Important” Job Characteristics Among High School Seniors

Workplace design that emphasizes open spaces—instead of cubicles and offices—and that supports employees’ mobile devices promotes collaboration. Spaces where workers can move when they want provide autonomy and flexibility and areas for small group discussions and team projects. Having leaders in open or glass offices communicates a sense of transparency as well as openness to questions and feedback.

Some companies, notably high tech giants like Google, provide meals and spaces for naps that make it seem like they cater to every conceivable need, cultivating a sense of belonging and encouraging employees to contribute their best. But even smaller firms creating light-filled spaces, exposing beams, and putting managers and employees in shared spaces are on the same page, Reiser says. They are working to build a sense of creativity and excitement. There is important work happening here and you want to be part of it.

And it’s not just startups or Silicon Valley tech firms. “Major, established companies are investing money and design effort and thought in to things like, ‘How do we look less finished, versus more?’ It’s all to create a space that engenders energy and an entrepreneurial mindset,” Reiser says.

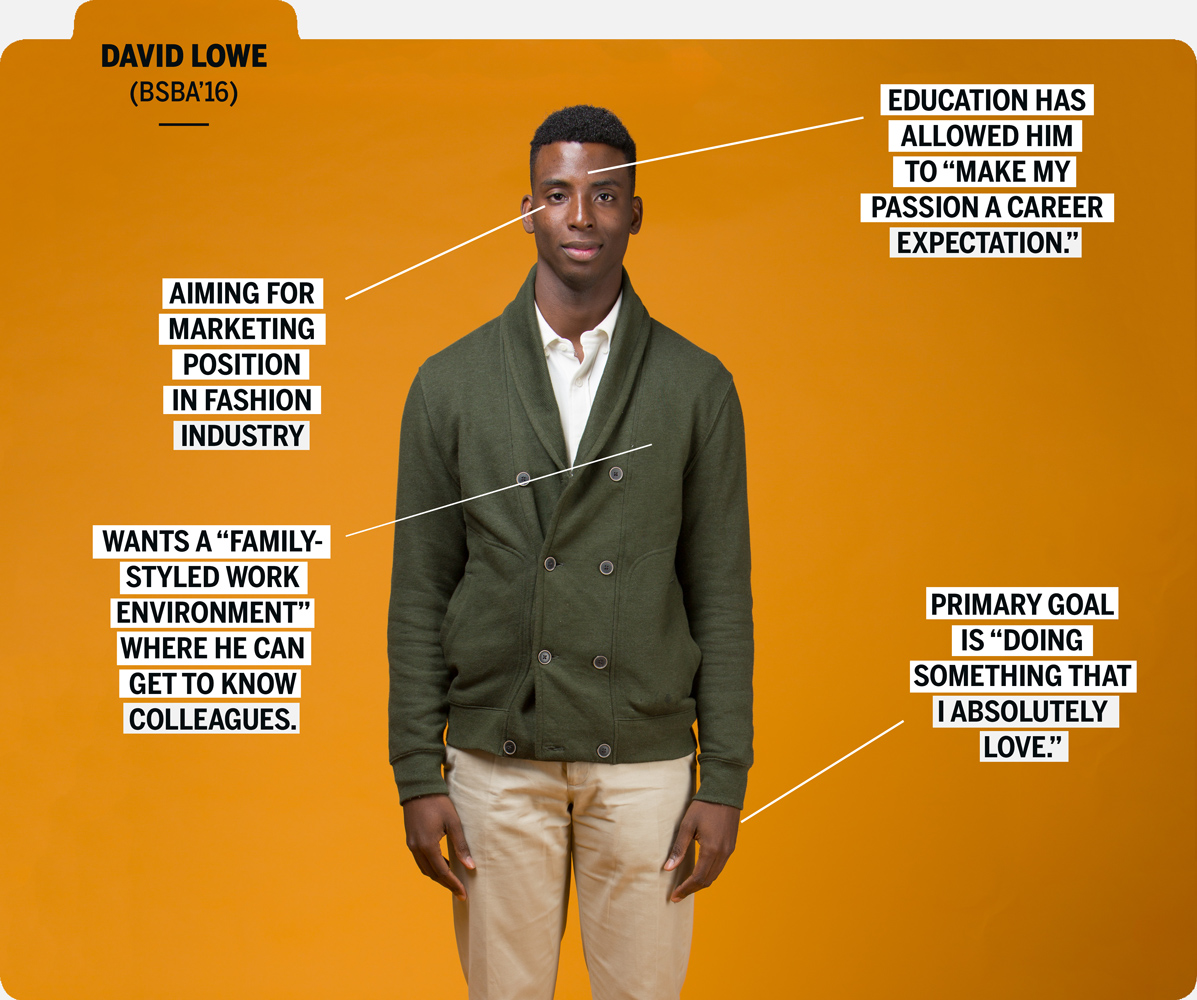

Fast Movers

When speaking about their first work experiences after college, four recent graduates interviewed for this article are forthcoming about their expectations and desires for the first chapter of their careers. All of them, it turns out, studied organizational behavior while at BU. Three of the four have moved on to their second employer within two years of graduation.

Anna Braet (BSBA’13) left a position at a health care consulting firm after two years to become an Education Pioneers Analyst Fellow working with Mass Insight Education, a nonprofit that partners with school systems. In her role, Braet helps teachers implement Advanced Placement programs. The chance to work directly with educators on programs drove her switch. But she did not do it lightly.

“I was worried when I did transition roles [that] someone could say, ‘She’s young and she will jump jobs.’ It’s an honest impression of millennials and sometimes it’s true,” she says. “I could have made my transition sooner, but I wanted to make sure I was making the decision for the right reasons, not just sort of jumping because I could.”

Kate French (CAS’15) and Brian Kimball (BSBA’14) also had good jobs after BU and chose to change with an eye toward graduate school as each addressed issues of work-life balance. French, who majored in psychology with a minor in business, says she left a great job at an advertising technology firm to pursue a graduate degree in psychology and gain field experience. She now works at a program for developmentally disabled adults.

The day shift at the disabled services agency means that she is not on call for advertising clients, answering their emails at night or on weekends. “I have really enjoyed having my downtime, making sure I carve out some time so I’m not always working or being on call 24-7,” French says. “This is a better feeling for me. It takes away a lot of the anxiety. And if I am working overtime, I get paid overtime.”

When he graduated from Questrom, Kimball joined a training program at a large financial services firm. “I liked the work I was doing,” he says, “but it didn’t fit what I was looking for. My personality, I realized, wasn’t a sales personality.” He left after four months and now works for BU School of Medicine as a grant administrator. “Same skills, different industry,” Kimball says of the analysis work involved.

And there was the issue of a balanced life. “I didn’t want to have the weight of work weighing on me. That was something I found in my first position; it was a little more of a blurred line. That wasn’t something I could know before I tried it,” he says.

Maggie Dunn (COM’15), who earned a bachelor’s in communications with a minor in business, says her job at FactSet, an information provider to the financial services industry, started with a training program, but will soon require her to lead client presentations and manage client relationships.

In addition to the early responsibility, she likes the 15 days of vacation time, the promise of a flexible work schedule, and the office perk of restaurant takeout four days a week. And she recently participated in a volunteer activity with colleagues, playing soccer and coaching a group of children in East Boston on a Friday afternoon.

“It’s a great job right out of school. Not many companies put that kind of trust in recent college grads,” to respond to clients’ questions for help, Dunn says, adding she feels she is making an impact already. “It’s a technology-based company, and we’re trying to keep up with a fast-paced world. Our clients are looking for the fastest way to do something, how do we make that a click away, how do we improve that.

“We, as millennials, can contribute to that,” she says.