98

ALICIA OSTRIKER

stage. Its realizations to date are both technically revolutionary and

poetically wonderful. Its future could possibly transform our under–

standing of the arts.

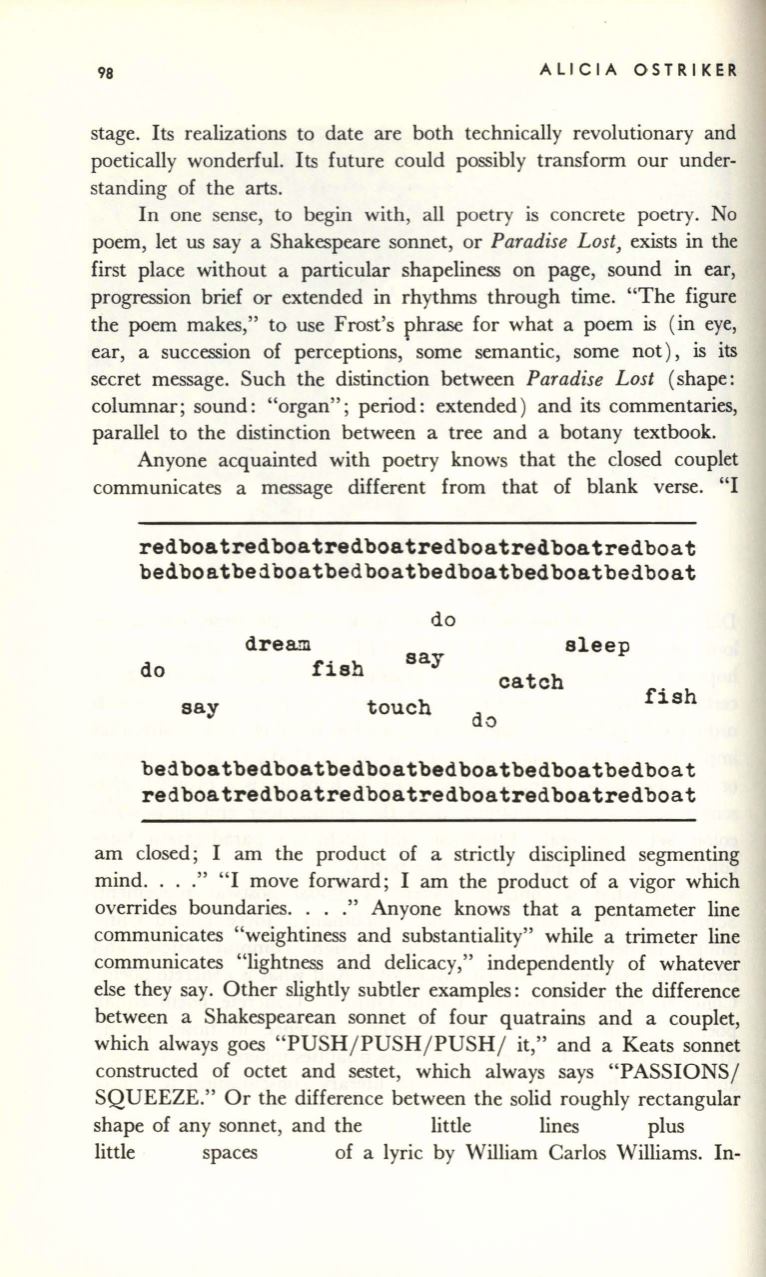

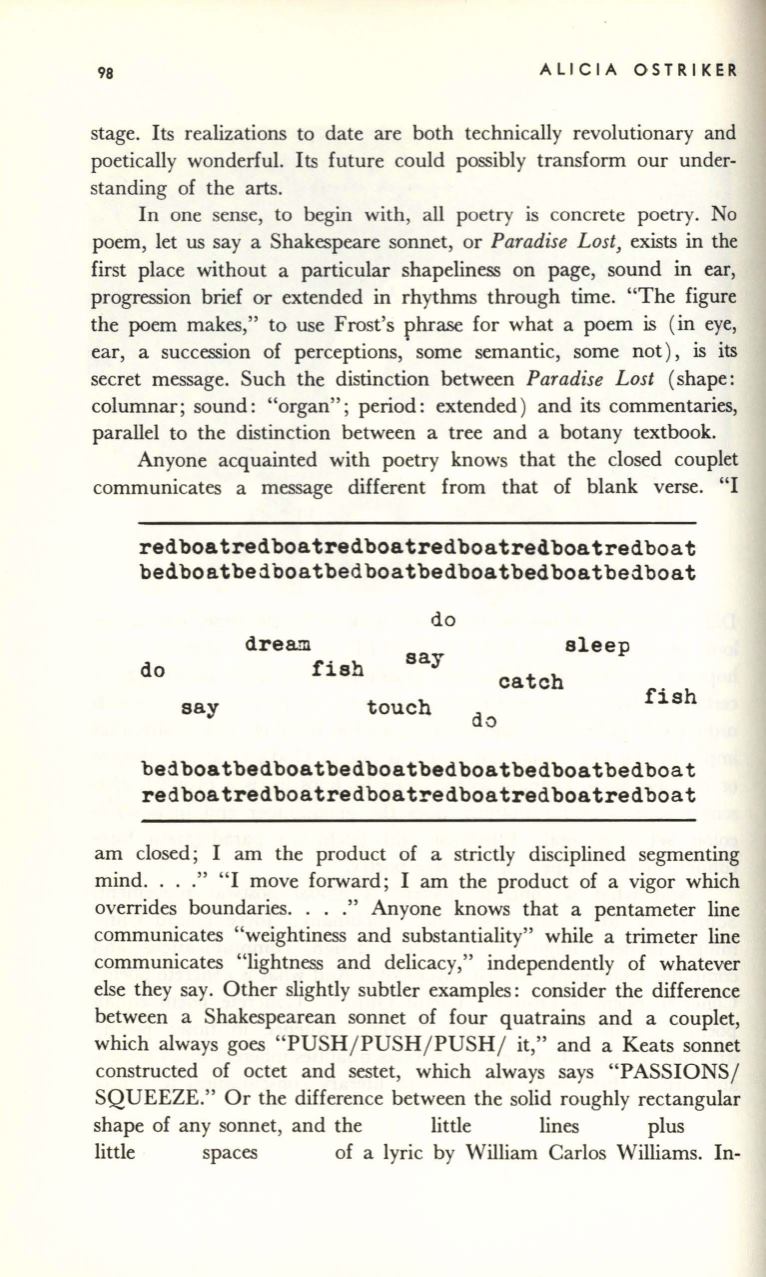

In one sense, to begin with, all poetry is concrete poetry. No

poem, let us say a Shakespeare sonnet, or

Paradise Lost,

exists in the

first place without a particular shapeliness on page, sound in ear,

progression brief or extended in rhythms through time. "The figure

the poem makes," to use Frost's phrase for what a poem is (in eye,

ear, a succession of perceptions, some semantic, some not), is its

secret message. Such the distinction between

Paradise Lost

(shape:

columnar; sound: "organ"; period: extended) and its commentaries,

parallel to the distinction between a tree and a botany textbook.

Anyone acquainted with poetry knows that the closed couplet

communicates a message different from that of blank verse. "I

redboatredboatredboatredboatredboatredboat

bedboatbedboatbedboatbedboatbedboatbedboat

do

do

dream

fish

say

touch

sleep

catch

fish

say

do

bedboatbedboatbedboatbedboatbedboatbedboat

redboatredboatredboatredboatredboatredboat

am closed; I am the product of a strictly disciplined segmenting

mind...." "I move forward; I am the product of a vigor which

overrides boundaries...." Anyone knows that a pentameter line

communicates "weightiness and substantiality" while a trimeter line

communicates "lightness and delicacy," independently of whatever

else they say. Other slightly subtler examples: consider the difference

between a Shakespearean sonnet of four quatrains and a couplet,

which always goes "PUSH/PUSH/PUSH/ it," and a Keats sonnet

constructed of octet and sestet, which always says "PASSIONS/

SQUEEZE." Or the difference between the solid roughly rectangular

shape of any sonnet, and the

little

lines

plus

little

spaces

of a lyric by William Carlos Williams. In-