PARTISAN REVIEW

103

anthology of concrete poetry. Within ten years, "after the concrete

'renaissance' in England, Germany, and Sweden during the early six–

ties, and the growing interest in the new poetry in such diverse set–

tings as Czechoslovakia, France, Spain, and the United States, the

poet Jonathan Williams could write, with apparent justification:

'If

there is such a thing as a worldwide movement in the art of poetry,

concrete is it.' " By this time a branch movement of semiotic or code

poetry had developed; some poets were writing poems as "scores

for electric sonorization"; others were writing "action poetry" which

utilized "living" material and tape recorder manipulations; still others

were making sculptural and architectural poems in materials ranging

from plexiglass to cast iron.

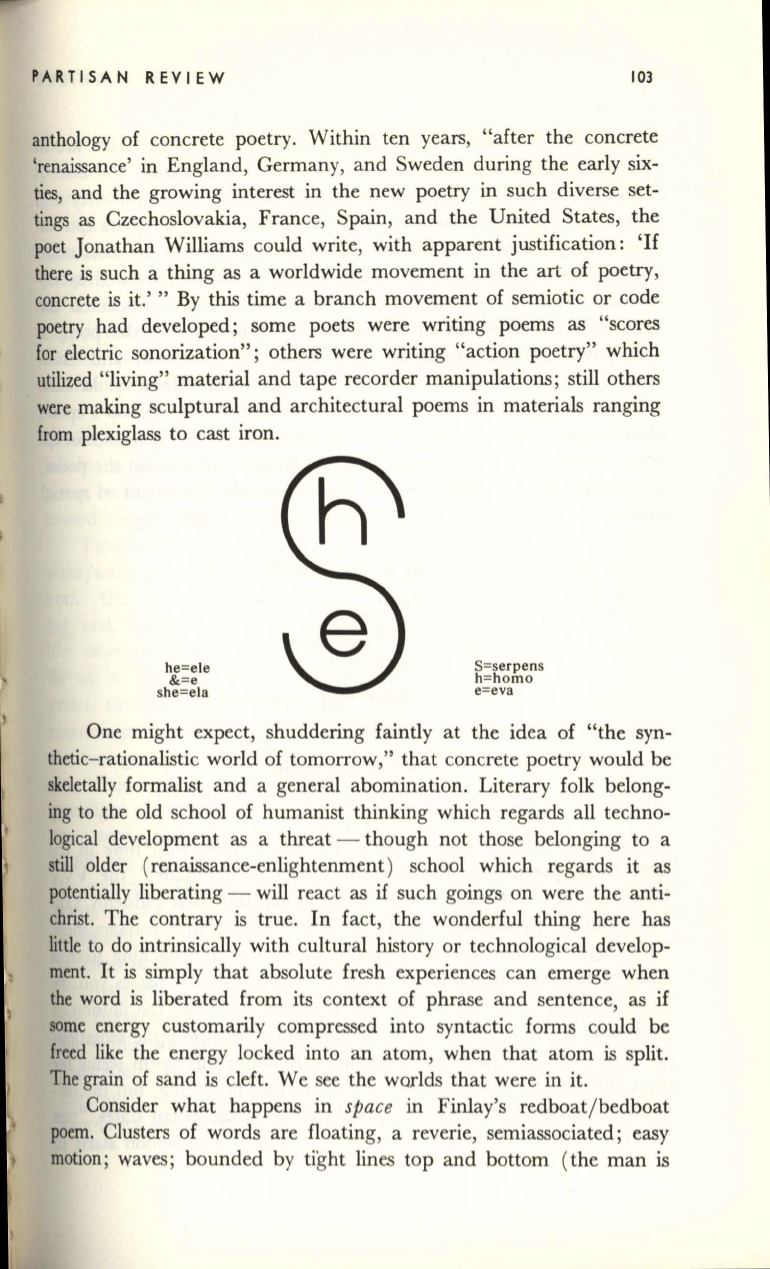

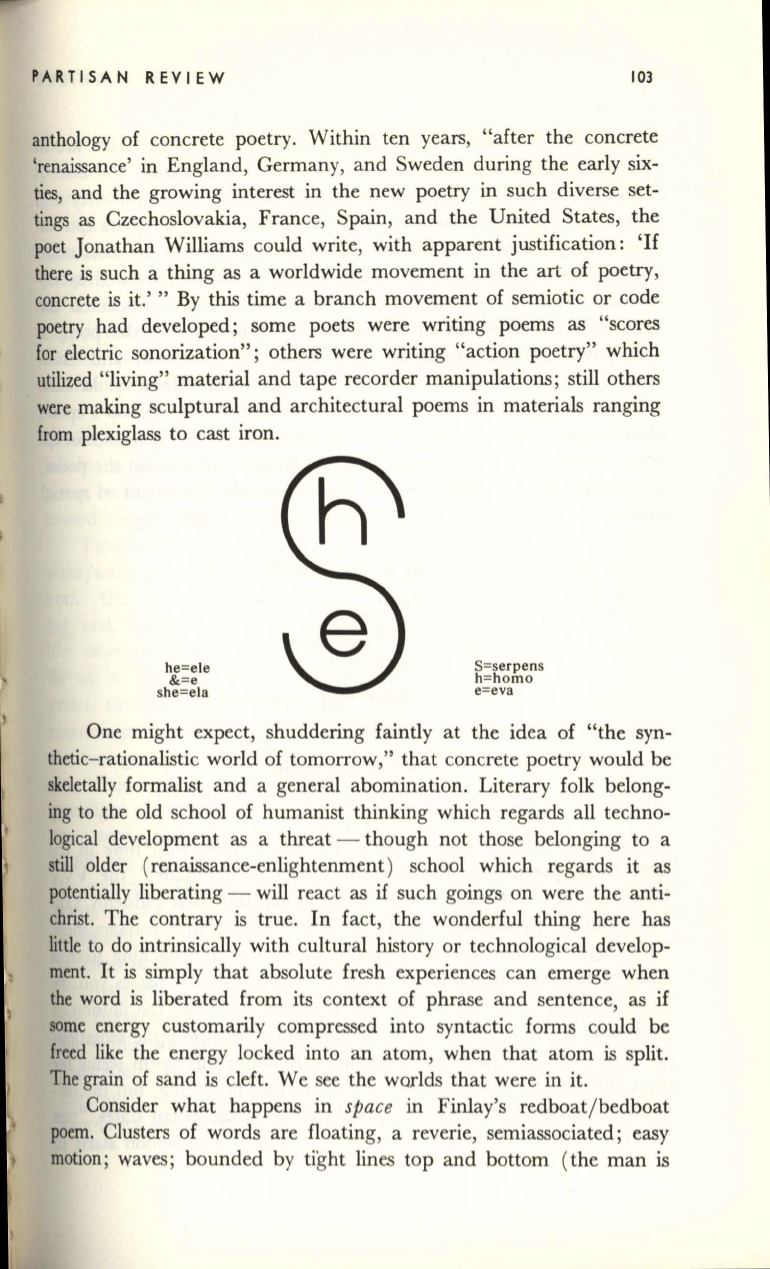

he=ele

&=e

she=ela

S=serpens

h=homo

e=eva

One might expect, shuddering faintly at the idea of "the syn–

thetic-rationalistic world of tomorrow," that concrete poetry would be

skeletally formalist and a general abomination. Literary folk belong–

ing to the old school of humanist thinking which regards all techno–

logical development as a threat - though not those belonging to a

still older (renaissance-enlightenment ) school which regards it as

potentially liberating - will react as if such goings on were the anti–

christ. The contrary is true. In fact, the wonderful thing here has

little to do intrinsically with cultural history or technological develop–

ment. It is simply that absolute fresh experiences can emerge when

the word is liberated from its context of phrase and sentence, as if

some energy customarily compressed into syntactic forms could be

freed like the energy locked into an atom, when that atom is split.

The grain of sand is

cleft.

We see the worlds that were in it.

Consider what happens in

space

in Finlay's redboat/ bedboat

poem. Clusters of words are floating , a reverie, semiassociated ; easy

motion; waves; bounded by tight lines top and bottom (the man is