Transforming Music Education Textbooks in South Korea: A Proposal to Mitigate Gender and Racial Discrimination

Nahyun Nadine Lim

Instructor’s Introduction

In WR 153, “Deception Across Disciplines,” students study ideas of deception across three disciplines in order to build a larger, student-determined capstone project. The scope of this project is led by each student’s respective interest in deception, a carefully selected genre, and the specific audience they wish to reach.

In our class, Nahyun explored deception across Art History, Data Science and Music Education before deciding to write within the discipline of Music Education and in the form of a music teacher’s guide for South Korean elementary school educators.

The culmination of Nahyun’s work, “Transforming Musical Education Textbooks in South Korea: A Proposal to Mitigate Gender and Racial Discrimination,” not only argues for an inclusive music curriculum that deepens students’ cultural awareness and builds empathy, but it also models the classroom instruction. What is remarkable about Nahyun’s project is how she delicately balances the need for such education with a guide on how to accomplish those objectives. She also stays keenly aware of her two audiences – the teachers who she wishes to convince of her argument and the students who will be swayed by the dynamic and visually appealing form of that instruction.

As a carefully considered text, Nahyun’s guide offers itself as a model of multi-modal writing that is acutely aware of the complexity of its audiences and the thoughtfulness in knowing how to reach them.

Anna Panszczyk

From the Writer

Growing up in South Korea, I have experienced the ambivalence of its culture—one that values tradition and national pride yet often resists inclusivity and diversity. This duality motivated me to explore how educational materials, particularly music textbooks, shape young students’ perceptions of race and gender. Music has long been a tool for socialization, and I believe that transforming its pedagogy can foster a more inclusive society.

Another key motivation for this project was my experience in CFA ME203: Introduction to Music Teaching and Learning with Dr. Sánchez-Gatt. The course deepened my understanding of how music education shapes students’ identities, social awareness, and emotional development. Through class discussions and research, I became more aware of the biases embedded in Korea’s music curricula and the need for equitable representation.

One of the main challenges in composing this project was finding comprehensive data on the representation of different cultures and genders in Korean music textbooks. Many existing studies focus on broader education policies rather than the specifics within music education. To overcome this, I analyzed widely used textbooks, cross-referenced my findings with research on inclusivity in education. By shedding light on these issues, I hope to contribute to meaningful changes in South Korea’s approach to music education.

Transforming Music Education Textbooks in South Korea: A Proposal to Mitigate Gender and Racial Discrimination

Racial and gender discrimination in South Korea

We have inherited many valuable practices from our ancestors during the Chosun Dynasty, including the principle of “age before beauty” and a spirit of perseverance that enabled the country to recover rapidly from invasions, conquests, and internal conflicts. Alongside valuable traditions, we have also inherited certain challenging legacies. Isolationist policies fostered racial biases, and periods of colonialism, nationalism, pure-blood ideology, anti-communism, developmentalism, and superiority discourses contributed to exclusionary social narratives. Additionally, Confucian principles instilled elements of male chauvinism that continue to impact societal structures today.

Racial Discrimination

South Korea has historically been a highly homogeneous society, where the concept of a single “Korean identity” has fostered national unity but also contributed to xenophobic and exclusionary attitudes. Immigrants, particularly from Southeast Asia and Africa, often face discrimination and social exclusion. This prejudice extends to the workplace, where foreign laborers experience poor working conditions and lower wages compared to native Koreans. In a survey conducted by the Korea Center for Immigrant Women’s Human Rights (2019), nearly 70% of immigrants reported having experienced discrimination due to their nationality or ethnic background. Furthermore, biracial Koreans, especially those with African or Southeast Asian backgrounds, are often targets of bullying and social exclusion. While media and entertainment increasingly feature biracial and multicultural figures, societal perceptions remain mixed. The emphasis on a uniform Korean identity sometimes leads to discrimination against individuals who do not “look Korean” or fit into traditional ideals.

Table 1.1: Multicultural Households in South Korea (2015-2021), Korea Women’s Development Institute, 2022.

| Year | Total Households | Multicultural Households | Percentage of Multicultural Households | Members in

Multicultural Households |

| 2015 | 19,560,603 | 299,241 | 1.5 | 887,804 |

| 2016 | 19,837,665 | 316,067 | 1.6 | 963,174 |

| 2017 | 20,167,922 | 318,917 | 1.6 | 963,801 |

| 2018 | 20,499,543 | 334,856 | 1.6 | 1,008,520 |

| 2019 | 20,891,348 | 353,803 | 1.7 | 1,062,423 |

| 2020 | 21,484,785 | 367,775 | 1.7 | 1,093,228 |

| 2021 | 22,022,753 | 385,219 | 1.7 | 1,119,267 |

Gender Discrimination

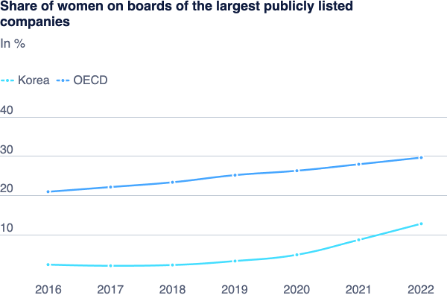

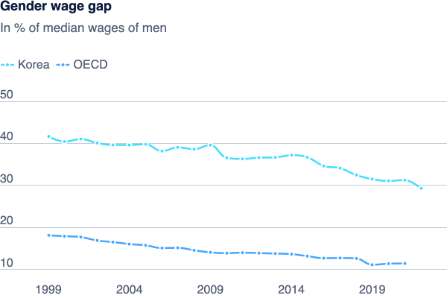

South Korea has a deeply rooted Confucian heritage, which emphasizes patriarchal family structures and traditional gender roles. This cultural background reinforces expectations for women to prioritize family obligations over professional ambitions. Despite legislative efforts on gender equality, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity and Work-Family Balance Assistance Act (남녀고용평등과 일·가정 양립 지원에 관한 법률), progress has been slow, and societal attitudes continue to influence career opportunities and expectations for women. Gender discrimination is another critical issue in South Korea. Women in the workforce face challenges, including wage gaps, glass ceilings, and limited opportunities for advancement. According to OECD data (N.D.), South Korea has one of the highest gender pay gaps among developed countries, with women earning significantly less than men for comparable work. The gender disparity is particularly pronounced in high-ranking positions, where women are underrepresented in executive roles across both the public and private sectors.

Figure 1.1: Share of Women on Boards of the Largest Publicly Listed Companies (2016-2022) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), N.D.)

Figure 1.2: Gender Wage Gap in South Korea (1999-2019), (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), N.D.)

Many countries are experiencing a significant shift in their population pyramids, marked by declining birth rates and an aging population, which poses serious challenges to sustaining economic growth and social stability. This demographic shift is particularly observable in South Korea, where the population is shrinking gradually, leading to a smaller workforce. To address this, it is crucial to adopt more inclusive attitudes toward gender and racial diversity in the labor force. Welcoming both foreign workers and actively supporting women’s participation in the workforce are essential strategies for mitigating the adverse effects of this population shift. According to research conducted in 2015 using a general equilibrium model capable of dynamic operations, the potential growth rates and total supply showed that the growth rate increased by up to 0.07 percentage points when immigrants made up 2% of the working-age population (Korea Economic Research Institute, 2015). When immigrants accounted for 5%, the increase was up to 0.17 percentage points, and when the share reached 10%, the increase was up to 0.33 percentage points. By embracing these changes, South Korea will better adapt to the realities of an aging society and ensure continued growth and vitality.

Figure 1.3: Population pyramid (1990). (Statistics Korea, N.D.)

The data before 1999 includes individuals aged 80 and above, while the data after 2000 includes individuals aged 100 and above.

Figure 1.4: Population pyramid (2024). (Statistics Korea, N.D.)

How Music Education Can Shape Students’ Societal Perspectives

For decades, experts have argued that music education supports elementary students’ learning by boosting critical thinking and emotional intelligence. Music’s distinct emotional resonance provides an outlet for students to explore, express, and regulate their emotions, cultivating greater self-awareness and social sensitivity (Ewell, 2020).

Beyond academic benefits, music education shapes students’ perspectives by promoting emotional, cognitive, and social growth. Engaging with music exposes students to a range of cultural expressions and historical backgrounds, deepening their understanding of the world. Learning songs from various traditions introduces students to different languages, customs, and viewpoints, which fosters empathy, respect for diversity, and an awareness of global interconnectedness (Gill, 2011). Music education also builds essential social skills such as teamwork, communication, and empathy. Participating in group activities—like choirs, ensembles, and collaborative music projects—encourages cooperation and a shared sense of purpose, reinforcing the value of listening to others and resolving conflicts constructively (UNESCO, 2023).

These insights underscore the need for inclusive music curricula. Ewell (2020) advocates for incorporating non-European musical traditions to address inherent biases in music theory education. Likewise, Mena (n.d.) highlights the importance of diverse representation in curricula to connect students from marginalized backgrounds with broader cultural perspectives. UNESCO’s report (Barbieri & Ferede, 2023) further supports inclusive content, suggesting that exposure to varied musical traditions can deepen students’ cultural awareness and empathy.

Improvement Plans for Music Textbooks in Response to Changes in Society

The necessity of providing education and information to combat racial discrimination is widely supported, as indicated by the following agreement rates among respondents: 86.3% agreed on the importance of content about the history, culture, and traditions of immigrants’ countries of origin; 87.3% supported including information on immigrants’ contributions to South Korea; 90.8% agreed on the need to promote respectful attitudes and cultural exchange with immigrants; and 85.3% saw the importance of educating about the harm caused by racist hate speech (Korea Center for Immigrant Women’s Human Rights, 2019). Based on these statistics, this paper suggests potential changes to the current music education textbooks, specifically referencing the Music Textbook for 3rd-4th Grade Elementary School Students published by MiraeN. Please note that this research was conducted using the 2015 edition of the textbook, as it was the latest version available online.

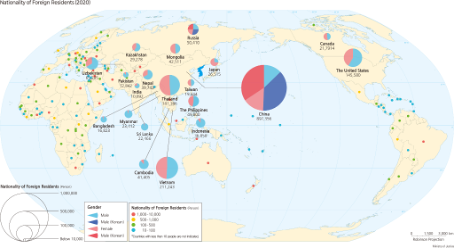

Diversifying the Origins of Music in Textbooks

We believe that music education can be a great way to foster cultural awareness and exchange between students from different backgrounds and create cultural acceptance among students. One key improvement we recommend is to include a broader representation of cultures within the music curriculum. The current music textbook includes 37 songs from various origins, as shown in the figure below. However, the distribution remains heavily weighted towards certain cultures, particularly Korean and Western countries. The songs’ origins in the current music textbook are predominantly Korean (57%) and European (22%), which does not reflect the diverse backgrounds of immigrants residing in Korea, primarily from East and Southeast Asian countries. This discrepancy underscores the need to update the curriculum to better represent modern Korean multicultural society. The Music Teaching Guide for Teachers, published alongside the textbook, reflects the government’s educational policy of preserving and promoting Korean music for future generations. While this focus is valuable, diversifying songs’ origins would offer students more opportunities to engage with and appreciate a broader range of cultural expressions.

Figure 3.1: Origins of Songs in Music Textbook for 3rd-4th Grade Elementary School Students (MiraeN, 2015)

Figure 3.2: Nationality of Foreign Residents (2020). (Statistics Korea, N.D)

Promoting Gender Equity in Group Work

The teacher’s guide includes numerous group activities but lacks attention to gender equity in these settings (MiraeN, 2015). Often, perceptions about gender can significantly influence students’ choices in “instrument selection, beliefs about creativity, leadership roles within groups, and rates of participation” (NafME, 2017). For instance, students may avoid choosing certain instruments or creative roles based on traditional gender stereotypes, limiting their engagement and hindering their development. Additionally, the guide suggests that teachers divide students by gender for certain activities, inadvertently reinforcing barriers between boys and girls rather than fostering collaboration and inclusivity (MiraeN, 2015, p.49). Increased awareness of how these perceptions of gender impact participation and create barriers in group settings could enable educators to approach group work in more equitable ways, ensuring that all students feel empowered to explore a variety of roles and participate fully. By actively addressing these biases, teachers can create a learning environment that promotes gender equity and allows students to thrive without limitations imposed by stereotypes.

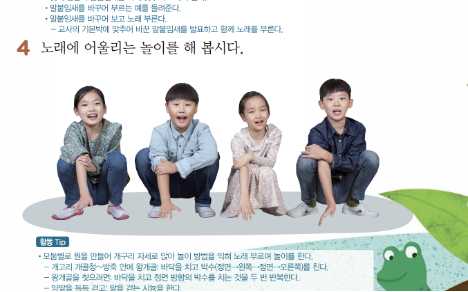

Broadening Racial, Cultural, and Gender Representation in Materials

In addition to diversifying the origins of songs, it is essential to broaden the representation of races, cultural backgrounds, and genders among the figures, pictures, and illustrations featured in the music textbook. Currently, all photographs of students included in the textbook depict Korean students and nearly all musicians represented are European men, limiting students’ exposure to diverse cultural, racial, and gender identities. Furthermore, most characters in the textbook are portrayed with similar skin tones, which does not reflect the multicultural society that Korea is becoming. Including students and musicians from various ethnic backgrounds, as well as featuring more women musicians, would foster a more inclusive and culturally aware learning environment. Such representation would allow students to become familiar with a broader spectrum of cultures, people, and gender roles, ultimately promoting empathy, respect for diversity, and an understanding of global interconnectedness from a young age.

Figure 3.3: Sample representation of a foreign musician in Music Textbook for 3rd-4th Grade Elementary School Students (MiraeN, 2015).

Figure 3.4: Sample representation of students in Music Textbook for 3rd-4th Grade Elementary School Students (MiraeN, 2015).

Sample Textbook Suggestion

Conclusion

The history of our music education began during one of the darkest periods in our past—when our country was divided in two—and has continued to influence our nation throughout other significant moments in our history. The first music curriculum, published in 1955 after the Korean War, aimed to address ideological conflicts within post-war society and to instill values of “patriotism, nationalism, and citizenship in students” (Choi, 2007). Later, during the military dictatorship period from 1960 to 1980, music education was strategically used to promote nationalism and patriotism, aiming to protect the public from foreign influences. As desires for social status, individualism, and materialism, influenced by foreign countries, became more widespread, these values prevented dictators from exerting control over the people, and music education was exploited to promote opposing values. Whether exploited or properly used, music education has been a powerful tool for shaping society.

Now, we are facing another shift in our society, where individuals increasingly believe in their right to voice opinions and question the authority granted to certain groups. The world is becoming rapidly globalized, increasing interactions with foreigners, whom we still largely view as subordinate to our nation. Regardless of the predominant contradiction, many statistics suggest that we will have to accept more immigrants in the future to prevent our country from disappearing. Starting with music education, let us take action to shape our growing population’s vision of the future and build a more inclusive society. By embedding themes of equality and cultural understanding, we can use music education to dismantle ingrained biases and foster empathy from a young age. We have the power to prepare future generations to embrace diversity, challenge discriminatory norms, and actively create a harmonious, equitable, and sustainable society. Now is the time to act and commit to a music curriculum that shapes individuals and the foundation of our nation’s values.

Bibliography

Jung, S. M., et al. (2022). Gender statistics in Korea. Korean Women’s Development Institute.

https://gsis.kwdi.re.kr/gsis/upload/file/202309244_12695100000.pdf

Kim, J. H., et al. (2019, October). 한국사회의 인종차별 실태와 인종차별 철폐를 위한

법제화 연구 [A Study on the State of Racial Discrimination in Korean Society and Legislative Efforts for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination]. 한국이주여성인권센터 [Korea Center for Immigrant Women’s Human Rights]. https://gsis.kwdi.re.kr/gsis/upload/file/202309244_12695100000.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (n.d.). Gender Dashboard on

Gender Gaps. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). https://www.oecd.org/en/data/dashboards/gender-dashboard.html?oecdcontrol-74aaf2d9f6-var1=KOR

Korea Economic Research Institute. (2015, January 5). 이민 확대의 필요성과 경제적 효과

[The economic impact of immigration on South Korea: A general equilibrium analysis]. Korea Economic Research Institute. https://www.keri.org/keri-insights/979

Statistics Korea. (n.d.). Population pyramid. Statistics Korea.

https://sgis.kostat.go.kr/jsp/pyramid/pyramid1.jsp

TEDx Sydney. (2011, November 4). TEDxSydney – Richard Gill – The Value of Music

Education [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HeRus3NVbwE

Barbieri, C. & Ferede, M.K. (2023, September 18). A future we can all live with: How education

can address and eradicate racism. UNESCO, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/future-we-can-all-live-how-education-can-address-and-eradicate-racism#

Ewell, P. A. (2020). Music theory and the white racial frame. Music Theory Online, 26 (2).

https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.2/mto.20.26.2.ewell.html

Mena, C. R. (n.d.). Accessing the inside of the tent: The optics of inclusivity in music education.

Statistics Korea. (n.d.). Nationality of Foreign Residents (2020). Statistics Korea.

http://nationalatlas.ngii.go.kr/pages/page_2683.php

National Association for Music Education. (2017, December 21). Embracing Human Difference

in Music Education. NAfME. https://nafme.org/blog/embracing-human-difference-in-music-education/

Choi, M.Y. (2007). The history of Korean school music education. International Journal of Music

Education, 25(2), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761407079952

Nahyun Lim is a junior at Boston University majoring in Biomedical Engineering with concentrations in Machine Learning and Technology Innovation. Originally from South Korea, she moved to the U.S. for college. She is passionate about advancing precision medicine and making science education accessible to underrepresented students. She would like to thank Dr. Anna Panszczyk for encouraging her growth as a writer and providing the opportunity to explore topics beyond engineering as a non-native English speaker, as well as Dr. Sánchez-Gatt for deepening her understanding of music education and its role in shaping social awareness.