Chasing After Time: Examining Mirrors and Windows in Serial Photography

Mrinalee Reddy

Instructor’s Introduction

In WR152: Family Snaps and Stories students learn to research and conceptualize family subjects in photographic portraiture. For her research paper project, Mrinalee Reddy wanted to compare different approaches to serial photography, which is the taking of a photograph yearly in the same manner with the same sitters. The artist most famous for serial photographs is Nicholas Nixon, whose Brown Sisters series has become iconic for documenting the effects of time on his wife and her three sisters. What makes Reddy’s essay “Chasing After Time: Examining Mirrors and Windows in Serial Photography” so compelling is her discovery of Annie Wang’s serialized portraits of herself with her son from the time she was pregnant with him to the present. Wang’s embedding of the earliest portraits within the most recent one not only contrasts Nixon’s sequential approach to the Brown sisters stylistically but also elicits different effects in the viewer. Mrina wanted to understand this difference and found a framework in John Szarkowski’s concept of photography as either a medium of objective exploration (window) or subjective expression (mirror). Mrina found that Szarkowski’s metaphors allowed her to differentiate each photographer’s approach to time and family. Mrina realized that while Nixon and Wang both portray women aging over the years, Wang reckons with her experiences as a working mother, whose son grows from infant to young adult before our eyes.

As a resource for teaching, the essay models how theory can offer a framework for interpreting art in different ways. Mrina’s sharp visual analysis is integrated with argument sources, such as critical reviews and artist’s statements. Mrina wrote a long and thorough draft, which she worked hard to revise and clarify with her peer reviewer and me. It was a joy to see Mrina’s ideas develop boldly on the page and to learn about Annie Wang’s innovative, and wryly funny, photography.

Michele Martinez

From the Writer

Humans are obsessed with time. We want to trap it, tame it, bottle it, stopper it, and save it up for a rainy day when we ultimately find ourselves at the mercy of the clock once again. Serial photography understands the unchanging, universal truth of time passing, and tries to change our perception of it. From something that needles and saddens us, to something of beauty, no matter how inevitable it is. Photography links everything together as moments in time. You are the person looking at the photograph, and you are the person in the photograph too, reaching forward through the seas of time to touch your future self. The image mirrors you, but simultaneously is a window into the past. In this essay, I examine these unique mirror and window properties of iconic serial photography series like The Brown Sisters and Mother as a Creator. I also hope to make the distinction that serial photography is not just a function of time, but a search for identity in an ever-changing world.

Chasing After Time: Examining Mirrors and Windows in Serial Photography

I, like many others, own a family photo album. Every so often, I pick it up, flip through its crinkled pages, and marvel at how much we have changed, at how much time has passed since we clicked the shutter button. Some years are filled with my consistent gap-toothed smile, while others are sparsely recorded, jumping between wildly different images (How many preteen girls enjoy having photos taken of themselves? Not me for sure), and some are completely unrecognizable. Family albums like these are casual practices in serial group imagery. Taken with sequential intent and with rigorous control of the elements within the composition, this genre of photography functions almost like a flip book, creating a sweeping look through the lives of its subjects. The popularity, indeed, the virality, of serial imagery cannot be understated. For instance, many of us might have come across new videos going viral of someone having “a photo taken every year since birth.” Clearly, something about this style of photography compels us, speaking to the human condition that is marked by the fleetingness of life, and the tenuous connections formed with each other. One of the pioneers in this field is Nicholas Nixon, with his series The Brown Sisters spanning over 4 decades (1975–current). Another innovative style of serial photography is displayed in Annie Wang’s seminal series Mother as a Creator (2001–current), which, incidentally, also went viral a few years ago. Her poignant self-portraits of the growth of a single mother and her son is a unique take on the genre. Why does the focus on maturation compel us? And what features of the genre aid in this emotional confrontation? While Nixon’s photographs are a classic example of a window in serial family portraiture, I will look at how Wang inverts the notions of the genre to create a mirror using an autobiographical, mise-en-abyme approach.

Photography and time are inseparably bound. Vernacular photographs are often taken to “freeze” a moment of time, and remember a transient, passing moment for eternity. This is especially true for family photographs because of their ability to capture records for future generations. Still, their dimensionality is often questioned. How much of a person, who is incredibly rich in unique characteristics and personality, can really be conveyed through a still image? Alfred Stieglitz argues that it is impossible to expect a single photograph to “be a complete portrait of any person” (qtd. by Gurshtein). People constantly evolve over their lifetimes and an image that is accurate right now may not be a year from now. Thus, the genre of serial photography arose as the process of photographing the same subject multiple times across varying timespans to investigate change, time, and identity. It is intimate, yet obscure; constantly changing, yet consistent, wholly multidimensional. For instance, by looking at serial photography, “the observer actively combines two visions: the one the past casts on the present […] and the one the present casts on the past” (Valadie 14). So how do we understand the depth that these images create, both standing alone and within the greater series? One way to examine serial photography could be through John Szarkowski’s Mirror and Windows theory. Szarkowski believed that to understand photography, one must consider “the photographer’s definition of his function” (Szarkowski 11). To him, photographs exist on this continuum between mirrors (a subjective romantic expression of the artist themselves) and windows (an objective exploration of the external world). We can use this lens to interpret Nixon’s and Wang’s group photo series.

The Brown Sisters is arguably the most infamous example of this oeuvre and set a precedent for the variations to follow. The backstory is as follows: every year since 1975, Nicholas Nixon, a photographer from Massachusetts, takes a photograph of his wife Bebe Nixon (nee Brown) and her three sisters. The Brown Sisters, Truro, Massachusetts is an image from the year 1984, close to a decade into the project. To transverse through the series of images, a certain framework of familiarity arises that keeps you grounded as the years fly past you. All the photographs are 8 x 10” black-and-white negatives, almost always taken outdoors in a grid, and the sisters are always standing in the same order, from left to right: Heather, Mimi, Bebe, and Laurie. Beyond their aging faces and shifting bodies, an emotional growth can be detected over time. In the 1984 image, they stand windswept on a beach with their arms hugging their bodies into a tighter circle, but just a few images ago, in the 1975 image, they stood aloof and brazen, almost awkward in the camera’s gaze. Serial photography unlocks nuances and dramas that viewers are often eager to question and create narratives around. Comparing and contrasting the various images, which are often shown in horizontal chronological order, exemplifies how “the camera records the differences and similarities of individual subjects” (Grundberg) better in a series, creating greater depth and value.

Echoing Szarkowski’s terminology, this series, which seems so sequestered from the historical timeline outside the sisters, actually lets the world back in. This is why we are drawn to The Brown Sisters: because we see ourselves in them. The candidness of their posing, their unassuming clothing, and the sincerity of their sisterly bond create a sense of familiarity and comfort. Implicitly, we also know Nixon is aging behind the camera too and that the series cannot continue forever. Their story is reflected in our own lives and provokes introspection. “What is evident…” Elaine King writes of the series, “…is an emphasis on the cycle of life” (King 72). Looming in the distance of everyone’s future is the harsh truth of mortality; Nixon just helps to ease us into acceptance.

Despite being photographed in locations across America, Nixon maintains smooth continuity, to the point that one often forgets that a fifth person figures into this equation. The focus is on the sisters, in a documentary-style approach that was praised by Szarkowski. Yet at some moments, the veil is briefly lifted. In The Brown Sisters, Truro, Massachusetts, on a sandy beach in Truro, Nixon’s shadow falls over the subjects, reminding us of his presence and role as a memory keeper. One has to assume that his perception and gaze influence the way we view these images. Nixon has a “formal, somewhat detached” (King 67) approach which points at his position as an outsider to the sisterly relationship portrayed through his lens. His objective view casts over the subjective lives of his subjects. This provides an alternative perspective of the series’ greatest strengths. These images are windows into the lives of the Brown sisters, who act as “a parallel to the lives of many women” (Brown 4). This makes them relatable, but simultaneously impersonal. Any nuance we might uncover is all conjecture, carefully mined from locations, dates, clothing, etc. We understand the universal process of aging and mortality through these subjects and thus “better know the world” (Szarkowski 25), but their rich history is hidden and left out from the photographic transaction, and so is Nixon’s.

In a direct contrast to the Brown sisters, who “rely on Nixon as the producer, director and creator to release their image” (King 75), Annie Wang takes things into her own hands. A Taiwanese photographer, she began her series Mother as a Creator (2001–current) when she was a graduate student for her dissertation and heavily pregnant with her son. Every year, give or take, she clicks a photograph with him, documenting his childhood, but also their shared growth over the years. Like Nixon’s images of the Brown sisters, the images in the Creator series are sequential black-and-white portraits, consistently framed, exploring the “accumulation and extension” (Wang 206) of time. However, Wang ingeniously creates a “time-tunnel” (Wang 206) sequence by displaying the previous years’ portraits on the wall behind her. Re-photographing her self-portraits creates a visual journey for the viewer in all directions, from one photograph to the next, and within each photograph itself, an infinite vortex that dives deep into the past. This effect is a type of mise-en-abyme, the duplication of a photo in a photo and “an internal mirror reflecting the totality of the work that contains it” (Owens 76). There is an implicit connection between this style and the “mirror” of Szarkowski’s theory. Mise-en-abyme simply allows for a rawer play between time and identity, an “indefinite […] substitution, repetition, and splitting of self” (Owens 77). Mother as a Creator is a clear reflection of the “portrait of the artist who made it” (Szarkowski 25), both literally and metaphorically, thus cementing it as a “mirror.” Wang places herself squarely in the frame with her son, their history, and material belongings, painting the story of the messy, real life of the photographer.

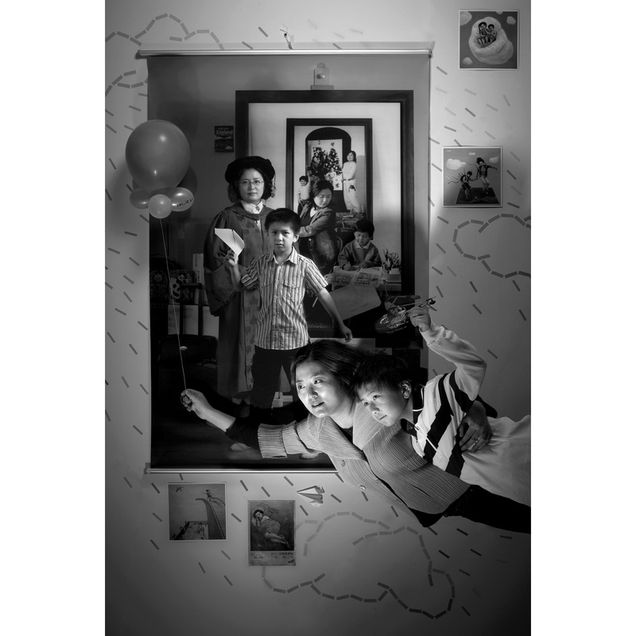

The recursive effect created through the re-photographic approach allows for a richness of depth that hits you as you view these images. It can be a bit dizzying sometimes. She and her son are loosely posed, and each photograph has its own creative set reflecting significant moments and stages in their lives together. For instance, Fig. 1, aptly titled Celebrating Christmas, features Wang seated with her son on a tricycle next to her in front of a Christmas tree. Wang holds a box that features her dissertation artwork, and a droll tree stands behind them decorated with DIY ornaments the two created together. It is personal and intimate, and it tells us about them. Despite being the fourth image in the sequence, it is already busy with details. Still, the first image of a pregnant Wang is visible in this photograph, before the layers get piled on too much to see it (the series is still ongoing). I feel that the tunnel of portraits acts as a family member in its own right within the picture. It has its own character, and its large size blocks out the otherwise empty space that would be seen in photos of single families. It is part of their little unit, bringing them closer to one another. In Fig. 2, the two fly through a faux thunderstorm, reflecting the tough times they faced that year, with the portrait tunnel sheltering and looking over them. The deep intimacy her photographs emanate speaks to the mother-son bond the two have in this non-traditional family structure. This is because Wang is “totally in control as producer, creator, and actor” (King 75) in her photographs. This series is ultimately centered around her story, life, and family and thus, she can portray a deeper range of emotions and more accurate depictions of the relationship with her son than an outsider could.

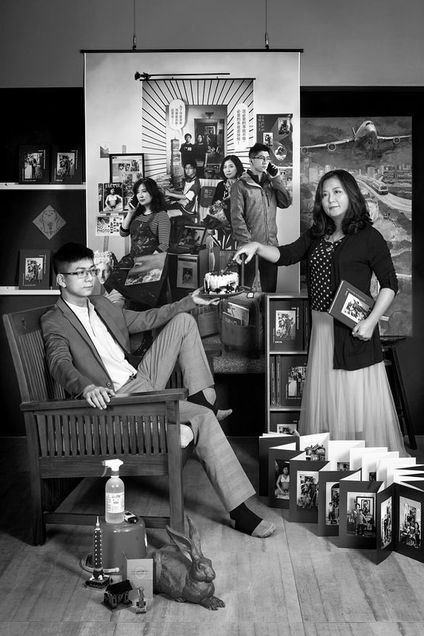

The series unfolds beautifully with each passing year as photographic layers continue to be added. As we flash through the years before, we watch her son grow from an unborn baby to an adult leaving for college. We also see Wang’s growth, not only marked by time and aging, but with props that speak to her accomplishments and ventures. In Fig. 3, we see the latest installment in the series, from 2022. It commemorates Wang’s 50th birthday, and she is surrounded by copies of her newly published book which includes the Mother as a Creator series. There is an interplay with the world outside the photograph—the impact of this series has made its way back into the narrative. This contrasts The Brown Sisters, who are detached and mysterious. These images are abundant with details about their life. We see Wang graduate, move houses, hold exhibitions, get featured in magazines, and more. It is warm, relatable, and touching, despite being very specific to the pair. The images do not only record maturation over time but explore different issues that Wang felt strongly about. She reflects on a question that inspired this series; “I love children, but why am I so afraid of becoming a mother?” (Wang, “Reframing Motherhood for 20 Years.”) This series, as expressed in its title, examines the difficulties single mothers face in her society, especially when attempting to carve out a career for themselves separate from their role as a caregiver. Wang is an artist, and she holds onto that fiercely throughout motherhood, which is expressed poignantly through her self-portraits with her son, both of which are her dear creations. Thus, she uses the time sequencing of photographs to explore motherhood and its fragile balance with art and the struggle to find time to do both.

In conclusion, whether a mirror or a window, both series are stunning explorations into time, familial bonds, and the effervescence of life using the medium of serial photography. We find comfort in these images because they give us familiarity and a sense of solidarity. We are not alone in wanting time to stop on its incessant march, but we need to find beauty in its inevitability. As Wang puts it, her photographs “allowed me to counter the negative impacts of time and to turn them into positives” (Wang 213). While Nixon’s mosaic of images creates a moving, expansive work when viewed in its entirety, Wang elevates these goals further using mise-en-abyme. Her autobiographical approach creates greater dimensionality; we are seeing her life through her eyes and vision. Thus, serial photography forces us to reckon with our identity and how we choose to spend our time alive, which is particularly touching in our fast-paced world.

Works Cited

Brown, Peter. “Review of The Brown Sisters.” Spot, Spring 2000, https://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/503774/5883178/1266974520853/brown-sisters.

Gurshtein, Ksenya. “The Serial Portrait: Photography and Identity in the Last One Hundred Years.” National Gallery of Art, 2012, www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/exhibitions/pdfs/serial.pdf.

Grundberg, Andy. “Nicholas Nixon: The Brown Sisters.” Aperture, 2006, https://issues.aperture.org/article/2006/2/2/nicholas-nixon-the-brown-sisters.

King, Elaine A. “Black & White: Two portrait stories.” The Journal of American Culture, vol. 31, no. 1, 2008, pp. 66–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734x.2008.00664.x.

Nixon, Nicholas. The Brown Sisters, Truro, Massachusetts. 1984. Gelatin silver print. The Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/54152.

Owens, Craig. “Photography ‘En Abyme.’” October, vol. 5, 1978, pp. 73–88. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/778646.

Szarkowski, John. Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960. The Museum of Modern Art, 1978.

Valadié, Flora. “Serial Production, Serial Photography, and the Writing of History in Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance.” Transatlantica vol. 2, 2009, https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.4642.

Wang, Hsiao-Ching. “Sustaining the creative identity of a Taiwanese artist during motherhood: a sequence of six artworks within an installation.” Diss. University of Brighton, 2009. https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/4756989/Binder1_Redacted.pdf.

Wang, Annie Hsiao-ching. “Reframing Motherhood for 20 Years.” Translated by Brandon Yen. Taiwan Panorama, 2021. http://www.taiwan-panorama.com/en/Articles/Details?Guid=1b800912-0c05-4fcd-979f-1118492a3226.

Wang, Annie Hsiao-Ching. Celebrating Christmas. 2004. Black and White Photograph. Artanniewang, https://artanniewang.weebly.com/the-mother-as-a-creator.html.

Wang, Annie Hsiao-Ching. Making dreams, 2011. Black and White Photograph. Artanniewang, https://artanniewang.weebly.com/the-mother-as-a-creator.html.

Wang, Annie Hsiao-Ching. Happy 50th Birthday, 2022, Black and White Photograph. Artanniewang, https://artanniewang.weebly.com/the-mother-as-a-creator.

Mrinalee Reddy is a sophomore from Chennai, India, currently pursuing Psychology and Environmental Science in the College of Arts and Sciences at Boston University. Growing up, she poured over stacks of her grandparents’ photo albums, and now reverently carries her mother’s tiny digital camera wherever she goes, hoping to create similar archives of her own. She took WR152: Family Snaps and Stories with Professor Martinez in fall 2023, and grew to appreciate the deeply intimate medium of photography even more. She is very grateful to Professor Martinez for her encouragement, as well as her strong interest and confidence in her writing.