The Rest Is Poetry

Two CAS professors' literary discoveries go beyond fine phrases.

by Annie laurie Sanchez

Few experiences induce gooseflesh like the unexpected discovery of an old manuscript, a physical connection with someone long gone. But such treasures often hold much more, as two College of Arts & Sciences professors recently found.

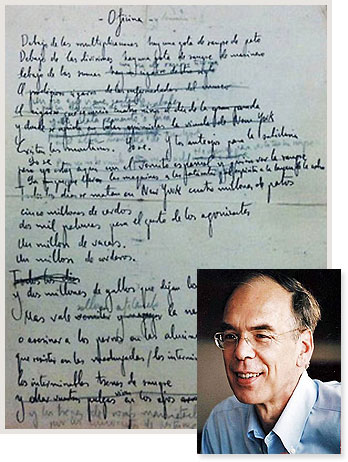

The discovery of the manuscript for "New York (Office and Denunciation)" by Christopher Maurer revealed some of García Lorca's telling revisions.

Photos: Manuscript courtesy of the Library of Congress Hans Moldenhauer Archive and Christopher Mauer, by Luis Fernandez-Cifuentes

Listen to Christopher Maurer discuss Federico García Lorca in New York and read from selected works in the New York Botanical Garden's Spanish Paradise audio tour.

While researching his forthcoming book on Spanish poet Federico García Lorca's residence in New York City (1929–1930), Professor of Spanish Christopher Maurer came across a poem manuscript he'd never heard of among the Library of Congress's online listings. Its location in an archive donated by music collector Hans Moldenhauer added to its intrigue.

It was the handwritten original, considered lost, for García Lorca's 1930 poem, "New York (Office and Denunciation)," from Poet in New York, first published in 1940, four years after García Lorca was assassinated at age 38 by Francisco Franco's soldiers. "Office and Denunciation" reflects García Lorca's aversion to New York's capitalist calculations and soul-sickness following the stock market crash. The manuscript includes nationalistic and messianic imagery omitted from the final version, such as the line, "I offer myself to be devoured by Spanish peasants," rewritten as, "I offer myself as food for the cows wrung dry..."

For Maurer, the manuscript's importance in illuminating the poet's process doesn't justify making it public domain. "How do you publish the unfinished works of a poet?" he muses. "Major, minor, it doesn't matter. It's like someone opening your desk drawer and saying, 'Hey, this is cool. Let's put it on the Web.'" Continued respect for an author's final decisions is crucial.

Maurer discovered that the manuscript had been a gift to poet José María Millares Sall, who, imprisoned by Franco and in financial need, sold it (through an American professor) at auction in New York, where Moldenhauer bought it. Millares Sall, who died in 2009, never spoke of it to anyone, even his family. They were shocked by the revelation. "Behind almost every manuscript," notes Maurer, "is a story of human drama." This fall, Maurer is giving a class focused on the treatment of manuscripts. "And how families keep their secrets," Maurer adds, "or share them."

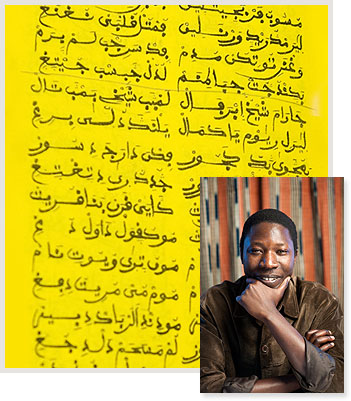

Fallou Ngom hopes Ajami manuscripts may help redefine literacy in many African countries.

Photos by Vernon Doucette

Listen to Fallou Ngom read from Kéba Dabo Cissé's poem on PRI's The World.

Read more about Fallou Ngom and Ajami in Bostonia.

Some families, indeed, are eager to dish. Not long ago, Associate Professor of Anthropology Fallou Ngom was in Senegal gathering documents in Ajami—the modified Arabic script that, since the tenth century, speakers of some twenty African languages, including Mandinka, have used to read and write—when he met a Mandinka man who shared manuscripts by his late father, Imam Kéba Dabo Cissé, a Qur'anic teacher.

Among these, Ngom found an unusual poem written during World War II—a curse calling for Hitler's demise, wishing that "he be betrayed by his own physician" and that his planes be destroyed, among other calamities. Ngom, who directs BU's African Language Program, explains that in Africanized Islam, long-standing local traditions have fused with Islam, and an imam may issue curses like any local elder.

From Senegambia to the Horn of Africa, millions use Ajami for everything from transactions to genealogies, prayers, and poetry. But when literacy rates are tallied, Ajami users are often discounted, in part because the script is not standardized, but also because of a persisting colonial stance that use of Latin script defines literacy. Cissé's is one of many documents attesting to the rich variety of cultural production in Ajami.

With a Guggenheim grant awarded in April, Ngom hopes to bring more Ajami scholars to Boston University. He and his students think different approaches, like using Ajami to educate rural villagers about such diseases as malaria, will make policy makers and scholars take notice. Ngom says he aims to publish a collection of original Ajami manuscripts like Cissé's to help ensure "that when we write about African history, cultures, and societies, we also incorporate these voices." ■

….This is not hell, but the street.

….This is not hell, but the street.Not death, but the fruit stand.

There is a world of tamed rivers and distances just beyond our grasp

in the cat's paw smashed by a car,

and I hear the earthworm's song

in the hearts of many girls.

Rust, fermentation, earth tremor.

You yourself are the earth as you drift in office numbers.

What shall I do now? Set the landscapes in order?

Order the loves that soon become photographs,

that soon become pieces of wood and mouthfuls of blood?

No, no: I denounce it all . . .

From "New York (Office and Denunciation)" by Federico García Lorca, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White, in García Lorca's Poet in New York.