|

|

||

|

|||

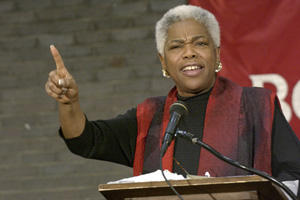

Former NAACP Legal Defense Fund president issues “call to conscience” in King’s memory

By David J. Craig

|

|

Elaine R. Jones Photo by Kalman Zabarsky |

|

Elaine R. Jones, the first woman to lead the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), knew from age eight that she wanted to be a lawyer. Her father was a Pullman porter in Virginia and a member of the nation’s earliest black trade union. Jones was the first black woman to enroll in, and graduate from, the University of Virginia School of Law. She turned down a job at a prestigious Wall Street law firm upon graduation to work for the LDF, where she defended death row inmates and was the counsel of record in Furman v. Georgia, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that abolished the death penalty in 37 states. Jones, who retired last year as LDF president and director-counsel, delivered an impassioned speech at the University’s 20th annnual commemoration of the life of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. (GRS’55, Hon.’59) on January 17. Following are excerpts.

Martin Luther King, Jr., who would have turned 76 this year, made profound personal sacrifices, Jones said:

Dr. King had four children, babies, and a wife and obligations. He never made much money. Dr. King was, in some sense, a reluctant warrior. He didn’t view himself as leader, rather as servant, so when the young minister was called to serve the people, he answered the call. The question he leaves for us is: when we are called, will we answer? The issues here with us are as real, as poignant, and as significant as the issues then.

King and other civil rights workers recognized the fundamental importance of voting, Jones said, and many died violently for promoting all Americans’ right to vote:

If our votes don’t count, or if our votes are suppressed, that goes to the core of this democratic system. Historically, African-Americans have had a very difficult time in this country securing and exercising the franchise. Martin made two great speeches, one of which was a “call to conscience” after the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, and it was about the right to vote. At the time, many African-Americans, and whites too, understood that struggle. Many [black] veterans had come back from fighting in World War II or Korea and got home to Alabama, Mississippi, or Georgia and said: what is this? These veterans stood on the front line, with the ministers and the others in our new movement. . . . If you go to the grave of [former NAACP president and Klu Klux Klan murder victim Vernon Dahmer] you’ll see on his tombstone: “If you don’t vote, you don’t count.” These were Martin’s soldiers. . . . and they have passed on the baton to us.

Lawyers play a crucial role in civil rights activism:

Thurgood Marshall once said to Martin on a march, “I don’t approve of these tactics, putting our children in harm’s way, being out here on the firing line. Women and children could face injury.” And Martin responded, “This is a massive non-violent peace movement. Anyone who is part of it is so because they want to be, not because there is a mandate.” And then he told Marshall, “You’re one of the country’s finest lawyers. I’m going to do what I have to do, and you do what you do best. Be the lawyer and come down and get us out of jail. That is your obligation.”

Thurgood, the first African-American on the Supreme Court and at one time the leader of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, took that advice seriously. Throughout the ’60s, that’s what the Legal Defense Fund did, represented all of the freedom riders and brought all of that litigation to the Supreme Court, trying to make equal justice under the law a reality for all people.

Our nation’s schools, Jones said, are failing minority children:

There is nothing more important right now than the issue of early childhood, elementary, and secondary education. We are not serving all of our children well. Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 broke the back of apartheid in the realm of public education. But we have dawdled. We cannot spend the next 50 years the way we spent the last 50. We have wasted time arguing and isolating school districts. We have to figure out what is stopping us from tapping in to the brainpower of all our kids. Most millionaires have their kids in public schools, but they’re public schools that they control, that they monitor, that they put the resources in. We want the same thing for all of our children.

![]()

21

January 2005

Boston University

Office of University Relations