|

|

||

|

|||

![]()

Art

for CyberArts’ sake

Festival, conference to explore public nature of digital art

By Tim Stoddard

|

|

|

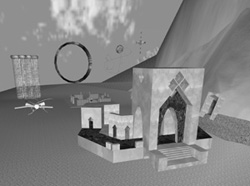

| At the first Boston CyberArts Festival, in 1999, BU’s Scientific Computing and Visualization Group (SCV) debuted the virtual reality experience Spirited Ruins. Since then, SCV has continued to refine the program, in which viewers explore the ruins of a mystical palace where inanimate objects are infused with life. Image courtesy of SCV. |

|

Is an MP3 downloaded from the Internet a piece of public art? Artists and critics have long debated what makes art public, but until recently that dialogue has neglected the realm of digital art, which now ranges from electronic music to digital animation to hypertext, virtual reality, and computer-generated visual art. If you log on to a virtual reality program online, is the experience any less public than looking at a statue in Boston’s Public Garden?

That will be a central question at a two-day conference on digital public art hosted by Boston University and other institutions during this year’s Boston CyberArts Festival. The conference, Digital Art and Public Space: Expanding Definitions of Public Art, is free and open to the public. It will take place on April 26 in the Photonics Center from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on April 27 at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum Auditorium at Harvard University from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Sponsored by the nonprofit arts organization Boston Cyberarts, Inc., the biennial festival runs from April 26 to May 11 and features a smorgasbord of performances, video presentations, educational programs, and exhibitions at locations around the city. As in previous festivals, in 1999 and 2001, BU faculty and staff will exhibit a number of digital arts pieces on campus during the 16-day festival.

The goal of the conference is to bring art administrators and curators together with practicing digital artists to explore such issues as the history, politics, and aesthetics of digital public art. “The finest minds in this field are coming together from all over the country to be on these panels,” says George Fifield, festival director. “This conference will give us a great opportunity to examine digital art through the lenses of public art and design. It’s the first conference of its kind ever.”

Ilona Lappo, assistant director of BU’s Center for Computational Science, and Laura Giannitrapani, manager of graphics consulting at the Office of Information Technology’s Scientific Computing and Visualization Group (SCV), helped organize the conference and will be among the panelists discussing such issues as whether the Internet is really a public medium. “Does the Internet enable us to make things public in a different way by transmitting them all over the world and making them available to anyone who can reach a computer?” Lappo asks. “It seems to me that it’s almost as public as going to the Public Garden.”

The conference is designed to initiate dialogue that will continue over the course of the festival. “We are going to point people to the various artworks available during the festival, some of which will fit the definition of public art and some will not,” Lappo says. “The idea is to stimulate their thinking, so that as they explore the rest of the festival, they’ll be able to evaluate the question of whether such a thing as digital public art is going on here as well.”

Palatable art

Fifield is surprised that the public dimensions of digital art haven’t

been discussed before now. Whether it’s light projected on a building

downtown or music piped into a park, digital art is often more palatable

to the public than traditional media. “Public art is a politically

fraught process,” he says, “and in many ways, digital public

art helps leapfrog over some of those issues because it’s temporary.

You can sometimes get away with things on a temporary basis that you couldn’t

if it were more permanent.”

Ricardo Benneto, director of the Urban Arts Institute at the Massachusetts College of Art and the principal organizer of the conference, says that new media also make it possible for curators to work with rising artists they wouldn’t have considered before. “The nice thing about temporary work is that it lets us work with younger artists who may not have the experience required for a major project that really changes the landscape on a permanent basis,” he says. “And the flexibility of digital technology makes that especially attractive.”

Real toads, imaginary gardens

BU has a long history of applying evolving technology to the arts. Through

its nonprofit educational venture High-Performance Computing in the Arts

(HiPArt), the SCV has been building partnerships with local artists to

bring their creations into virtual reality environments. With her SCV

colleagues, Giannitrapani has been working on several programs that immerse

viewers in rich three-dimensional virtual environments often based on

the drawings and paintings of artists from CFA and greater Boston. At

this year’s festival, she will present a new work entitled Terpsichore’s

Haunt, where visitors explore the abstract forms, spaces, and rhythms

created by dance. Standing in front of the SCV’s new Deep Vision

Display Wall (see B.U. Bridge, December 13, 2002), viewers wear 3-D glasses

and hold a navigational device to move through dance zones and inspect

three-dimensional animated forms and patterns that represent ballroom

dances such as the rumba, waltz, tango, and cha-cha.

|

|

|

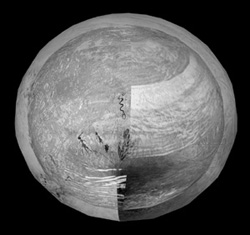

| A still frame captured from the virtual reality program Tracer. Courtesy of the SCV. |

|

“In these, I really want to capture the personality of the dance and the personality of the rhythm,” she says. As she was designing Terpsichore’s Haunt, Giannitrapani used her own experience as a dancer, translating her muscle memory into the sequence of animated forms. The result will be a new kind of digital experience. “In the past, we’ve certainly had dance projects where dancers use new technologies,” says Fifield “but we’ve never had virtual dancing like this.”

On May 9, audiences at the Tsai Performance Center can explore a different kind of virtual experience when the contemporary music ensemble Boston Musica Viva performs a multimedia piece entitled Tracer, by Richard Cornell, a CFA associate professor and chairman of the school of music’s music theory and composition department, with video by Deborah Cornell, a CFA assistant professor in the school of visual arts. The Cornells first composed Tracer as a virtual reality program run on the SCV’s ImmersaDesk, a giant screen 4 feet high and 10 feet long. Viewers enter a luminous revolving space with two concentric spheres, one slowly rotating around the other. The scenes and images that occasionally float into view were drawn from Deborah Cornell’s paintings and print works. Using a navigation wand, viewers draw lines on a virtual canvas in the center of the space, producing sounds whose timbre and pitch are a function of drawing speed and location in the spheres.

With the help of Giannitrapani and Robert Putnam at the Office of Information Technology, the Cornells captured a “fly-through” of the Tracer environment. “We edited together a 12-minute experience of the piece, which I’m now scoring with live instruments,” says Richard Cornell. “It’s a very complicated and rich experience. There are two concentric spheres, which represent a cosmic egg, or a world; inside you find evidence of human origin in the form of various language systems represented by human artifacts that have left tracings on earth. The idea is to talk about the impulse to draw, make lines, and leave tracings behind.”

For more information on the Boston CyberArts Festival, visit www.bostoncyberarts.org. For more details on the performance schedule of Terpsichore’s Haunt, visit http://scv.bu.edu/HiPArt. The detailed agenda for the conference Digital Art and Public Space: Expanding Definitions of Public Art is available at http://www.bostoncyberarts.org/daps.

![]()

18

April

2003

Boston University

Office of University Relations