|

|

||

|

|||

New center for probing memory and the brain

By Tim Stoddard

When George Bush the elder announced that the 1990s would be the Decade of the Brain, Boston University researchers had already been investigating that curious three-pound organ for many years. One area of interest common to CAS, ENG, and MED faculty has been the question of how our brains store and retrieve information, but until now those disparate efforts have been scattered among different laboratories. In an effort to better understand the biology of memory, an interdisciplinary team of CAS and ENG researchers has recently launched the Center for Memory and the Brain (CMB).

|

|

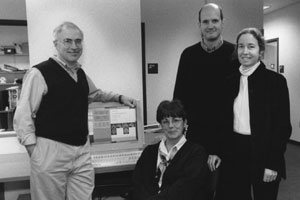

| Howard Eichenbaum, a UNI professor, a CAS professor of psychology, and director of BU’s Center for Memory and the Brain (from left), Denise Parisi, an administrator at the center, Mike Hasselmo, a CAS professor of psychology, and Chantal Stern, a CAS associate professor of psychology. Photo by Vernon Doucette | |

The goal of the center, says CMB director Howard Eichenbaum, a UNI professor

and a CAS professor of psychology, will be to bring together three fields

of memory-related research under one roof. While such research is not

new at BU, the interdisciplinary nature of the center will facilitate

new and improved collaborations between faculty with expertise in psychology,

neuroscience, and biomedical engineering.

With an administrative hub on the ground floor of 2 Cummington St., CMB

will feature a library, a seminar room, office space for visiting faculty,

and renovated laboratories on the second floor that will eventually extend

into the adjoining Life Sciences and Engineering building, which will

be built later this year. It will also include a state-of-the-art machine

for cellular imaging and new desktop PCs for modeling the interactions

between brain structures.

The four core faculty at CMB have been studying the problem of memory

from different angles. Eichenbaum’s focus has been on memory at

the level of neurons. His research involves trying to understand how rats

remember how to perform certain tasks in the laboratory. Using implanted

electrodes, Eichenbaum has been shedding light on how large groups of

neurons encode memories for such things as the correct route through a

maze. The advantage of working with rats is that a researcher can directly

study the activity of neurons. “The problem with rats,” Eichenbaum

says, “is that I can’t ask them if they remember what they

had for breakfast. My ability to carry on a discussion with them about

their memory is somewhat limited. I would like to relate my research to

what’s happening in humans, and the way to do that is to carry out

parallel studies in people that are inspired by studies in animals.”

Chantal Stern, a CAS associate professor of psychology, has been involved

in human studies of memory for several years. When working with people,

Stern uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to map the regions of

the brain involved in different kinds of memory. Her volunteers, mostly

healthy BU undergraduates, are asked to perform certain activities inside

the MRI machines at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Charlestown

facilities. In addition to studying young, healthy brains, she is using

this technique to better understand the cognitive changes that occur in

neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s,

and HIV.

“It’s important for my lab to work in collaboration with people

who are doing animal modeling,” Stern says, “because I can

then apply their information to how I design my human studies.”

Michael Hasselmo, another core member of CMB and a CAS professor of psychology,

has been collaborating with Stern, who is also his wife, on several projects

already. With Eichenbaum, Hasselmo has been studying the interactions

between neurons in the memory coding process. His research also probes

deeper into the brain, looking at the tiny spaces between neurons called

synapses. He and John White, an ENG associate professor of biomedical

engineering and the fourth member of the team, will continue at the new

center to do so-called “slice-physiology,” which involves

taking slices of animal brains and studying them in a petri dish to see

how the cells “talk to” one another.

“It’s very helpful to have people in these different topics

in close proximity to each other,” Hasselmo says. “People

doing imaging work come out of cognitive psychology and don’t know

much at all about individual neurons. And neuroscientists often don’t

know about the psychological concepts for cognitive function.”

CMB will not offer any degree-granting programs, Eichenbaum says, but

it will be an ideal environment for graduate students and postdoctoral

fellows to train in the neuroscience of memory. “We expect that

this center will be a terrific recruitment tool for bringing in students

who want to understand how memory works but who may not know exactly what

they want to do yet,” he says. “They’ll be encouraged

and supported to do collaborative work between laboratories, and so they’ll

get a better training in the global area of memory.”

Graduate students will come mainly from the CAS psychology department’s

brain, behavior, and cognition program and the biology department’s

neurobiology program. The center will also actively recruit undergraduates

into laboratory research through BU’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities

Program, student assistantships, and directed studies.

Along with doing rotations through the labs of the CMB faculty, graduate

students will be exposed to memory-related research from outside of BU.

Each semester, CMB will host two to four internationally recognized researchers

who will hold a series of seminars. This spring’s visiting scholar

will be Israeli neuroscientist Yadin Dudai, an expert in conditioned taste

aversion, a behavior in which humans and animals avoid certain foods that

previously made them sick.

As CMB gains momentum, it will add several new faculty hires in the coming

years. “Eventually, we hope to have up to eight people,” Eichenbaum

says. “But the idea is to keep the center’s faculty small

and the scope of its research very focused.” Over a longer period,

however, the breadth of research will eventually grow and may someday

include studies into how memory changes with aging.

![]()

10 January 2003

Boston University

Office of University Relations