|

|

||

|

|||

That

thing they did

Rock reincarnation: Boston band the Remains has its new day

By Brian Fitzgerald

In rock music, there are unexpected comebacks, and then there are Lazarus-like returns.

|

|

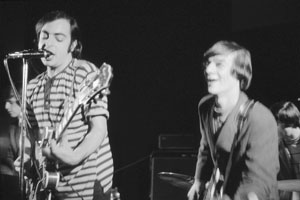

| Barry Tashian (left) and Vern Miller play a BU Union Forum concert with Junior Walker and the Shirelles on May 8, 1965. Photo by BU Photo Services | |

Fans of the rock group Boston, for example, rejoiced in 1986 after waiting

eight long years for the release of Third Stage, a follow-up album to

their classic Don’t Look Back. However, their level of patience

doesn’t compare to that of devotees of the Remains, who recently

celebrated the release of the band’s first album in 36 years.

Yes, that’s three-plus decades. Composed of four BU students, the

Remains were the hottest band in New England in the mid-’60s. They

played on the Ed Sullivan Show and Hullabaloo, and they opened for the

Beatles on their 1966 tour. They released an album, and seemed ready to

set the music world on fire. Then they did something really amazing.

They broke up. There is no short answer -- there never is -- when any

band disbands. Why, for example, did the Beatles break up? But the Fab

Four had already made an indelible mark on the music world. The Remains,

however, seemed to be on the verge of making it big. Asked if he would

have done anything differently if he could turn back the clock, bass player

Vernon Miller (SFA’69) says, “We were barely in our 20s and

faced with some pretty intense and fast growing up. Perhaps the group

breaking up was inevitable because that is what happened. I don’t

think any of us are presently kicking ourselves in the seat of our pants,

saying, what if and why didn’t I do this or that.”

Guitarist and singer Barry Tashian (CGS’65) says that business-wise,

it was not a sage decision to break up immediately following the Beatles

tour, but he doesn’t dwell on the past. “I often say, there

is no what if. Everything happens perfectly,” he says. “I

believe that if I had to do it again, it probably would have come out

the same.”

Miller, Tashian, and drummer Chip Damiani (SED’64) met at Myles

Standish Hall in the fall of 1963 and began jamming. They were joined

by keyboardist Bill Briggs (CGS’66) a year later, and started playing

in the Rathskeller in Kenmore Square. Pretty soon, during “Remains

nights” at the club (the present site of the new Hotel Commonwealth),

lines stretched around the corner, onto the bridge over the Massachusetts

Turnpike, and snaked all the way to Fenway Park. In fact, entertainment

mogul Don Law (CAS’68) heard the Remains at the “Rat”

and alerted music industry executives. Epic signed them after one audition.

Golden newies

Miller and Tashian look back on the music scene in Boston in the mid-’60s

with fondness, as WBZ radio gave much-coveted airtime to local bands such

the Remains, the Rockin’ Ramrods, and the Lost. The Remains were

a folk-rock band, drawing inspiration from blues masters Muddy Waters,

Johnny Lee Hooker, Little Walter, Otis Span, Sonny Boy Williamson, and

Elmore James and soul performers Otis Redding, Joe Tex, and Wilson Pickett.

The Remains gained a reputation as a loud, wild band, but they were also

tight and disciplined after much practice. In 1965 they took a one-year

leave of absence from BU and played the club and college circuit, in one

show at UMass sharing the stage with Bo Diddley and the Shirelles before

a crowd of 4,000. “The crowd size didn’t intimidate me,”

says Miller. “The Remains always seemed to have a let’s-go-get-’em

outlook on our performances. I think that was the first actual concert

we played. Up to that point it was clubs like the Rathskeller and frat

parties.”

In the studio, however, they were told to turn down their amps when recording

singles. “In a way we were frustrated,” says Tashian. “We

longed to blast away as we did on stage.” Miller says that recording

engineers and producers “were not at all used to recording loud

instruments with amps turned up about as far as they could go. They just

hadn’t done anything like that yet. It was impossible for us to

get our sound in a recording studio. I think that if we could have recorded

at the same volume we played on stage, then we could have realistically

captured the energy of the band.” Nonetheless, singles Why I Cry

and I Can’t Get Away from You got enough attention to gain an invite

to Ed Sullivan’s 1965 Christmas show, playing in front of 14 million

viewers. Then, in 1966, the Beatles came calling.

The four and the Four

“The Beatles tour was an incredible experience, and I am very grateful

for it,” says Miller. “It was both exciting and exhausting.

And it was extremely eye-opening. I think at first I was awe-struck. Standing

next to and hanging out with my idols -- such a cultural phenomenon and

force in music. The longer I spent with them and the more I saw them in

everyday life, I not only realized that they were just human beings, but

that they wanted to be just human beings. But they couldn’t even

walk down the street for a burger and a beer. In a sense, they became

prisoners of their own fame. Seeing something from the inside is often

extremely different than the way it appears on the outside. At this point

in their career, it was also evident that they were musically outgrowing

the confines of stage performance as it existed and wanted to explore

other musical directions, collectively and individually.”

|

|

|

| The Remains today: (from left) keyboardist Bill Briggs, singer-guitarist Barry Tashian, drummer Chip Damiani, and bass player Vern Miller. Photo courtesy of the Remains |

|

After the Beatles tour, the Remains did the unthinkable. They called

it quits. Miller, unlike the Remains’ fans at the time, wasn’t

convinced that the band was poised for rock stardom. “We didn’t

really have a drummer by then,” he says. “Chip Damiani had

left the group before the Beatles tour, and we hired N. D. Smart for the

tour. He is an outstanding drummer, but the band was no longer the same

four guys who used to set up in the basement of Myles Standish Hall and

play away. The Remains has always been one of those rare situations where

the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. When the four original

members sit down in a room and play music together, we always seem to

just pick up where we left off the last time.”

That’s just what the Remains did briefly in 1976 for six reunion

shows, and then again in 1998 when they played live in Spain and New York

City. Tashian has stayed in the music business since the original breakup,

recording with such country rockers as Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris.

The other members got jobs, but have also kept their musical fire burning.

Briggs still writes music, as does Miller, who also teaches it. And Damiani

has recently been drumming with bluesman Hilton Valentine. The Remains’

latest reunion, though, complete with Damiani -- and highlighted by a

September 27 performance at the Paradise Rock Club in Boston -- is especially

poignant because the tour is promoting their first new studio recording

in three dozen years. Their CD Movin’ On is being well received

by the rock media and is available at www.theremains.com.

Recalling the impetuousness of their youth, Miller and Tashian say the

band’s breakup was caused in part because of the restlessness of

the band members, and a let-down feeling after the rigors of the Beatles

tour. “I think the tour sort of scattered the band’s energies,”

says Tashian. “Chip had stepped out, so we had a new drummer, and

it was a bit difficult finding the old groove. Combine that with the fact

that we had never traveled so far and so fast before, and it was rather

disorienting. We hit 14 cities in 18 days. Today that doesn’t sound

like much, but in those days you had to charter a jet to do it.”

Miller agrees that the tour basically finished the first incarnation of

the Remains. “All the guys in the Remains are sensitive people,

and I think the tour took its toll on each of us,” he says. Still,

in spite of the decision to break up, he admits that “a side of

me was ready to dig in and see what we could do.” Now, 36 years

later, they are getting another chance to do just that.

|

![]()

1 November 2002

Boston University

Office of University Relations