|

|

||

|

|||

Visas

for Life

Holocaust exhibition reveals moral courage of diplomats

By Hope Green

Feng Shan Ho was born in China’s Hunan province, a place known for its hot-tempered warriors. Hiram Bingham was the son of a Connecticut politician. From opposite sides of the planet, they never met, yet as diplomats during World War II, both bravely used bureaucratic sleight-of-hand to rescue multitudes of people from the Holocaust.

|

|

| Prisoners line up at the concentration camp in Dachau, Germany, in 1938. | |

Accounts of Bingham and Ho’s morally courageous acts are among

the stories revealed in Visas for Life: The Righteous Diplomats, a traveling

exhibition installed at the 808 Gallery through November 6. The displays

tell of many diplomats who jeopardized their careers and sometimes their

lives to help Jews and other refugees escape Nazi-occupied countries.

An accompanying film and lecture series will be held in the College of

General Studies.

The events are part of an ongoing research and education initiative based

in San Francisco. Since 1994, Visas for Life founder and curator Eric

Saul has identified and documented more than 100 diplomats from 27 countries

who collectively rescued 250,000 people. He has amassed an extensive collection

of photos, videos, oral histories, and biographical materials, and the

resulting exhibition has toured the world.

Ho’s daughter, Manli Ho, spoke at an invitation-only opening reception

on September 19, and David Bingham, one of Hiram Bingham’s 11 children,

will visit BU on October 30 to join a panel discussion. Both have found

their involvement in Visas for Life inspirational.

“When we met other families of the diplomats,” Bingham says,

“we found they were from all different religious and ethnic backgrounds.

But when we talked about our fathers we found incredible kinship with

each other. Our fathers were caught in a moral dilemma and solved it by

falling back on principles that were remarkably similar in each case.

They all had the conviction they were doing the right thing.”

Israel has awarded Hiram Bingham and Feng Shan Ho, as well as other diplomats

Saul has identified, posthumous Righteous Among the Nations medals, one

of the country’s highest honors.

Escape from Vienna

Ho was named Chinese consul general in Vienna after Germany annexed Austria,

in 1938, and remained in the post until May 1940. Although the Nazis required

that Jews wanting to emigrate have a visa from the country they were going

to, most European countries and the United States had made it their policy

not to grant asylum to Jewish refugees.

|

|

|

|

Feng Shan Ho saved thousands of Jews in Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938 and 1939. |

|

Defying orders from his superiors, Ho issued thousands of visas to Shanghai,

China, knowing that Jews could use these documents to obtain transit visas

through nations such as Italy and Great Britain before finding their way

elsewhere. Some of the Viennese Jews did wind up in Shanghai, but most

resettled in North and South America, Palestine, the Philippines, and

Cuba.

“Diplomatic rescue is really fascinating,” Manli Ho says.

“These guys were all bureaucrats and they figured out these interesting

ways to allow people to escape by standing bureaucratic regulations on

their heads.”

Feng Shan Ho came to Saul’s attention in October 1997, when Manli,

a former Boston Globe reporter, wrote her father’s obituary. The

story got picked up by a wire service and appeared in newspapers around

the country.

Career sacrifice

Hiram Bingham was one of the few American diplomats to help rescue Holocaust

refugees. He was the U.S. vice consul in Marseilles, France, in 1940,

when the Germans invaded Paris. In collaboration with labor leader Frank

Bohn and Varian Fry, a volunteer with a grassroots rescue effort in the

United States, Bingham used his office to help save more than 2,500 people,

including painters Marc Chagall and Max Ernst, poet André Breton,

writer Heinrich Mann, and Nobel Prize–winning physiologist Otto

Meyerhof and his family. Bingham also helped organize a rescue network

with participants in the French resistance movement against Germany.

Bingham’s children learned of his heroism many years after his death,

when they found a box containing his journal and a stack of letters, photographs,

and documents in a locked closet behind his desk. The items revealed his

lifesaving activities during the war, and helped his children understand

why he had been passed over for promotions in the diplomatic service.

“The interesting thing to all of us in the family is that we had no idea he had done anything illegal,” David Bingham says. “He believed in honesty and truthfulness and in the importance not only of doing the right thing, but avoiding the appearance of doing something wrong.”

|

|

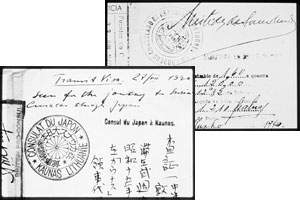

| Japanese and Portuguese visas are among the images on view. | |

Moral courage and personal choice are the overarching themes of the display

and related events at BU. The exhibition, lectures, and films are sponsored

by the greater Boston chapter of the American Jewish Committee, in association

with Boston University and Boston University Hillel. A companion display

called The Courage of Boston’s Children features award-winning essays

on courage written by students in Boston schools. Gallery tours and related

curriculum materials are available for middle and high school students.

Rabbi Joseph Polak, director of BU’s Hillel, believes Visas for

Life has powerful messages for young people.

“These consuls stayed up all night writing visas for thousands of

people waiting outside their embassies, until their rubber stamps wore

out and they had to order new ones,” he says. “Many of them

were humiliated or even lost their jobs when they went home. But they

saved 250,000 people. It has to do with moral heroism, and it’s

something that is certainly not in the forefront of student awareness

-- that from time to time it’s necessary to take risks for morality.”

Visas for Life: The Righteous Diplomats, will be on view at BU’s 808 Gallery, 808 Commonwealth Ave., through November 6. Gallery hours are Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., Saturday, noon to 6 p.m., and Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. For the schedule of related films and lectures, visit www.bu.edu/hillel/visas.shtml. For more information, call 617-457-8700.

![]()

20 September 2002

Boston University

Office of University Relations