|

|

||

|

|||

Data-gathering

space missions SPIDR satellite will map universe's cosmic web

By Brian Fitzgerald

How do galaxies form, evolve, and cluster with other galaxies? Hoping

to provide answers to these questions, this summer NASA chose the Center

for Space Physics' SPIDR satellite as the next mission in the agency's

Small Explorer (SMEX) program.

|

|

|

|

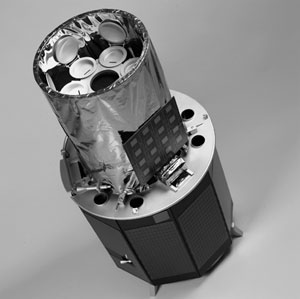

A model of the SPIDR satellite. Photo courtesy of Draper Lab |

|

"This is a major stepping-stone for us," says Supriya Chakrabarti,

director of the center, a CAS astronomy professor, and the principal investigator

for the $90 million project, which will be launched in 2005. This is the

largest research grant thus far in the University's history.

SPIDR, which stands for spectroscopy and photometry of the intergalactic

medium's diffuse radiation, will map the "cosmic web" of hot

gases that span the universe. Current cosmological theory holds that gases

produced by the Big Bang, which brought the universe into existence, condensed

into a giant filamentary web along which the galaxies and clusters of

galaxies eventually formed. SPIDR's findings will both test this basic

understanding of the nature of the universe and provide new information

to refine this understanding further.

SPIDR is one of two missions chosen by NASA from 46 proposals originally

submitted in February 2000. Chakrabarti says that the SMEX program's preference

for tightly focused, low-cost missions with small to midsized spacecraft

was a major reason that BU received the grant.

"NASA is seeking answers to major, fundamental, profoundquestions,"

he says. "We tried to figure out what was achievable given the available

funds, and we developed a plan that was feasible and low-risk." After

the list was pared down to seven proposals, the researchers wrote a concept

study report, which NASA reviewed. The space agency then sent some 20

experts to spend a day at each institution, scrutinizing different technical,

engineering, and management aspects of its program. Finally, Chakrabarti

and representatives from the six others under consideration traveled to

NASA in late June.

"We were each given 20 minutes to make our case," says Chakrabarti,

"and then, on July 2, NASA announced the selection of its next two

missions." The other mission, to be launched in 2006, is Hampton

University's Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere Explorer, which will determine

the causes of the highest altitude clouds in the earth's atmosphere.

A third of the SPIDR grant will enable BU scientists, who have overall

responsibility for the entire program, to design and build the six innovative

and sensitive ultraviolet spectrographs that will travel on board the

satellite. "Students will be involved in conducting mission and science

operations and performing data analysis," says Chakrabarti.

Roughly one meter wide and two meters long, the satellite will be launched

from the bottom of an airplane flown out of Vandenberg Air Force Base

in California and travel in an elliptical high earth orbit, using spectral

imagery to capture data on gases ranging in temperature from a few hundred

thousand to a million degrees.

The SPIDR project, which includes coinvestigators from eight other universities

and collaborators from Draper Lab in Cambridge, is planned to have a mission

lifetime of at least three years. "About one-third of the funds will

go to Draper to build a 'spacecraft bus,' which is a structure that houses

the electronics and provides pointing control, communicates with the mission

control, and has the necessary computing to carry out all essential tasks,"

says Chakrabarti. "The other third of the funds will go to a private

company, which will launch the satellite."

Members of the Center for Space Physics, including Tim Cook, a CAS research

assistant professor and the satellite mission instrument scientist, and

John Lapington, a research associate and the science payload manager,

will send commands to the satellite in space and gather data that should

answer fundamental questions concerning the formation and evolution of

galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and other large structures in the universe,

as well as address a number of questions related to hot gases in our own

galaxy.

According to the Big Bang theory, the universe started about 16 billion

years ago from an infinitesimally small point with infinitely large mass.

This point violently expanded, creating space, time, and everything else.

Some of this matter coalesced into stars and galaxies, although it is

thought that much of the matter that makes up the universe is unobserved.

"It must have gone somewhere," says Cook. "The question

is: where? Theorists think that the matter heated up and condensed into

these gas filaments." The SPIDR satellite is designed to detect and

measure these gases, which cannot be seen with the naked eye.

SPIDR isn't BU's first satellite - in 1999 the center's TERRIERS satellite

was launched to survey the earth's ionosphere and thermosphere in three

dimensions. However, because of a flaw in the pointing system built by

the center's industry partner, it wasn't able to orient itself so that

its solar panels fully faced the sun, and it ran out of battery power.

Only six SMEX missions have made it into space since 1992, five of which

are still operating and returning data. "From the time Explorer 1

was launched more than 40 years ago and discovered the Van Allen radiation

belts, Explorer satellites have made impressive discoveries by obtaining

significant science at the lowest cost," says Edward Weiler, NASA's

associate administrator for space science. SPIDR "will continue in

the Explorer tradition by investigating some of the most fundamental questions

raised in space science."

![]()

30 August 2002

Boston University

Office of University Relations