![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 3 December 1999 |

Vol. III, No. 16 |

Feature

Article

|

|

|

In 1947, Bradford Washburn

became the first man to climb Mt. McKinley twice.

He was accompanied by his wife, Barbara, the first

woman to climb the mountain, which is the tallest

in North America. Photo

by Thomas Winship

|

Mapmaker, photographer, and explorer of mountains' majesties celebrated at Mugar Library exhibition

By Brian Fitzgerald

What makes a mountaineer want to climb? Many think that these so-called peak-baggers have some kind of death wish. Sir Edmund Hillary famously scaled Mt. Everest "because it was there." But Bradford Washburn (Hon.'96), first sought out high altitudes because of his sneezing.

"I had terrible hay fever," explains Washburn at BU's Department of Special Collections on November 18. He was there to mark the opening of an exhibition entitled Bradford Washburn: Papers of the Eminent Cartographer, Explorer, and Photographer. The 89-year-old Washburn, known for his maps and photos of Mt. McKinley and Mt. Everest, began reaching for the sky in 1921 to get a bit of fresh air.

"When I was 11 years old I went to Squam Lake in New Hampshire, and I noticed that I didn't get hay fever when I went into the mountains," he says. "I climbed Mt. Washington that year with a cousin." A few years later, his father, dean of the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, went on a sabbatical to England. "My mother, my brother, and I joined him in Europe in the summer of 1926," he says. "We did a lot of good climbs in the French Alps. That got me really fascinated." He sold several articles on hiking to Youth's Companion magazine in his early teens, made his first Alpine climb at age 16 on Mont Blanc (15,780 feet), and published his first book, Among the Alps with Bradford, when he was 17.

Aerial photos as art

That book is part of the exhibition, along with

the tiny Kodak Brownie box camera his mother gave him when

he was 13, the same age he was when he took his first

airplane ride. He would spend the rest of his life building

upon these adolescent experiences, eventually earning wide

acclaim as a mountaineer, aerial photographer, and

cartographer. Washburn doesn't often discuss his photographs

in aesthetic terms, considering himself an explorer first.

But anyone who sees these photos of mountains and glaciers

immediately notices the abstract beauty of the intricate

patterns of rock, snow, and ice. In 1929 he won the

Appalachian Mountain Club photography competition for his

Sunrise, Aiguille du Midi, a photo of a rock peak in

Chamonix, France.

|

|

|

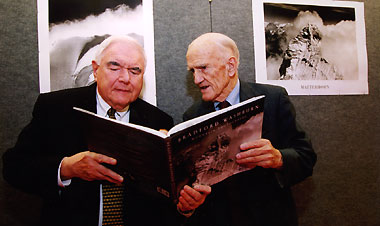

Department of Special

Collections Director Howard Gotlieb (left) and

Bradford Washburn take a look at Washburn's new

book, Bradford Washburn: Mountain Photography,

during the November 18 reception marking the

opening of an exhibition of Washburn's papers at

Mugar Memorial Library. Photo by Bethany Versoy

|

In fact, Washburn climbed mountains in Alaska with a team that had long experience in exploration and survival in freezing temperatures. During World War II he served as a consultant to the U.S. armed forces, reevaluating all American equipment for Arctic and sub-Arctic warfare. "In 1941 the U.S. was completely unequipped for this type of battle condition," he says. "It had gear from World War I. When the new equipment was developed by the summer, they couldn't wait six months for the winter to test it. So we went to Alaska."

In the Jack-and-Jill tradition

In 1942 Washburn took part in his first ascent of

Alaska's Mt. McKinley (20,320 feet). It had been climbed

only twice before, in 1913 and 1932. Five years later he

became the first person to complete two ascents of Mt.

McKinley. Washburn's climbing partner on the later

expedition was his wife, Barbara (Hon.'96), the first woman

to climb North America's highest peak. Shown in a photo from

the exhibition (above), they are told that they look fairly

cheerful on a mountain that is sometimes whipped by 100-plus

mile-an-hour winds and chilled with 70-below-zero

temperatures. "Oh, that photo was taken in June," says

Washburn, "when the weather is the best, and it was at only

10,000 feet."

"The climb from 18,000 feet was relatively easy," says Barbara, who was also at the opening of the exhibition. "We had a comfortable camp and had been on the mountain for two months and were acclimatized."

Mountain climbing is no longer just a man's sport. Do today's women climbers ever contact Barbara? "Once in a while," she says. "A few years ago a newspaper reporter called me from Anchorage, Alaska. He said, 'A girl has just soloed Mt. McKinley. What do you think?' The first answer that came into my head was, 'Oh, the poor thing, she missed all the fun.' He asked me what I meant. Well, for me the best part of the trip was sitting around the stove every night having good conversation. Marching up the mountain out of breath and tired -- that was hard. It was the companionship that made it worthwhile."

The Washburns' climbing days are mostly over -- Bradford is busy at Boston's Museum of Science, where he was named director in 1939. In 1980 he was named director of the museum's corporation, and in 1985, was named honorary director for life. Two years ago, however, he did "christen" a climbing wall after a dedication ceremony at Milton Academy. "The kids said half-jokingly to Brad, 'Why don't you climb it?' Well, he surprised them," says Barbara. Washburn, at the ripe young age of 87, scampered right to the top.