![]()

Departments

![]()

|

27 August 1999 |

Vol. III, No. 4 |

Feature Article

A Boy's Willa

By Eric McHenry

"Will you tell me who Willa Sibert Cather is?" Robert Frost wrote to Louis Untermeyer on January 7, 1916. "Is the name a man's? That's what I particularly want to know. Is he (or she) some poet I ought to have read?"

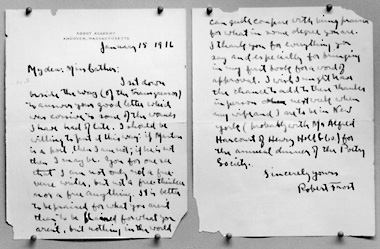

This curious letter isn't lent much context by other correspondence in the book that documents Frost's lifelong friendship with Untermeyer. Nor is it properly framed by anything in the Selected Letters of Robert Frost, or, for that matter, any of the extant writings about novelist Willa Cather. To make an educated guess at why Cather's identity, and "particularly" her gender, were at that moment matters of such urgency to Frost, one must visit the Theodore Roosevelt Room on the first floor of Mugar Memorial Library. There, in a showcase full of items from the extensive Frost holdings of Special Collections, hangs a letter the poet wrote only eight days later.

"My dear Miss Cather . . ."

|

|

Old letters from venerable pens are often multiply encrypted -- by literal fading and fading from context, by the unfamiliar syntactic conventions of the past, and by the idiosyncratic word choices and penstrokes common to so many geniuses. Frost's letters of nearly a century ago, however, are like his poetry -- not a jot of their intellectual substance is compromised by their directness.

"I should be willing to put it this way," Frost wrote to Cather. "If Masters is a poet, then I am not; if he is not then I may be. You for one see that I am not only not a free-verse writer, but not a free-thinker nor a free anything. It is better to be praised for what you aren't than to be blamed for what you aren't, but nothing in the world can quite compare with being praised for what in some degree you are."

Here, drawing a bright line between his work and that of Edgar Lee Masters, Frost foreshadowed his pronouncement of years later that writing free verse is like playing "tennis with the net down." He also set the tone for a sustained mutual literary admiration. "Willa Cather is our great novelist now," Frost would write to John Bartlett in 1926. Likewise, in Willa Cather: A Literary Life, James Woodress reports that Frost was "just about the only contemporary poet [Cather] did like."

The Robert Frost Collection was donated to BU by Paul C. Richards (CAS'60, Hon'82), one of the most generous benefactors of Special Collections. Comprising manuscript versions of more than 60 poems, some of which are unpublished, more than 100 letters, and rare photographs and first editions, it is among the country's most comprehensive Frost archives.

At the moment, visitors to the Roosevelt Room can also see original documents in the hands of Henry VIII and George Washington, private correspondence of Abraham Lincoln and of Walt Whitman, and hand-annotated portfolios of music from the Ella Fitzgerald and Cab Calloway collections, to name just a few.

"The material in there rotates," says Perry Barton, exhibitions coordinator for Special Collections. "We collect in such a wide range of genres, and over the past couple of years we've tried to create a changing exhibition that helps people know what Special Collections is. We think of it as an educational tool."

"Case Studies" is an occasional feature highlighting items of interest from the University's collections and archives.