![]()

Departments

![]()

|

Week of 9 October 1998 |

Vol. II, No. 9 |

Feature

Article

The heart of the matter

At 50, a definitive epidemiologic study looks ahead

By Eric McHenry

Acute indigestion is a common cause of death. Freckles can mean a predisposition for heart disease -- an ailment to which women are generally not susceptible. Exercise is bad for you.

Prominent members of the medical community were making such pronouncements just 50 years ago, when the Framingham Heart Study began. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the nation's number one killer, but science had little more than a collection of hunches as to what caused it, how it operated, and how it could be treated. Some were better than others.

"There were cardiologists who felt that obesity and hypertension might be important," says William Kannel, MED professor and senior investigator for the Framingham study. "Some felt that diabetes should be looked at. One of our doctors thought that having freckles was a sign that you were predisposed! Almost no one thought that physical activity was good for you. In fact, doctors were advising their patients to avoid it at all costs if they had the slightest suspicion of a present heart disease."

Today, doctors know that inactivity primes the body for heart failure; they know that high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol increase the likelihood of heart attack; they know that smoking, obesity, and diabetes are all directly linked to incidence of CVD. And for that knowledge they are perhaps more indebted to the Framingham study than to any other single source of information.

|

|

|

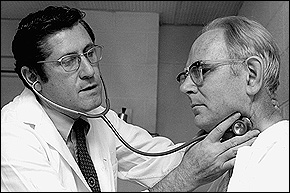

William Kannel examines a

patient from the Framingham Heart Study's first

generation of participants. Kannel has been with

the study since 1949, serving as its director from

1966 to 1979. Photo

courtesy of William Kannel

|

Widely regarded as the definitive epidemiologic study of the century, Framingham has held fast for 50 years to a simple method and objective: biennial examinations of an adult population to determine the ways in which lifestyle, environment, preexisting conditions, heredity, and other factors contribute to CVD. In 1948, under the sponsorship of the National Institutes of Health's National Heart Institute (now the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), researchers began looking at and questioning about 5,000 healthy adult residents of Framingham, Mass., about 20 miles west of Boston.

"Framingham was the first major study to apply an epidemiologic approach to seeking out the causes of cardiovascular disease on a population basis," says Kannel, who has been with the study 49 of its 50 years and who served as its director from 1966 to 1979. "We were trying to determine in what particulars those who go on to develop cardiovascular disease -- heart attacks, strokes, heart failure -- differ from those who go on without it to advanced age. Since nobody had a really good idea what was promoting the disease at that time, we were looking at lifestyles and personal attributes that theoretically might be relevant."

In 1971 investigators added another cycle of about 5,000 participants to the study -- a literal second generation, comprising the sons, daughters, and sons- and daughters-in-law of the first group; these younger subjects have been examined only once every four years, although that is about to change. "Things are just happening so quickly in the field," says Ralph D'Agostino, CAS professor of mathematics and director of statistical analysis for the study. "There's no longer the luxury of waiting four years between examinations. For several decades, Framingham was pretty much the only game in town in terms of cardiovascular research. So researchers could collect their data, process it in a very deliberative manner, and whatever they came up with was extremely important and unknown." The advent of competing studies and the explosion of new medical technologies have heightened Framingham's need both for faster output and for more rapid assessment of these technologies, D'Agostino says.

The study's first- and second-generation participants have shown impressive fidelity. Less than 5 percent have dropped out -- an unusually high retention level, even for a project that offers free medical diagnoses to its volunteers. D'Agostino adds that a third generation will likely sign on in the near future, providing additional information for those studying the role of heredity in heart disease.

Vital signs

In the late 1960s, Kannel recalls, the fiscally strapped

National Institutes of Health withdrew funding from the

study, which government officials believed to be at the end

of its productive life. At that point. Thomas Dawber,

original architect and erstwhile director of the project,

brought it to the Boston University School of Medicine,

where he was chair of the department of preventive medicine

and epidemiology.

"He decided to find outside funding from foundations and the pharmaceutical industry," says Kannel. "And in that four-year hiatus when the NIH had bowed out -- when they said there was nothing more to be learned -- the study produced 48 publications in major medical journals." The NIH subsequently reassumed its sponsoring role, and the study has since operated under the joint auspices of the NHLBI and BU. Philip Wolf, MED professor of neurology and preventive medicine, is the current principal investigator.

After its first 10 years, the study began delivering breakthrough discoveries with remarkable consistency. In 1960, it published convincing evidence that smoking increased the risk of coronary disease; cigarettes were responsible for more heart attacks, researchers pointed out, than cases of lung cancer. These findings provided the foundation for the first definitive surgeon general's report on smoking, which prompted the federal campaign against cigarettes in the 1960s.

Study results also confirmed that high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, physical inactivity, obesity, diabetes, menopause, and an array of other conditions promoted CVD. "The study corrected a lot of misconceptions about the so-called risk factors for heart disease," says Kannel. "In fact, the term risk factors was coined by Framingham investigators."

Slow on the uptake

There has been initial resistance to many of the study's

findings -- from the American Medical Association, from the

American Heart Association, and from cardiologists and

physicians generally. New information about high blood

pressure, Kannel says, met with a particularly refractory

medical community.

"People are never eager to abandon what they've learned in medical school," he says. "Many, many doctors were taught that the evil consequences of hypertension derived from the diastolic component of blood pressure; they were taught that women tolerate hypertension well; they were taught that casual office blood-pressure readings were not reliable and predictive.

"We were able to test these clinical impressions," he says, "and to prove many of them wrong. But getting people to give them up was another matter. It took us 20 years to get physicians to pay more attention to systolic blood pressure."

If the medical community has been slow to budge, the general public has been at times immobile -- literally. Americans, even those participating in the study, seem to have heard but not heeded its warnings about obesity and the importance of exercise. Richard Myers, MED professor of neurology and supervisor of the study's genetic analysis component, believes television to be the reason. It arrived on the scene almost at the same time as the study, and the two seem to have been lifelong competitors.

"Television watching correlates quite strongly with weight gain," says Myers. "It's just amazing how strongly linked the two are for all age groups, although you really see it in children. Habits and lifestyles are established early, and people find them difficult to break."

Coming around

Not all of the study's reports, however, have found a

nonresponsive audience. According to a recent issue of U.S.

News and World Report, Framingham findings are credited with

contributing to a dramatic decline in the death rate from

heart disease. In 1996 there were 87 cases of CVD for every

100,000 Americans -- down from 220 in 1963. The smoking rate

among men has decreased by about three-fifths since 1948,

and drugs have been developed to regulate blood pressure and

cholesterol.

And as technological advances make epidemiology a more precise enterprise, the study's efficacy increases. The Human Genome Project, which will soon produce a comprehensive map of all human genetic material, opens new frontiers for Framingham. It has long been believed, Myers points out, that genes play a role in determining who gets heart disease.

"What's changed over the last several years," he says, "is that we've acquired the capability to locate those genes that might be responsible for disease expression. Improved technology permits us to ask questions that we couldn't ask before."