Our Radical Year

President Robert A. Brown

Joining the AAU

What Price, Innovation?

Ruha Benjamin

Discovery Junkies

William Saturno

Dark End of the Spectrum

Helen Tager-Flusberg

Human Engineers

Dean Kenneth Lutchen

Unlocking Words

Abriella Stone

Cavewoman Walking

Jeremy DeSilva

The Politics of Listening

Ashish Premkumar

$1B Campaign

Stepping Up

Dean Maureen O’Rourke

Professor in the Coal Mine

Lucy Hutyra

Teaming up with edX

Clapping, Stomping, Twirling

Sajan Patel

Force Field

Sally Starr

The Computer Will See You Now

Dr. Brian Jack

Birth of an Artist

Jim Petosa

Elizabethan Time Machine

Diana Griffin

Joining the Patriot League

Healing Zambia

Donald Thea

Spring Break, Not

Jenne Bougouneau

Our Smartest Class

Creaky Nation

Julie Keysor

Melting Prison Bars

André de Quadros

Best of Both Worlds

Katie Matthews

Faculty Accolades

Film Frisson

Mary Jane Doherty

Financials

Saliva Solution

Eva Helmerhorst

Testing Fate

Catharine Wang

Our Radical Year

President Robert A. Brown

Joining the AAU

What Price, Innovation?

Ruha Benjamin

Discovery Junkies

William Saturno

Dark End of the Spectrum

Helen Tager-Flusberg

Human Engineers

Dean Kenneth Lutchen

Unlocking Words

Abriella Stone

Cavewoman Walking

Jeremy DeSilva

The Politics of Listening

Ashish Premkumar

$1B Campaign

Stepping Up

Dean Maureen O’Rourke

Professor in the Coal Mine

Lucy Hutyra

Teaming up with edX

Clapping, Stomping, Twirling

Sajan Patel

Force Field

Sally Starr

The Computer Will See You Now

Dr. Brian Jack

Birth of an Artist

Jim Petosa

Elizabethan Time Machine

Diana Griffin

Joining the Patriot League

Healing Zambia

Donald Thea

Spring Break, Not

Jenne Bougouneau

Our Smartest Class

Creaky Nation

Julie Keysor

Melting Prison Bars

André de Quadros

Best of Both Worlds

Katie Matthews

Faculty Accolades

Film Frisson

Mary Jane Doherty

Financials

Saliva Solution

Eva Helmerhorst

Testing Fate

Catharine Wang

Cavewoman Walking

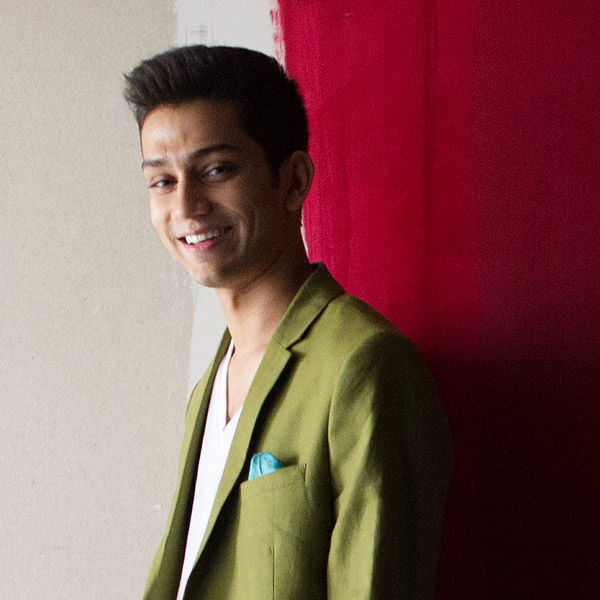

Anthropologist Jeremy DeSilva reveals how early humans really went mobile.

close video

As an upright human being, Jeremy DeSilva feels an irresistible pull to tell the stories of our ancestors’ bones. Ancient ones, in particular. “I’m completely hooked on bringing these things back to life. I see the bones they have left as this incredible gift, a very rare window into reconstructing the way things used to be.”

The assistant professor of biological anthropology is fascinated with the way early humans moved, whether in trees or on the ground. After studying the skeleton of a two-million-year-old female belonging to the newly discovered Australopithecus sediba species, DeSilva encountered an odd story. In this single pre-human being, he saw what resembled a chimp-like foot and torso along with modern-looking hands and humanlike pelvis and spine. Up to this point, DeSilva, like all anthropologists, believed humans came down from the trees once they started walking upright. He was now knee-deep in a mystery.

“These were all individuals. They all ate, breathed, lived, had babies. When I’m working with these fossils, I feel a real connection to them.”

But it wasn’t until he teamed up with BU Physical Therapy Associate Professor Kenneth Holt (SAR’83) that the clouds would start parting. From looking at the pelvis, Holt determined that the creature walked upright. The two scientists hypothesized that she strode with a gait that in modern humans is called hyperpronation, displaying an evolutionary progression uniquely adapted to both walking and climbing.

In April 2013, Holt and DeSilva detailed their research in Science magazine. The story was quickly picked up by journals and media outlets around the world, including National Geographic, BBC News, USA Today, and the Boston Globe. That well-known evolutionary chart illustrating man’s tidy progression from four-legged to upright was upended.

“Every single fossil that gets found, even the tiny little scraps, are telling us something, and it’s our obligation to tell that story.”